Following the January 1982 assassination of the Turkish Consul in Los Angeles, a Turkish import shop owner and honorary diplomat’s shop in Cambridge was bombed. The Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide claimed credit for both, issuing a demand: Pay attention. This is the second in a four-part series on the killing of Orhan Gündüz, a low-level Turkish diplomat living in the Boston area caught up in an international assassination ring. Read chapter 1, chapter 3 and chapter 4.

On April 23, one day before Armenian Martyrs’ Day, protesters descended upon the reopened Tokpaki Imports. The store was still recovering from the blast that tore through the shop a month before, and proprietor Orhan Gündüz could only watch as 15 picketers gathered outside.

Martyr’s Day was the annual commemoration of the beginning of the Armenian genocide, and Orhan had become a locus for the protesters’ discontent over the lack of recognition of the atrocities two generations prior. The global commemoration offered the Justice Commandos a once-a-year spotlight to finish what they had started. An FBI surveillance team was also watching and snapping demonstrators’ photos, hoping for fresh leads.

Surveilling the protest and wiretapping Orhan’s home phone were the FBI’s logical next moves. What had been the Bureau’s most promising lead — a tip about a stripper bound for Arizona with a duffle bag full of dynamite — revealed itself as a jealous suitor’s hyperbolic tale.

A local prisoner also claimed an Armenian woman sold him a gun from the Combat Zone, Boston’s Red Light district. He said they were due to meet the night of the bombing but she mysteriously flaked. That lead also went nowhere.

Each dead end wasted time. And as the hunt for suspects stalled, the FBI started fielding requests for Orhan’s protection — from Orhan himself, the local police, another foreign diplomat and even his Congressional representative.

Orhan kept a shotgun at his store but insisted it was no use against a trained assassin.

“He feared for his life,” Barry Hoffman, Orhan’s friend and New England’s Pakistani Consul General in New England, later told the New York Times. “He said to me, ‘Look, I’m a shopkeeper and a diplomat. I’m not a gunfighter.’”

U.S. Rep. Barney Frank had written to the FBI asking that they protect Gündüz shortly after the bombing and still awaited a response.

On April 24, the FBI surveilled the demonstration at Boston’s Government Center commemorating the genocide’s anniversary. Orhan made it through the volatile date unscathed.

Two days later, Charles P. Monroe, the FBI’s assistant director of its Criminal Investigative Division, responded to Frank’s request, passing responsibility for Gündüz’s protection over to the State Department.

Despite the threats and intercessions on his behalf, Orhan was not offered direct protection from the FBI, State Department or anyone else. The Cambridge Police Department did allow him to park his car in its garage temporarily.

Orhan remained an easy, unprotected target.

A mile from his shop, at least one JCAG operative was busy getting to know Somerville.

A united front

The FBI used photos from the shop protest and demonstration on April 24 to identify and interview Boston’s Armenian community, inquiring about the bombing and individual views on Armenian terrorist activities. The Armenian-American community at large did not approve of the violence or the tactics used by JCAG, instead favoring political advocacy and activism focused on national and state-wide genocide recognition. But that didn’t mean they believed that Turkish officials were entirely without fault, complicit in a policy that denied the genocide.

“All made it quite clear,” wrote one of the agents, “that whether they did or did not condone Armenian terrorist activities, the Turks deserve to suffer the consequences of their atrocities against the Armenians.”

From young to old, hostility toward the Turkish government was a unifying element in a diaspora otherwise split between two dominant political affiliations and churches. No one stood out as singularly dangerous, but there were divisions. In Watertown, a leader at St. James Church all but pointed the finger at the rival church St. Stephen’s and noted his own opposition to violence, which had earned him threats. He also told the FBI of a distinct difference between the congregations — St. Stephens included “more militant, radical Armenians,” a group “made up in part with those younger Armenian emigres from Beirut, Lebanon.”

