This post has been updated to include a DocumentCloud link to all of the keyword-searchable “Atomic Fallout” documents and additional details about how they were used by journalists.

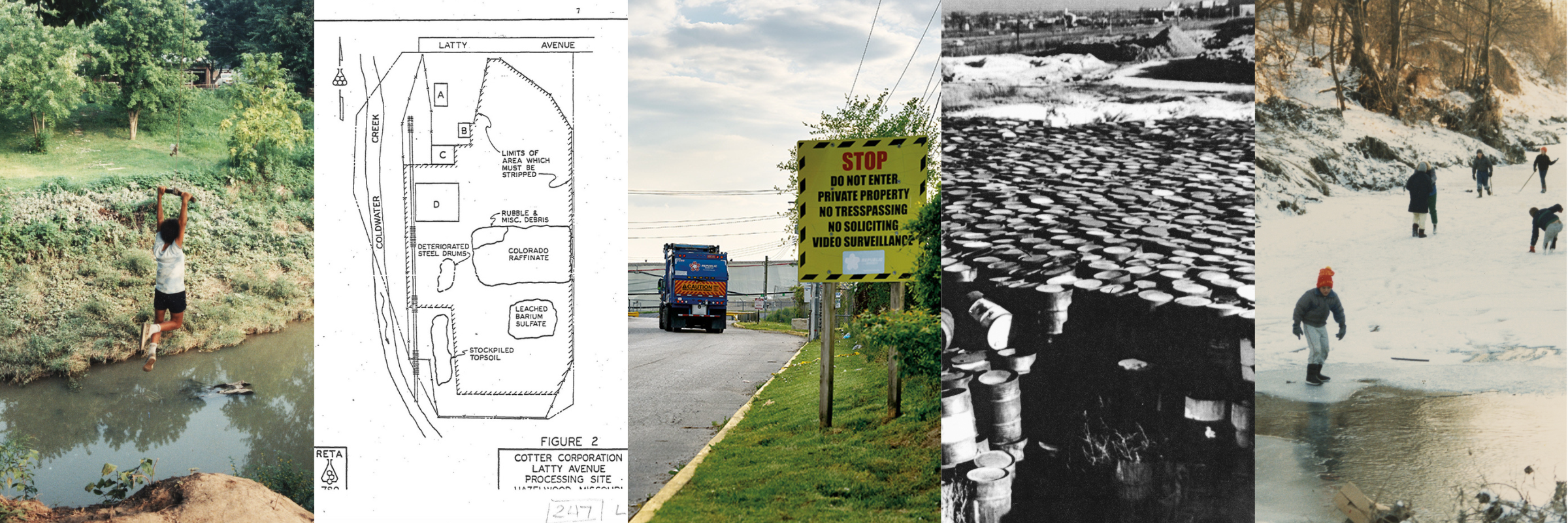

“Atomic Fallout” is a historical re-investigation of the St. Louis region’s 75-year history with nuclear waste, conducted by a consortium of newsrooms, including The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press. It relies on thousands of pages of federal government documents, most of which were obtained through the Freedom of Information Act.

Many of the documents have either been newly-declassified or never before reviewed.

