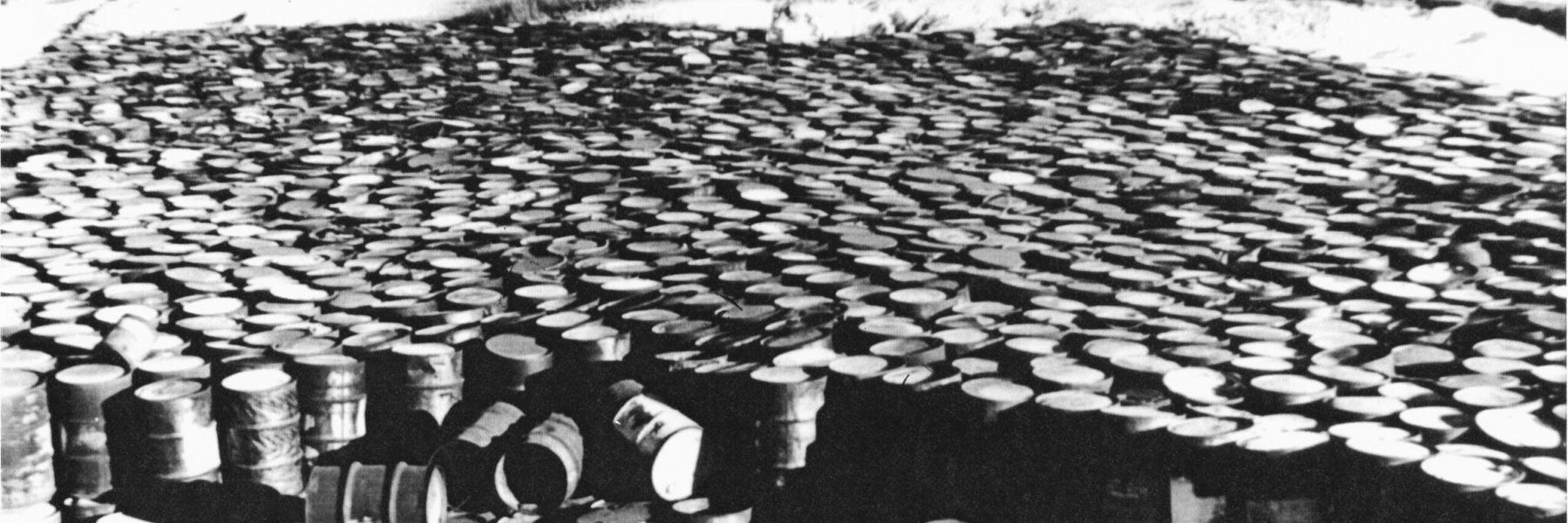

BRIDGETON, Mo. — Radioactive waste in the West Lake Landfill is more widespread than previously thought, officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said Tuesday.

The finding is based on two years of testing at the St. Louis County site, which has held thousands of tons of radioactive waste for decades. An underground “fire” in another area of the landfill threatens to exacerbate the issue, which residents believe is responsible for a host of mysterious illnesses.