The two men accused of killing the Turkish Consul Kemal Arikan in Los Angeles two months before, Hampig “Harry” Sassounian and Krikor Saliba, came from that same “militant” background. Arikan had allegedly given a public interview in which he denied the genocide had occurred, further attracting the ire of JCAG.

The FBI ran into the same brick wall that stymied them in Watertown when they tried to speak with Sassounian, a 19-year-old Lebanese-Armenian. Saliba remained at large, and the FBI believed he likely had escaped the country entirely.

A search of Sassounian’s car revealed tapes of Kenny Rogers’ “Greatest Hits,” Dimimitris Mitropanos’ “Erotikia Laika” and Rush’s “Moving Pictures,” Jovan’s “Sex Appeal for Men” cologne, Italian sunglasses, Marlboros and a pair of Smith & Wesson handcuffs. In his house, agents found photos of Sassounian wielding guns and what they described as a manifesto from the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF). It is not included in the files.

The FBI explored the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF,) a youth arm of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), as a recruiting point for the Justice Commandos but found nothing conclusive.

For months, Orhan had persevered in the face of threats that escalated to violence. The Boston Herald later reported that less than an hour before his death, he promised friends that he would not return to his shop without increased protection.

Mr. ‘Loosciano’ and the Rabbit

On April 29, 1982, around 1:30 p.m., a South Boston woman received a call from a man who had seen her advertisement in the Bargain Hunter’s Guide, a classifieds magazine available at local grocery stores. The caller was interested in purchasing the turquoise 1976 Volkswagen Rabbit hatchback she had listed for sale.

She told him it was still available, but she had a flight to Florida to catch with her 12-year-old son.

The man said he was close-by — just in Harvard Square — and could be right over. She provided her address.

Soon after, a young white male, about 5 foot 6, 130 to 140 pounds with black, soft, curly hair —professionally cut and groomed short — arrived at her house in a taxi. To the Rabbit’s owner, the man looked maybe in his late twenties “with delicate features, a smooth complexion and a small nose.” He wore blue designer dungarees, ankle-length brown leather boots and sunglasses.

The young man gave the surname, Luciano, noting that he was Italian. He had a foreign accent, but not one the woman thought resembled Italian. Though skeptical, she continued with the transaction. The man said he wanted her ‘76 Rabbit as one of 30 cars he was hoping to acquire for his father’s used car business in Memphis. They discussed the vehicle’s condition and price.

According to Road & Track Magazine, the 1976 Rabbit performed well, was relatively fuel-efficient and “great fun to drive,” though not the most reliable. It was the opposite of imposing — a bright, quirky car perfect for the city. As they talked, the Rabbit’s owner noticed Mr. Luciano shifting back and forth. The man was playing with his sunglasses and his multicolored ski cap — an odd choice on a relatively warm day —and folding his arms in front of him, as if he were extremely nervous. She thought she smelled alcohol on his breath but didn’t want to miss her plane by delaying.

After she knocked $100 off for the body damage Mr. Luciano pointed out, they settled on $1,900. He had a wad of cash on hand, but she could only take a cashier’s check because she was going out of town. Mr. Luciano then went to the closest bank, Mount Washington Cooperative Bank in South Boston.

A 19-year-old bank teller assisted him upon entering. Her description of him later generally matched the earlier one: 25 to 35 years old, five foot seven, wind-blown brown hair and a medium complexion. She didn’t think he was local to Southie and noted that he didn’t speak with a typical Boston accent. He gave her 19 hundred dollar bills for the check.

Mr. Luciano returned to the house and told the Rabbit’s owner to sign the title over to “Loosciano Used Auto Yard, Memphis, Tennessee.”

She took note of the odd spelling of the name L-o-o-s-c-i-a-n-o. It sounded phony and added to her doubts about him actually being Italian. Mr. Loosciano said he would pick up the car later. He shook hands and wished her luck before getting into a cab.

When the Rabbit’s owner departed for Logan Airport, she assumed she would never see her old car or Mr. Loosciano — or whatever his name actually was — ever again.

