The Missouri Independent and MuckRock spent months scouring thousands of pages of government records about St. Louis’ involvement in the race to build an atomic bomb during World War II and decades of environmental contamination that followed.

Journalists sought to lay bare the degree to which government officials knew of the spreading contamination and the danger it posed to St. Louis County residents.

While the contamination at the West Lake Landfill and in Coldwater Creek has been covered extensively for decades, documents obtained by the newsrooms revealed the way federal officials failed to take stronger measures to protect the health of St. Louis-area residents.

You can read the full investigation here.

Here are five key takeaways:

A company that refined uranium for the Manhattan Project knew as early as 1949 that radioactive residue could pollute Coldwater Creek

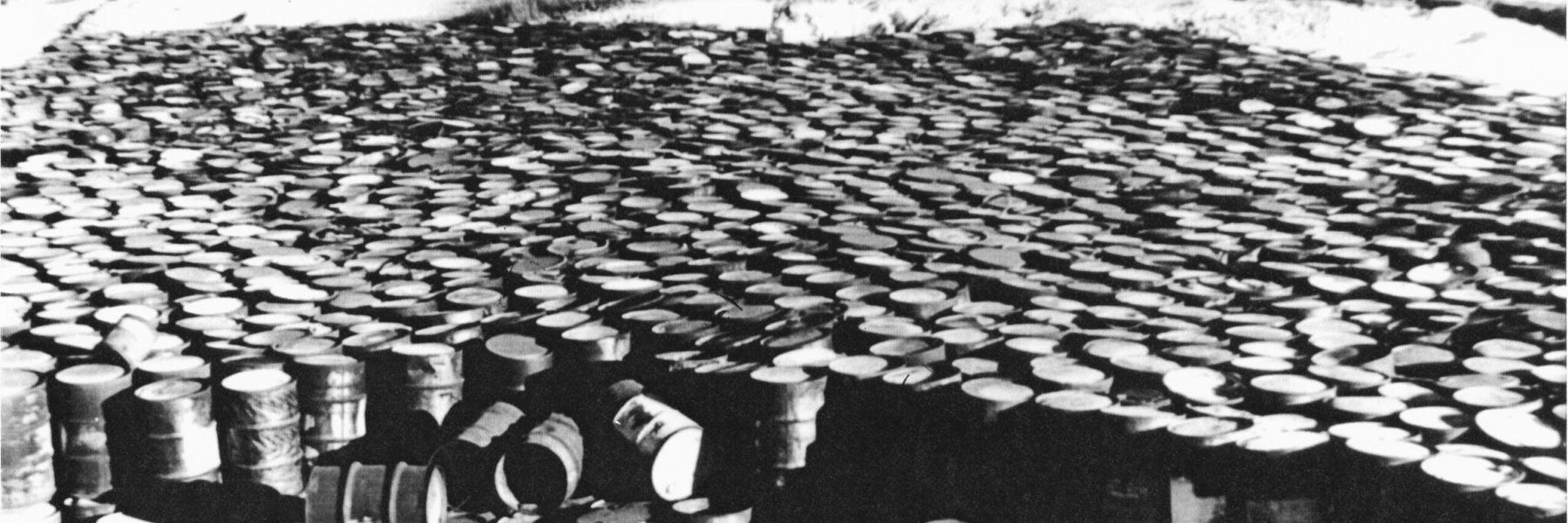

Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, which refined uranium in downtown St. Louis, stored barrels of K-65, a radioactive residue, at the St. Louis airport in deteriorating steel drums. In 1949, a Mallinckrodt memo shows, the company was aware the broken drums could result in runoff pollution to Coldwater Creek. But it determined the threat to workers from attempting to move the drums would be worse.

A draft survey commissioned by federal government in 1976 showed dangerous levels of contamination running off into Coldwater Creek

A report from a 1976 site visit and survey found rainwater run-off had eroded the soil and formed a large ditch at the edge of the St. Louis airport storage site, carrying contamination into Coldwater Creek. Tests showed elevated concentrations of radionuclides in the creek sediment, though the creek water was within permissible levels.

An expert who reviewed the document for The Missouri Independent and MuckRock said the 1976 dose readings at the site were “far higher than what is allowed.”

The Cotter Corp. pushed the Atomic Energy Commission to let it dump radioactive waste at a quarry in Weldon Spring before illegally dumping it in the West Lake Landfill

After World War II, the Atomic Energy Commission sought a buyer for radioactive waste. It planned to let a company extract valuable metals from the residue and dump the rest in a quarry in Weldon Spring just outside the banks of the Missouri River.

The U.S. Geological Survey discouraged the dumping plan because it would likely contaminate the river just upstream from where residents’ drinking water was drawn. When the AEC backtracked on the plan, the Cotter Corp., which had dried and shipped valuable materials to its uranium mill in Colorado, was left struggling with how to dispose of the leftover residue and asked to dump it in the quarry or bury it at a site in Hazelwood. The company ended up taking it to the free West Lake Landfill and illegally dumping it there in 1973.

Despite warnings that further testing was needed, federal officials believed the contamination at the West Lake Landfill was confined to two areas because of a 1977 flyover test

In the late 1970s, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which replaced the AEC, flew a helicopter over the West Lake Landfill. It used gamma readings in an attempt to determine what parts of the landfill were contaminated with the radioactive waste the Cotter Corp. dumped there.

The test correctly identified two contaminated areas but missed huge areas of the landfill.

Despite warnings from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and activists that the contamination was likely more widespread, the NRC’s conclusion stood for more than 40 years.

This spring, the Environmental Protection Agency announced the contamination at the site was more widespread than previously thought.

Radium activity at the West Lake Landfill is expected to increase in the coming years

Testing performed in the 1980s and a more recent analysis by a former Washington University researcher concluded that radium activity is expected to worsen over time because the radionuclide is out of balance with thorium and uranium at the site.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission wrote that this means the health and environmental hazards from radium at the site will get exponentially worse over the ensuing 200 years.