This post was updated to reflect the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act’s uncertain future after it was removed from the annual Defense spending bill on Dec. 6.

For thousands of families who lived and worked near top-secret nuclear testing sites or uranium processing facilities in the 1940s, 50s and 60s, the road to getting an official apology from the federal government — and financial help for medical bills related to cancers and other diseases — is murky.

On Dec. 6, the expansion of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act was stripped from a congressional defense spending bill, though lawmakers have vowed to continue to champion it. The victims’ fund would have extended health care coverage and compensation to more uranium industry workers and so-called “downwinders” exposed to radiation in several new regions — Colorado, Missouri, New Mexico, Idaho, Montana and Guam — and expanded coverage to remaining parts of Arizona, Nevada and Utah.

It would have also been particularly significant for the Navajo Nation, one of the most affected tribal areas from the world’s first atomic bomb testing in 1945.

The Congressional Budget Office estimated that expanding the compensation program could cost $147.1 billion over 10 years, including $3.9 billion for St. Louis-area victims. After it was pulled from the Senate bill, the amendment’s co-sponsors — Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Missouri; Sen. Ben Ray Luján, D-New Mexico, and Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho — all vowed to fight and keep the compensation fund from expiring next year, and its potential expansion alive.

In late July, the U.S. Senate, with bipartisan support, voted narrowly to expand the program that compensates Americans who become ill because of exposure to radiation from the country’s development and testing of nuclear weapons and the buildup to the Cold War.

President Joe Biden signaled his support for the proposal and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm visited one of the contaminated sites during a visit to St. Louis. Senators attached the legislation to the National Defense Authorization Act, the annual defense bill that still needed approval by the U.S. House of Representatives.

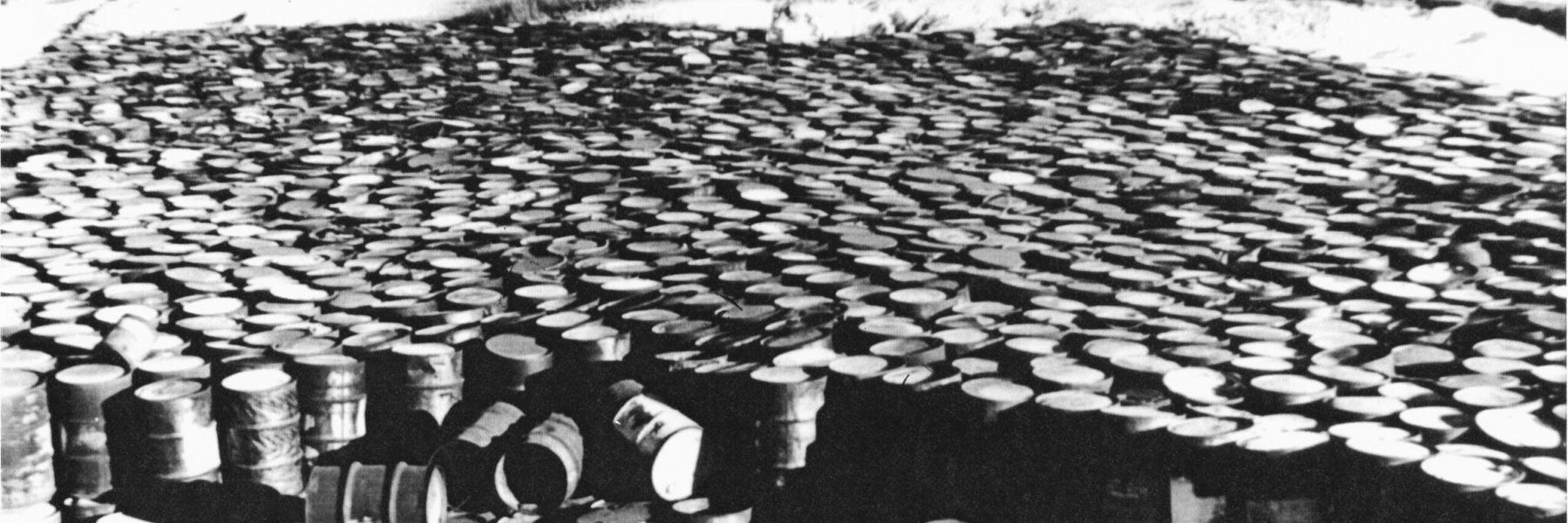

Years of attempts by New Mexico legislators to extend and expand the program, which is set to run out of funding in 2024, had previously failed. But “Oppenheimer,” the new film about the development of the nuclear bomb, brought renewed attention to those impacted. And the latest proposed expansion comes in response to “Atomic Fallout,” an investigation by The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press, which found that, since the late 1940s, private companies and the federal government repeatedly downplayed the potential health risks of contamination in the St. Louis region. In internal memos, they wrote off health risks from exposed nuclear waste leaching into groundwater and neighborhood creeks as “slight,” “minimal” or “low-risk.”

The issue has been covered extensively by journalists over the years but the trove of previously-unreleased documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act laid bare decades of failure that allowed radioactive waste created during the 1940s to linger in the St. Louis region 80 years later. (Read the documents and how journalists used them.)

The reaction from federal and Missouri state lawmakers was swift. Within days, Sen. Hawley, R-Missouri, who introduced the amendment to the Defense bill, and Rep. Cori Bush, D-Missouri, pledged action, calling the investigation “devastating” and decrying the federal government’s “negligence,” and Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey said his office would “do everything in our power to hold the federal government accountable.”

The proposed expansion — adding five additional states and the territory of Guam and significantly expanding regions of three other states — would have resulted in at least tens of thousands of additional claimants.

Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act Program began more than 20 years ago, in April 1992, more than 54,000 claims have been filed. Of those more than 40,000 claims, or about 75%, have been approved and roughly $2.6 billion has been paid out, as of the end of 2022. Claims for “downwinders” and uranium workers typically range from $50,000 to $100,000. The Department of Justice’s civil division, which oversees the program, says that, of the denials, just 16 claimants have appealed their determinations in federal district court.

Definitively proving that exposure to nuclear waste and radiation caused cancers and other diseases is difficult. But the federal program doesn’t require claimants prove causation. They only have to show that they or a relative had a qualifying disease after working or living in certain locations during specific time frames. In Missouri, for example, the affected areas in the proposed amendment include 20 ZIP codes and residents have to show they lived there for at least two years, from 1949 onward.

A federal study released in 2019 of one of the most heavily impacted sites, Coldwater Creek in North St. Louis County, found elevated rates of breast, colon, prostate, kidney and bladder cancers as well as leukemia in the area. Childhood brain and nervous system cancer rates are also higher.

We want to hear from those who were impacted by fallout from nuclear development and testing, and who could be impacted by RECA expansion. Fill out the form below and a journalist may reach out to you to get more information.

Photo Credit: State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection, 1943-2006.