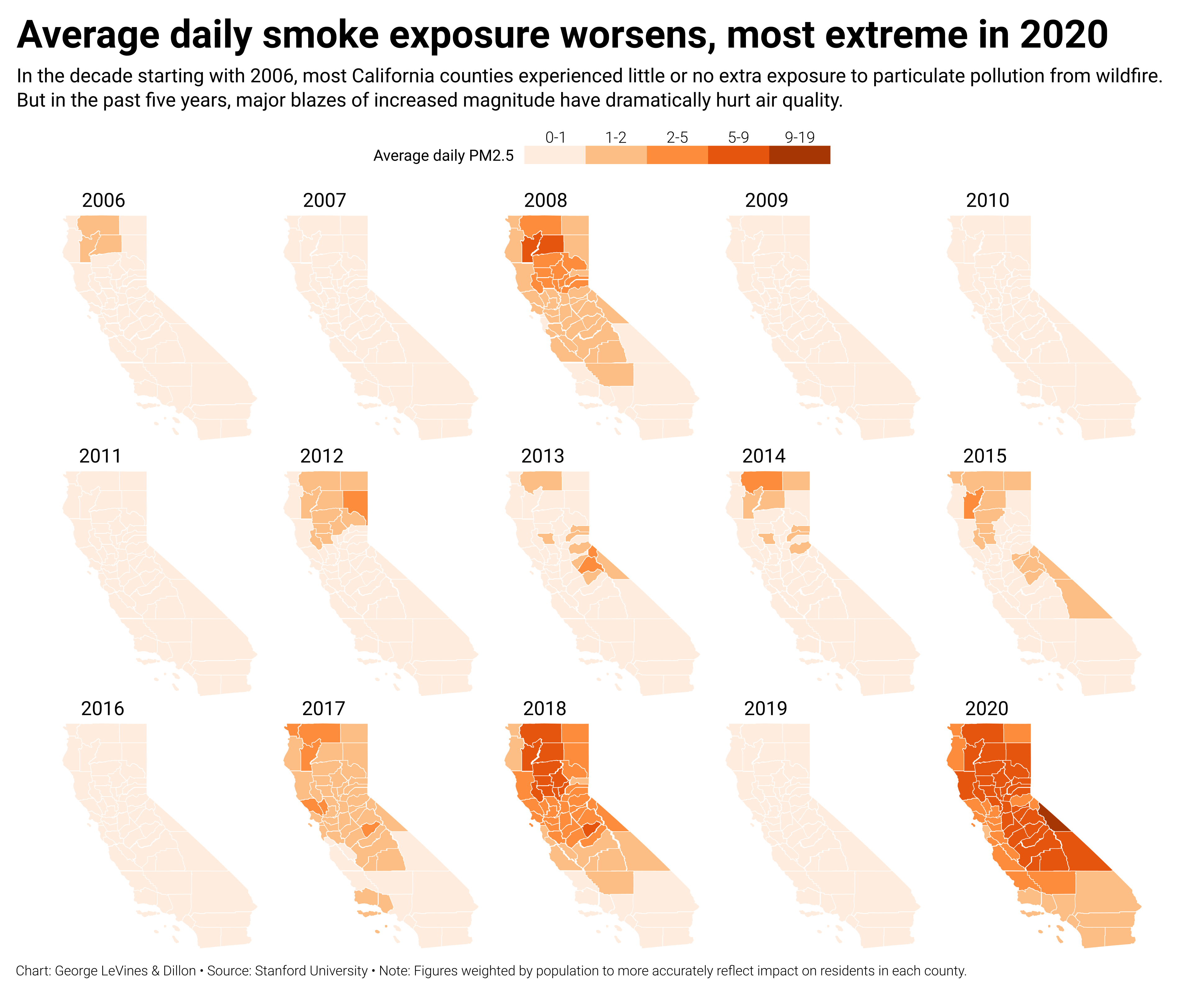

As wildfires have choked skies in the western United States, turning them vivid orange or sickly ochre, millions of people now live where smoke regularly makes breathing unhealthy, according to new estimates from a team based at Stanford University. That includes 21 times more Californians than a decade ago, scattered among vulnerable communities from the Oregon border to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and down through the Central Valley.

“We were shocked by this,” said Marissa Childs, lead author of a paper published this month in Environmental Science and Technology.

Wildland fires spew tiny particles of pollution into the air, one-thirtieth the width of a human hair. Breathed in, they aggravate health problems including asthma, lung and cardiac illnesses. In children, the consequences to their immune systems can be irreversible.