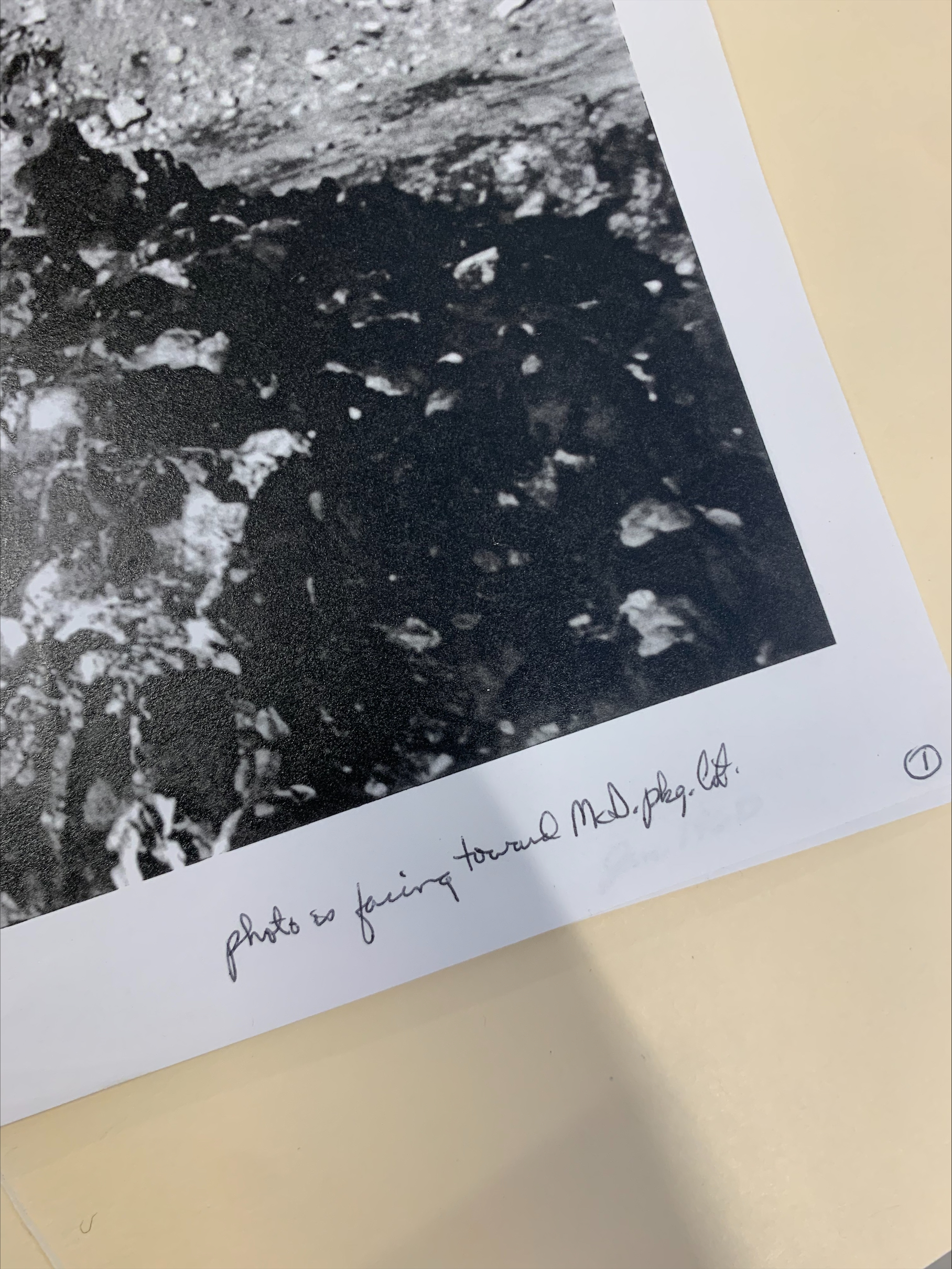

To better understand the records, journalists from different organizations spent the past six months researching and annotating them. We consulted experts to analyze the government memos and testing results anew, to see if the environmental and radioactivity testing done decades ago could be seen and understood in a different, modern light. We also tried to answer a question that Missouri state agencies, elected officials and local residents repeatedly asked government agencies and private companies, with little success:

What did the federal government and private companies know about the potential risks to public health posed by the nuclear waste and when?

