This story has been updated to include a response from the Department of Energy and details about U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley’s campaign committee being refunded most of the donation it received from Mallinckrodt in 2019.

Weldon Spring — U.S. Sen. Josh Hawley on Thursday decried the federal government’s “negligence” that allowed radioactive waste to sicken St. Louis-area residents for decades and invited Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm to visit the community still suffering from the legacy of the atomic bomb.

“You all have had enough of it,” Hawley said. “I’ve had enough of it. It’s time to put a stop to this.”

But even as he joined activists and a bipartisan coalition of state officials calling for federal action, Hawley faced questions about his own environmental track record during his two years as Missouri’s attorney general.

And activists said they have had no luck getting a meeting to discuss the issue with the current attorney general, Andrew Bailey. Bailey’s office said earlier in the day that it will work to hold the federal government accountable.

Speaking at a news conference in Weldon Spring attended by Republican and Democratic elected officials, Hawley addressed the findings of a six-month joint investigation by The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press that revealed that for decades government agencies and private companies downplayed or failed to fully investigate radioactive contamination stemming from the effort to build the first atomic bomb during World War II.

“We’re here because for 75 years…the federal government has poisoned the water, the soil and the air of this community and has lied about it,” Hawley said.

The issue has been covered extensively by journalists over the years, but a trove of previously-unreleased documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act and reviewed by the three newsrooms laid bare decades of failure that allowed radioactive waste created during the 1940s to linger in the St. Louis region 80 years later.

U.S. Rep. Cori Bush was in Washington for votes, but her aide read a statement saying the new findings confirm what the community already knew — that the “federal government actively and knowingly treated St. Louis as a dumping ground for harmful and toxic radioactive waste.”

“The federal government must not continue to allow our communities to be further collateral damage,” Bush said in her statement.

State Rep. Tricia Byrnes, R-Wentzville, said the region has become “desensitized to the insanity.”

Hawley, a Republican and Missouri’s senior U.S. senator, joined activists from Just Moms STL in calling on the Department of Energy to finance cleanups of nuclear sites across St. Louis and St. Charles counties and reiterated his pledge to introduce legislation to compensate individuals who have contracted rare cancers or autoimmune disorders because of radioactive exposure.

In an email Thursday evening, the Department of Energy said it does “not underestimate the impact that nuclear research and the production of nuclear weapons had on communities.

“The department proudly works alongside partners at the federal, state and local levels, including in Missouri, to protect the health and safety of community residents, and protection of the environment,” the statement said.

But Hawley faced questions about his decision to eliminate the environmental division of the Missouri attorney general’s office shortly after he took it over in 2017, as well as his campaign’s acceptance of contributions from companies that created or handled the nuclear waste.

Hawley’s decision to eliminate the environmental division raised concerns at the time that the attorney general wouldn’t prioritize defending Missouri’s natural resources.

It was among his first decisions in office, one former staffer told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch at the time, and sent a “chilling message” that the environment “was no longer what he considered to be an important part of the mission.”

At Thursday’s news conference, Hawley denied that the division was dissolved. Rather, he said, the entire attorney general’s office was restructured, though he couldn’t recall what division included environmental enforcement.

But he said “we held those guys accountable,” referring to a settlement Hawley’s office reached in a lawsuit filed by his predecessor, Democratic Attorney General Chris Koster, against Republic Services, which owns the West Lake Landfill in Bridgeton.