Childs and her colleagues found that in 2020, when five of the largest fires in recorded history burned uncontrolled for many weeks, over 12 million Californians were exposed to at least one day of air so choked with smoke that anyone, including healthy adults, who spent time outside would feel its negative effects. On the federal air quality index, or AQI, these extreme smoke days reach a level of around 175, the middle of the “unhealthy” range.

As a fire year, 2020 is both extreme and part of a broader shift.

During that year, particulate pollution from wildfires was, on average, twice the yearly average of the previous decade, according to an analysis of the paper’s data by The California Newsroom, MuckRock and Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation.

The findings suggest that, for people living around the state, once-rare smoke has become almost routine. A decade earlier, about 200,000 Californians a year lived in areas where they were exposed to extreme smoke days. By 2020, about 4.5 million did.

Childs, who earned her doctorate in environmental studies at Stanford University while working on this research, says it’s far more than she expected when the project began.

“We really underestimated the dramatic increase, especially in extreme days, and the number of people being exposed to even one of these extreme days,” said Childs, now a fellow at the Harvard University Center for the Environment and Harvard School of Public Health.

Measuring how much fires worsen air quality has proven challenging, in part because ground-based federal sensors don’t distinguish soot and ash from particulate matter spewed by other sources, like cars and trucks. To address this, Childs and other scientists used statistical techniques combined with existing meteorological and satellite data to model the intensity of wildfire smoke pollution over time.

Where federal regulation has cleaned up air quality, wildfires may be reversing progress. Patches of Oregon and Washington are especially at risk. Near California’s northern border, in Trinity, Siskiyou, Shasta, Tehama and Glenn counties, pollution from wildfires is 70% higher than the state’s yearly average.

In parts of the state, the risk it compounds is already significant and intractable. The San Joaquin Valley has long exceeded federal limits for particulate pollution, its air fouled by diesel-burning industrial equipment and traffic along the valley’s freeway spines. The valley’s topography worsens the problem: A ring of mountain ranges traps pollution. But wildfire smoke now is making conditions noticeably worse. Based on the reporting team’s analysis, smoke accounts for an estimated one-fourth of the annual federal limit for fine particulate pollution.

“It’s hard to think of another environmental exposure where things have changed so quickly,” said climate economist Marshall Burke, associate professor of Earth system science at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and co-author of the paper.

While that risk has grown, California has deepened its reach into the wildland-urban interface, introducing the twin hazards of more people and more development further into lands that can burn. Along those risky seams, scientists from the U.S. Forest Service and the University of Wisconsin now count more than 5 million homes.

And a changing climate is transforming wildfires themselves, another reason why tracking smoke is difficult. Superheated by tinder-dry vegetation and long, hot summer seasons, wildfires drive smoke higher into the atmosphere, where it can travel far from its source. When that smoke later cools, hundreds or thousands of miles away, descending particulate pollution reacts with sunlight and atmospheric chemicals as it ages.

“It might dissipate, but that doesn’t mean it’s getting safer. A lot of the byproducts get worse over time,” said Dr. Kari Nadeau, who directs the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford Medicine. “Unfortunately, even though it might be less concentrated, it’s more toxic.”

Nadeau, who was not involved in the new research, says those conditions emphasize the importance of the work, which she says “is going to help us understand more about the public health effects,” especially from extreme spikes in smoke pollution.

Katelyn O’Dell, postdoctoral research scientist at George Washington University who has investigated wildfire smoke and health, also called the Stanford team’s work “an exciting advancement.”

“The analysis in the paper highlights the growing threat wildfire smoke poses to public health,” she said.

Knowing with certainty exactly how many people are exposed to fire smoke remains elusive. As a further step toward that goal, Stanford’s Burke says his team hopes to better establish how and when people take shelter from smoky air.

“When things are really bad, they’ll stay inside their home. They don’t go to work, they travel less, like we see all of these changes in behavior,” Burke said. “On days that are less bad, people notice less and they don’t change their behavior.”

Smoke is a democratic hazard, threatening rich and poor Californians. But the ability to take evasive measures from it is uneven. Some people work outside; others live in buildings where air is poorly filtered. That’s why Stanford researchers say their findings point to the growing importance of policies that could minimize smoky threats for large numbers of people at once, even far away.

“We have the tools at our disposal to really change what happens here,” Burke said. By tools, he added, he meant better forest management, including reducing vegetation and using prescribed fires where possible.

“Every year does not have to look like 2020,” he said.

The California Newsroom is a collaboration of California’s public radio stations, NPR and CalMatters. MuckRock collects and shares government documents and works on investigative journalism projects with partner newsrooms.