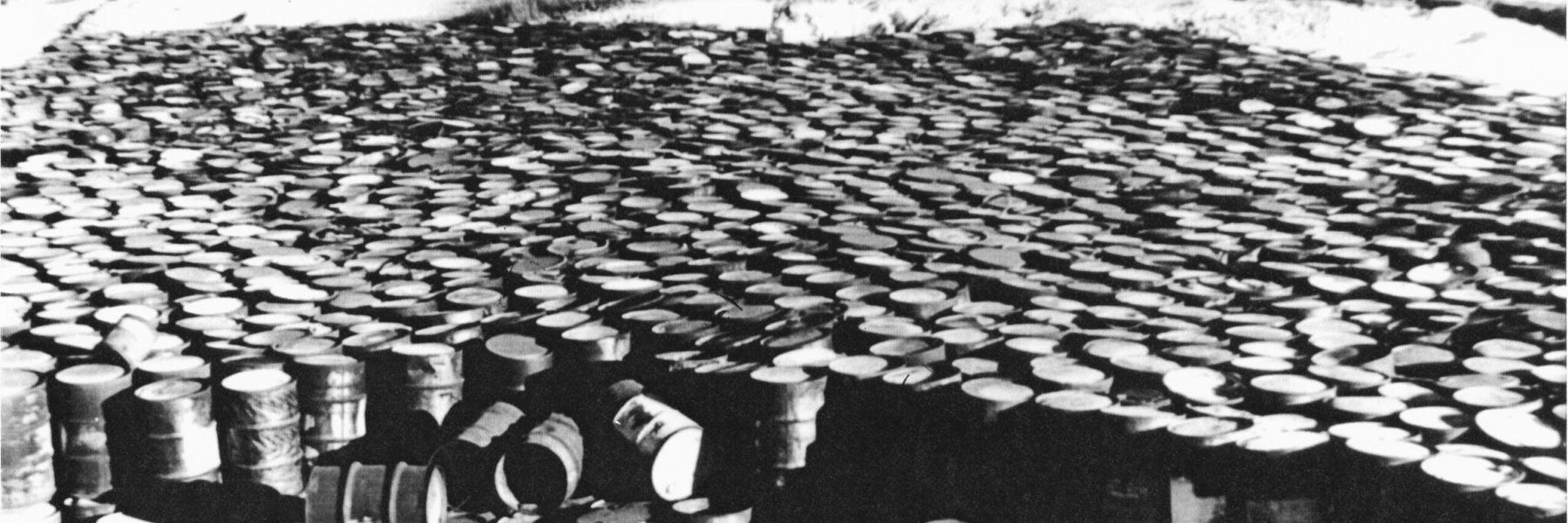

What we found shows, for the first time, that Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, which processed uranium in the St. Louis area for the Manhattan Project, and government agencies it contracted with, including the Atomic Energy Commission, the precursor to the Department of Energy, knew as far back as 1949 that Coldwater Creek could be contaminated by radioactive waste flowing from deteriorating steel drums.

We found multiple points in time — in the 1960s, 70s and 80s — where federal agencies knew about spreading contamination into soil, groundwater and a creek neighborhood children played in and wrote it off as “slight,” “minimal” or “low-level.”

And, with the passage of time and the improved knowledge about the effects of thorium, radium and other nuclear residues on human health, experts helped us piece together how bad the ionizing radiation was for the environment and the people who lived near it, and how it could have played a role in the documented increase in cancers in the surrounding areas.

We found similar downplaying of human health and environmental risk at nearby nuclear waste sites, including the West Lake Landfill and Weldon Spring.

Where the documents came from and how we used them

Many of the government documents we obtained were not declassified until the 2000s and, in the absence of draft and final reports from the Atomic Energy Commission, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the Department of Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency, many of the details were left out of the public record.

That void has, at times, fed outsized public concern. Definitively linking cancer to radiation exposure, known as proving a “cancer cluster,” is notoriously difficult, experts told us, and the data from both the West Lake Landfill and the runoff from Coldwater Creek doesn’t suggest a current public health threat. Still, a 2019 federal study by the CDC’s Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry found elevated rates of breast, colon, prostate, kidney and bladder cancers as well as leukemia in the area in recent decades. Childhood brain and nervous system cancer rates are also higher.