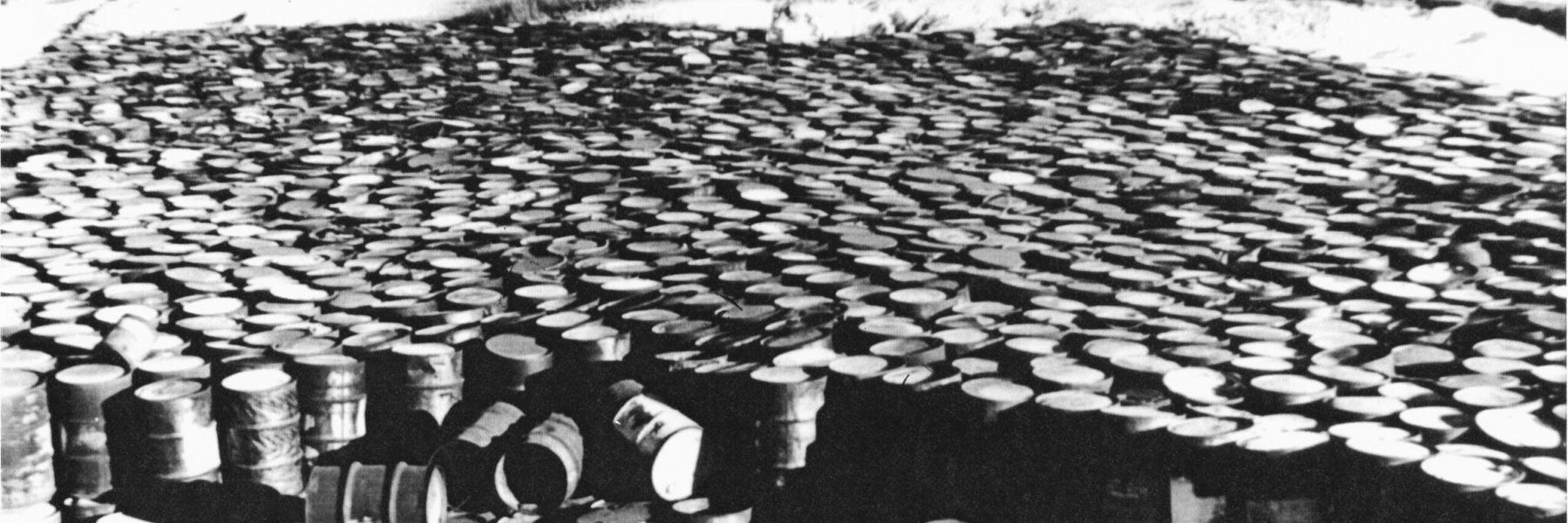

The landfill has held thousands of tons of radioactive waste and contaminated soil since 1973 when it was dumped there against the regulations of the Atomic Energy Commission by a contractor for the Cotter Corporation.

Dawn Chapman, co-founder of Just Moms STL, said that settlement provided a free clinic for the community.

Hawley was also asked whether he would return the combined $5,000 his state campaign committee and federal leadership political action committee received from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, which refined uranium for the federal government in the 1940s as Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, and Republic Services. Of the $2,500 Hawley received from Mallinckrodt during his campaign for attorney general in 2016, $2,254 was refunded when the committee was terminated following Hawley’s 2018 election to the U.S. Senate. Senate leadership political action committees in 2018 also received $250,000 from General Atomics and employees, the parent company of Cotter.

He said he would look into it.

Elad Gross, who served in the attorney general’s office under Koster and is making his second run for the Democratic nomination for attorney general next year, attended the news conference and said the state desperately needs an environmental division.

“Look at where we are right now,” Gross said. “We’ve got folks in the press who are doing great work and getting this information out to the public faster than the attorney general is investigating it…so we’re obviously seeing what happens when you don’t have a dedicated conservation division in that office.”

But Chapman said when Hawley replaced Koster, he reached out to her and other activists and pledged support for them. The attorneys working on the case against Republic, she said, never changed.

“I can only speak to how hard his office worked,” Chapman said, adding she had the same access to Hawley that she did Koster.

But Chapman said she and fellow Just Moms STL co-founder Karen Nickel haven’t heard from Bailey despite the fact that they provided his office in May thousands of pages of documents reviewed by The Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press.

Bailey faced criticism Wednesday and calls to sue the federal government over the findings of the investigation.

On Thursday, Bailey broke his silence, issuing a statement saying he assigned an attorney to investigate the issue when his office received the documents from Chapman and Nickel.

“We will convey our findings to the appropriate parties,” Bailey said, “and we will do everything in our power to hold the federal government accountable.”

Chapman and Nickel said they still hope to hear from Bailey or someone in his office.