May 4, 1982: ‘Nice day for jogging’

JCAG operatives continued to prepare for something as the FBI chased down one fruitless lead after the next related to the bombing of Topkapi Imports. Disparate authorities struggled to make progress in the face of a unified front. The local Armenian community didn’t have intel — or wasn’t talking, and neither was the one presumed-JCAG assassin they had apprehended in LA. There was a perceptible ticking clock, but only a few knew when time would run out.

On the morning of the last day of his life, Orhan Gündüz took in the sea air from his Nahant home. He had stayed close to water much of his life, having grown up along the Bosphorus, and now enjoyed evening swims and days at the beach with his young son, Doğan.

He walked down to the end of his driveway to pick up the trash knocked over by his dog, the German Shepherd he had obtained to help keep his family safe amid the increasing danger.

“Isn’t it a lovely day, Mr. Gündüz?” a neighbor asked. It was breezy and clear in the 50s; not too hot, not too cold for May.

“Yes, isn’t it?” Orhan said before departing for work at his Cambridge store.

7:30 a.m.

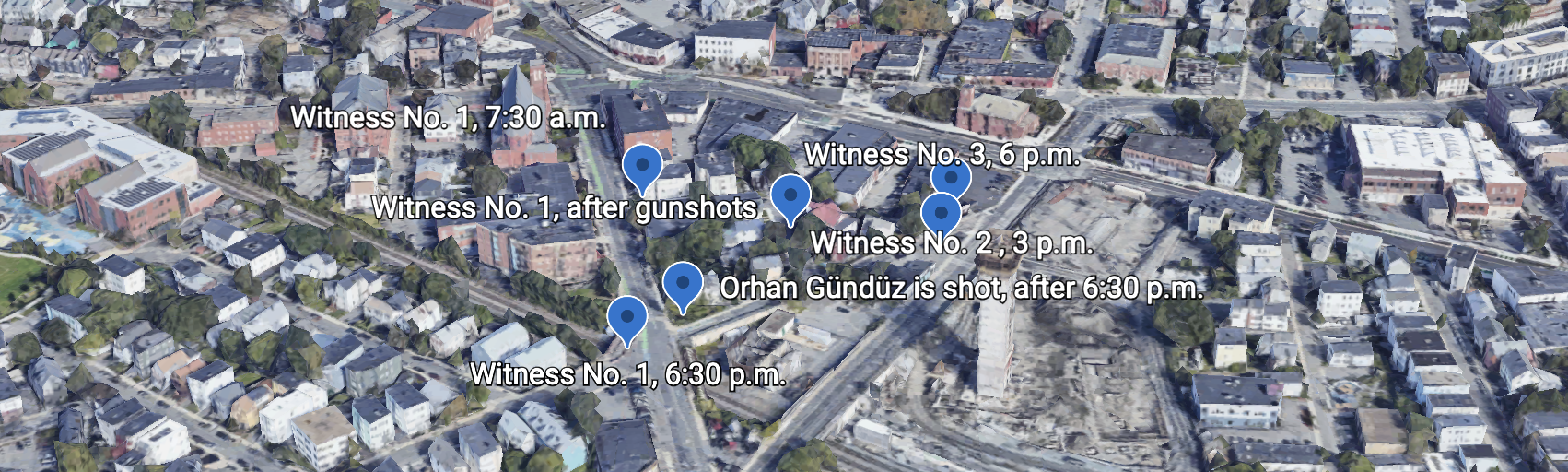

Ten miles away from Orhan, a Somerville boy, Witness No. 1, was waking up for school. Perennially tardy, the boy had been warned that to return to school, his widowed mother had to accompany him and speak to the counselor.

Instead of preparing for the parent-teacher meeting, Witness No. 1 made himself a full pancake breakfast before heading out alone on rollerskates. As he careened down Webster Avenue into Union Square, Somerville, he spotted two young men.