The Freedom of Information Act requests were filed by Lucas Hixson, a nuclear researcher who has written extensively on the Chernobyl disaster and co-founded the Clean Futures Fund, a nonprofit that raises awareness and provides support for communities affected by industrial accidents and long-term remedial activities. In 2015 and 2016, with the help of a law firm, Hixson requested documents related to the West Lake Landfill and Coldwater Creek from a host of government agencies.

The documents produced through Hixson’s requests totaled more than 29,000 pages, released in batches between 2017 and 2020. Some were duplicative and others were fairly mundane so Hixson flagged hundreds of documents that, in his opinion, were notable and shared them with a number of advocacy groups, including Just Moms STL. But we wanted to go a step further, and see what the government had produced in total. So we re-requested the FOIAs from the agencies and downloaded the full document sets.

Many carried “Classified” markings and, in turn, declassification stamps, including dates they were declassified and the reason they were kept from public view in the first place, such as the Atomic Energy Act of 1954.

A group of journalists spent weeks carefully reading through the documents while using DocumentCloud to categorize different types of documents, record the date of the document and flag the types of information the document contained. The goal of this massive undertaking of reading and annotating was to help reporters connect the dots between documents across decades of history. Attaching more information onto each document in DocumentCloud then allowed reporters to sort and filter documents quickly.

This system also enabled reporters to take that information out of DocumentCloud using an Add-On on for scraping metadata on DocumentCloud and organize the documents into a timeline.

Reporters did not use any type of AI or machine learning assistance given the deeply technical and nuanced nature of many of the records. They added relevant tags to each record along with notes and questions to pose to experts.

Asking experts, the public and fellow journalists for help

MuckRock and The Missouri Independent then sent some of the more notable documents, including those that included air, soil and water readings, to a group of experts, some with deep connections to the St. Louis nuclear waste story and others who had only read about it in passing.

Robert Criss and Lee Sobotka are longtime professors from Washington University in St. Louis; Criss is a geologist and Sobotka is a physicist and both are well versed in the minutiae of the West Lake Landfill and the nuclear waste left there. Criss has oftentimes been fiercely critical of the federal government while Sobotka has cautioned that federal agencies weren’t necessarily acting with intentional malice and the current health risks were low.

Still, after reviewing the documents for our project, they largely came to the conclusion: The West Lake Landfill and the radioactive waste running off into Coldwater Creek is an environmental and public health flashpoint that will require close attention for generations to come. And the government made repeated mistakes in how they handled that waste and what they told the public.

We launched a public callout to collect stories from those who lived near Coldwater Creek and the West Lake Landfill. We heard from dozens of current and former residents of Florissant and Hazelwood, many of whom said they never knew about radioactive waste that had been dumped nearby.

We also attended an important community meeting held in May between residents and the Environmental Protection Agency, which, since 1995, has overseen the West Lake Landfill as a federally-designated Superfund site. Handouts included and a way for residents to fill out a form about their experiences.

From those submissions, we set out to interview each one who was willing to talk to us, along with another set of residents who had testified in Jefferson City. A group of University of Missouri students, led by Virginia Young, a former Post-Dispatch reporter and bureau chief, and Mark Horvit, a former president of Investigative Reporters and Editors who now runs the school’s Jefferson City Capitol reporting program, conducted those interviews and they provided the narrative backbone for “Atomic Fallout.”

We also shared some of our lead findings with those who have covered the St. Louis nuclear story, including Carolyn Bower and Gerry Everding, who were part of the original St. Louis Post-Dispatch team that published “Legacy of the Bomb” in 1989. Their expertise proved invaluable. And we compared the findings with the public record — government reports like the 2019 federal CDC study; community-led working groups, like one convened about the St. Louis airport in 1994; and media accounts.

Our top five takeaways from our work can be found here.

If you have questions for us about this project or our work, feel free to email us at fallout@muckrock.com.