“You’ve really got to come here and meet us and let us show you what you’re seeing in these documents,” Chapman said. “That’s all I’m asking.”

A sick community

The renewed attention brought to St. Louis’ legacy of radioactive contamination was cathartic for a community that, for years, has watched as friends and family members were lost to mysterious cancers or suffered with chronic illnesses.

Byrnes said she first found out about the radioactive contamination when her son developed cancer. Growing up, she swam in a quarry in Weldon Spring just outside the banks of the Missouri River, never knowing it was contaminated with nuclear waste.

![An undated photo from the 1980s, of a child swinging from a rope into Coldwater Creek. The photo is from a scrapbook kept by Sandy Delcoure, who lived on Willow Creek in Florissant and donated the scrapbook to the Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection. Only one of the photographs from the scrapbook includes any information, which read: “Willow Creek children on Cold Water [sic] Creek. We can’t keep the children away from the creek. The only alternative is to get it cleaned up.” (State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection, 1943-2006.)](https://cdn.muckrock.com/news_photos/2023/07/11/Archive-01.jpg)

For a long time, when she talked about the issue, Byrnes said she would preface her speech: “I’m going to sound crazy.”

“For the first time ever,” Byrnes said, “I woke up this morning not feeling crazy.”

Byrnes attended Francis Howell High School in Weldon Spring. Driving southwest on Missouri Highway 94, just after the school baseball fields, the road bends and a mound of rock becomes visible on the right.

It’s the highest point in St. Charles County, and underneath lies rubble and nuclear waste from Cold War-era uranium processing. Residents can walk to the top of the pile, which contains the rubble from the Mallinckrodt plant that stood there and pits where nuclear waste was stored.

Children continued to attend the high school during the cleanup in the 1990s.

When Christen Commuso, a spokesperson for the nonprofit organization the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, was growing up in north St. Louis County, she didn’t know about contamination at several sites nearby.

Commuso said within a year in 2012, she had a total hysterectomy and an adrenal gland gland and her gallbladder removed. She developed a tumor on her other adrenal gland and suffered from thyroid cancer.

“I’m still living with the consequences,” she said.

State Rep. Doug Clemens, D-Place, found out at age 13 that he shouldn’t be playing in Coldwater Creek, which was contaminated by runoff from nuclear waste storage sites, from Kay Drey, an activist who spearheaded grassroots efforts to advocate for the cleanup of St. Louis County sites starting in the 1970s.

“Our whole region is injured by this — psychologically, emotionally, physically,” Clemens said.

Nickel said Coldwater Creek was a part of her neighborhood growing up. She played in St. Cin Park, right next to the creek. The park had to be remediated because of radioactive contamination.

Now Nickel lives with several autoimmune disorders. Her five-year-old granddaughter was born with cysts on her ovaries. Nickel’s sister, too, suffered from ovarian cysts as a child.

Getting compensation

Just getting the sites cleaned up isn’t enough for Hawley, who pledged on Wednesday to introduce legislation requiring the federal government to pay medical bills for St. Louis area residents sickened as a result of radioactive waste.

He said it would be similar to legislation that offered the same to “Downwinders,” residents who became sick after being exposed to radiation from testing of nuclear weapons in western states during World War II.

Hawley said it shouldn’t be on sick residents to prove their illness was caused by radiation. If they have a disease linked to radiation exposure and lived in the area during the period, he said, they should receive compensation.

“Victims shouldn’t be on trial,” Hawley said.

Asked if the private companies — Mallinckrodt, Cotter and Republic — that have handled the waste or overseen the West Lake Landfill should bear some of the financial burden, Hawley said he hopes there will be “some legal recourse.” He said he hoped those who could bring a legal case against the companies would “bring the heat.”

“I’ll do everything I can legislatively,” he said.

Hawley pledged to ask U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin, D-West Virginia, who chairs the Senate Energy Committee, to hold hearings about the St. Louis-area nuclear waste.

“In one sense, I say the federal government should make people whole,” Hawley said, “but we all know that the time to make people truly whole has passed because of the government’s negligence.”