Legislation that would have compensated St. Louis-area residents exposed to decades-old radioactive waste was stripped from a federal defense bill, leaving individuals who have suffered rare diseases without government assistance.

This summer, the Senate amended the National Defense Authorization Act to expand the existing Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to include parts of the St. Louis region where individuals were exposed to leftover radioactive material from the development of the first atomic bomb. It would have also included parts of the Southwest where residents were exposed to bomb testing.

But the provision was removed Wednesday by a conference committee of senators and members of the U.S. House of Representatives working out differences between the two chambers’ versions of the bill.

Even before the text of the amended bill became available Wednesday night, U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri was decrying the removal of the radiation compensation policy.

“This is a major betrayal of thousands and thousands of Missourians who have been lied to and ignored for years,” Hawley, a Republican running for reelection next year, said in a post on social media.

Dawn Chapman, a co-founder of Just Moms STL, fought back tears Wednesday night as she described hearing the “gut-wrenching” news from Hawley’s staff. Chapman and fellow moms have been advocating for families exposed to or near radioactive waste for year.

“I actually thought we had a chance,” Chapman said. But she said the group hopes to get the expansion passed another way.

“Nobody has given up on it,” Chapman said.

The St. Louis region has suffered from a radioactive waste problem for decades. The area was instrumental in the Manhattan Project, the name given to the effort to build an atomic bomb during World War II. Almost 80 years later, residents of St. Louis and St. Charles counties are still dealing with the fallout.

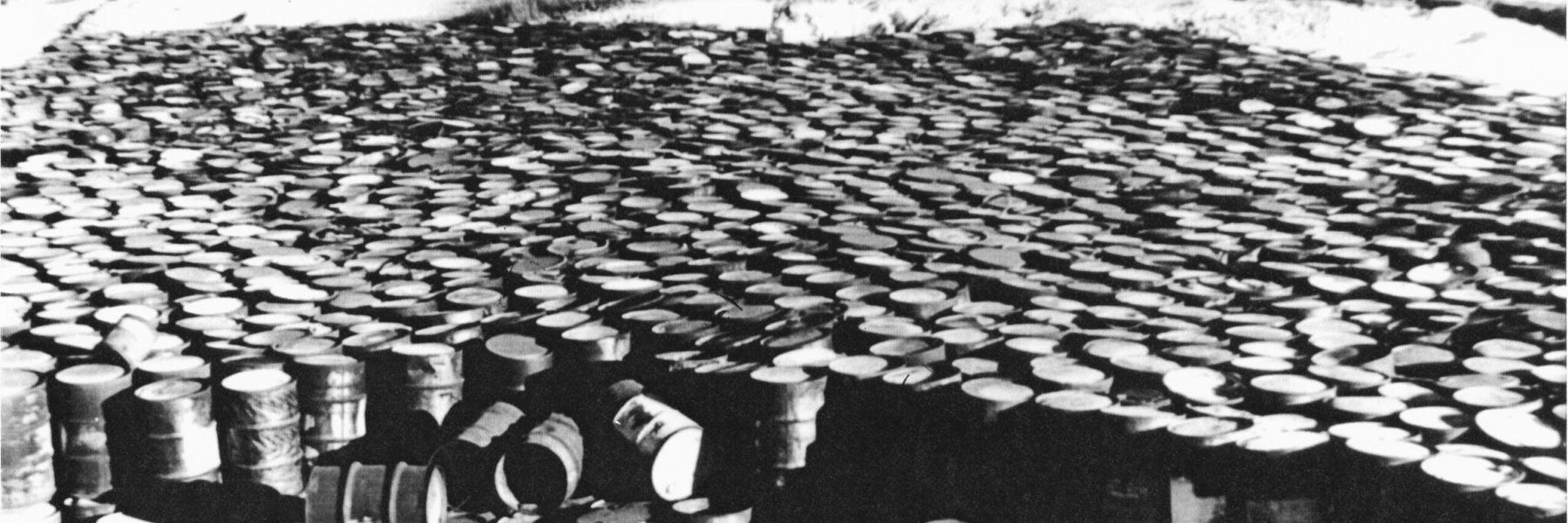

After the war, radioactive waste produced from refining uranium was trucked from downtown St. Louis to several sites in St. Louis County where it contaminated property at the airport and seeped into Coldwater Creek. In the 1970s, remaining nuclear waste that couldn’t be processed to extract valuable metals was trucked to the West Lake Landfill and illegally dumped. It remains there today.

During the Cold War, uranium was processed in St. Charles County. A chemical plant and open ponds of radioactive waste remained at the site in Weldon Spring for years. The site was remediated in the early 2000s, but groundwater contamination at the site is not improving fast enough, according to the Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

For years, St. Louis-area residents have pointed to the radioactive waste to explain rare cancers, autoimmune diseases and young deaths. A study by the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry found people who lived along Coldwater Creek or played in its waters faced an increased risk of cancer.

Chapman said she knew two individuals who made calls to members of Congress while receiving chemotherapy. It’s hard to ask people to keep fighting for the legislation, she said.

“They’re not going to see another Christmas, and they’re not going to see the compensation from this,” Chapman said. “This won’t help them.”

An investigation by The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press this summer found that the private companies and federal agencies handling and overseeing the waste repeatedly downplayed the danger despite knowledge that it posed a risk to human health.

After the report was published, Hawley decried the federal government’s failures and vowed to introduce legislation to help.

So did U.S. Rep. Cori Bush, D-St. Louis. In a statement Wednesday night, she said the federal government’s failure to compensate those who have been harmed by radioactive waste is “straight up negligence.”

“The people of St. Louis deserve better, and they deserve to be able to live without worry of radioactive contamination,” Bush said.

Missouri’s junior senator, Republican Eric Schmitt, grew up near the West Lake Landfill. He said in a statement that the “fight is far from over” and that he will look into other legislation to get victims compensation.

“The careless dumping of this waste happened across Missouri, including in my own backyard of St. Louis, and has negatively impacted Missouri communities for decades,” Schmitt said. “I will not stop fighting until it is addressed.”

Already, two state lawmakers have pre-filed legislation related to radioactive waste in advance of the Missouri General Assembly reconvening in January. One doubles the budget of a state radioactive waste investigation fund. The other requires further disclosure of radioactive contamination when one sells or rents a house.

In July, the U.S. Senate voted narrowly to adopt Hawley’s amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act expanding the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to include the St. Louis area. It would have also expanded the coverage area to compensate victims exposed to testing of the atomic bomb in New Mexico. The amendment included residents of New Mexico, Colorado, Idaho, Montana and Guam and expanded the coverage area in Nevada, Utah and Arizona, which are already partially covered.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that expanding the program could cost $147.1 billion over 10 years with St. Louis’ portion taking up $3.7 billion of that.

The amendment would have also renewed the program for existing coverage areas. Without renewal, it will expire in the coming months.

Hawley said, however, the “fight is not over.”

“I will come to this floor as long as it takes. I will introduce this bill as long as it takes,” he said. “I will force amendment votes as long as it takes until we compensate the people of this nation who have sacrificed for this nation.”

This story will be updated.

Illustration by Tyler Gross (Riverfront Times).