They seemed out of place, perhaps a little too flashy against the muted backdrop of the working-class neighborhood. Both wore jogging suits — one royal blue with stripes and the other brown with stripes — sneakers of the Adidas-and-or-Nike varieties and aviator sunglasses.

“Nice day for jogging,” said the boy as he roller-skated by. It was a break from the unseasonably warm weather Boston had experienced lately.

“Yeah,” answered the shorter of the two men. His skin was broken out with pimples as if he had just shaved a beard. The roller skater noticed the pack of Camel cigarettes hanging outside of the jogger’s pocket. The other jogger sported a thin black mustache and more tanned complexion, clearer “in respect to the pimples,” Witness No. 1 noted.

After getting to school, the boy’s counselor sent him back home because he had neglected to bring his mother.

8:45 a.m.

Witness No. 1 chatted with friends in the hallway before he roller-skated back along Central Street, turning from Avon to Summer Street and then riding through Union Square, spotting the pair again at the corner of Webster Avenue and Everett Street.

1 p.m.

While he was home for the day, Witness No. 1 saw the same young men jogging around Union Square several times in the afternoon. They were both wearing driving gloves. They might have been training for something, but it wasn’t the Boston Marathon, which had occurred a few weeks before with temperatures so hot the two-man race to the finish was called “Duel in the Sun,” with famed runner Alberto Salazar prevailing.

3 p.m.

A woman, Witness No. 2, entered the Union Square Dunkin’ Donuts, ordered the usual and took a seat at the counter by the register. The orange-tinged interiors and wall of windows made it the perfect spot to people-watch in Union Square. It was also a favorite of Somerville cops who needed a quick fix while still keeping the city’s police headquarters in full view across the square’s main drag.

After about five minutes, a young man — approximately 19 or 20, 5 foot 6 and 140ish pounds — in a blue tracksuit sitting next to her turned to face her.

“Do you have any pot?” he asked.

Taken aback, Witness No. 2 said “no” and got up to leave. It was a strange encounter, even for the motley crew that sometimes hung around Union Square.

Around 6:30 p.m.

Photo by Gabriella Gage

The jogger might have had better luck had he asked Witness No. 3, who had spent the day with a “buzz on” after smoking a little marijuana. Just after 6 p.m., she had come off the high and was standing at the auto body shop at the corner of Newton and Prospect Streets, outside Union Square, when a young guy wearing a blue jogging suit caught her eye.

She thought she recognized him as someone she knew from the Roosevelt Towers, a housing development just over the Cambridge line, where she often visited her cousin. The cousin had told her that the young man was “dangerous,” “kills people” and to “stay away from him.” This evening, he was just loitering at the intersection as if he were waiting for someone.

Catty-corner from the auto shop, Witness No. 1, still in his roller skates, was hanging around with friends on the Webster Street bridge overlooking the railroad tracks. He once again saw one of the joggers, the pimply one in the blue tracksuit, standing on the corner of Webster behind the local junkyard. He appeared to be waiting for someone, perhaps the other jogger. When Witness No. 1 bent down to adjust his roller skates, he noticed the jogger kept glancing at a silver watch. Witness No. 1 then headed home with his friends, where they watched television.

The popular “Laverne & Shirley” show was airing the penultimate episode of the season, titled “Crime Isn’t Pretty.”

6:45 p.m.

Witness No. 1 and the other kids heard a series of loud pops that weren’t part of the show. They were gunshots.

He ran to the window, only to see the blue jogger one last time, throwing something into a neighbor’s yard before running down Emerson Street in the wake of the gunfire.

Outside his home, the driver of a bullet-ridden vehicle was slumped over the steering wheel as the car careened into a neighbor’s fence.

For clarity, MuckRock has used numerical nicknames to refer to witnesses whose names are redacted within the FBI files. All time stamps are approximate and based on witness statements from 1982.

Header image is a composite image including a suspect sketch via the Somerville Police Department, Orhan Gündüz photo via Anadolu Agency and a photo of the Webster Avenue house by Greer Muldowney.