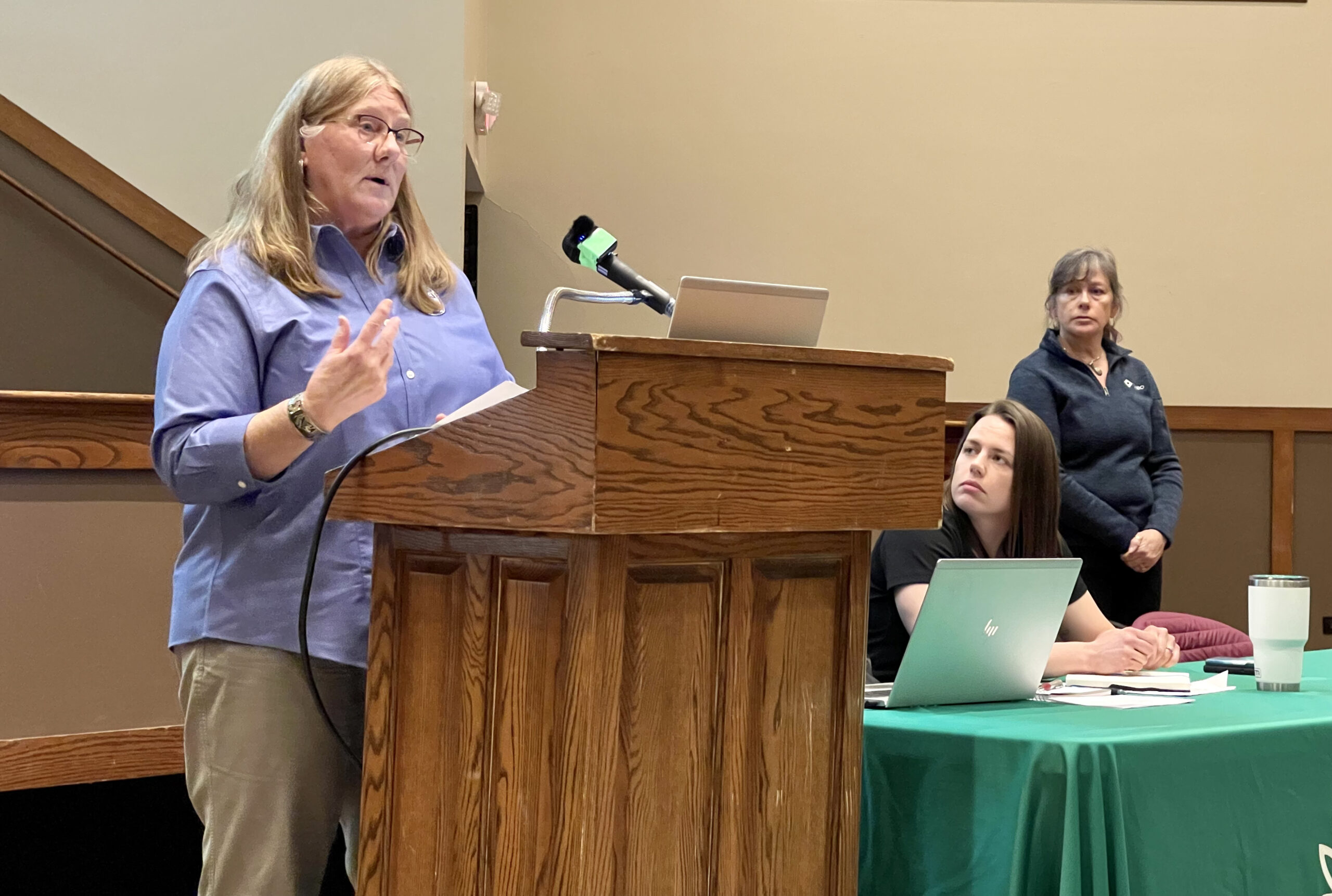

Chris Jump, the EPA’s remedial project manager for the site, said the findings don’t change the agency’s planned cleanup strategy or the level of risk the site poses to the surrounding residents. The radioactive waste is still within the footprint of the landfill, she said.

“The site boundaries themselves aren’t expanding, but the area that will need the radioactive protective cover is larger than previously known,” Jump said to a crowd of about 50 Tuesday night at the District 9 Machinists hall in Bridgeton.

The Missouri Independent and MuckRock are partnering to investigate the history of dumping and cleanup efforts of radioactive waste in the St. Louis area.

St. Louis was pivotal to the development of the atomic bomb during World War II, and community members say they’re still suffering. Waste from uranium processing in downtown St. Louis — part of the Manhattan Project — contaminated Coldwater Creek, exposing generations of children who played in the creek and most recently forcing the shutdown of an area elementary school.

And though the site was placed on the National Priorities List more than 30 years ago, meaning it is among the most contaminated hazardous waste sites in the country, the EPA wouldn’t commit to a timeline for the cleanup during Tuesday’s meeting.

“I know this is not what people want to hear,” Jump said, adding that federal law requires certain steps for Superfund sites. “I’m sorry. I can’t give you a specific timeframe.”

Jump’s comments came at a meeting held by the EPA to present the results of interviews with area leaders and activists and propose a plan for better communicating with the community around the site. She said the agency is still reviewing the full report about the additional radioactive areas and will return to present that information on May 9.

The findings, Jump said, show that there is radioactive contamination in parts of the landfill that the EPA didn’t think were impacted. Jump said radioactive material was found at the surface of the landfill in a restricted area. It was quickly covered with rock, she said. And a drainage ditch between the West Lake site and the road had contamination between two and 10 feet below the surface.

Karmen King, who provides technical assistance to community members as a contractor for the EPA, and Jessica Evans, the EPA’s community involvement coordinator at the site, committed to listening to the community.

King, who recently replaced a contractor who retired, presented the results of her interviews and research on the community’s needs.

“Some of the top concerns that the interviewees vocalized was starting with rebuilding trust,” she said. “The historic meetings and communication — folks felt like the information wasn’t transparent.”

Jump said she wasn’t surprised by the finding that people didn’t trust the agency.

“We’re glad to know that and we would like to do better,” Jump said.

To activists and community members who have been pushing the EPA to take steps to provide greater protection for residents and listen to their concerns for a decade, the federal agency’s new plan seemed too little too late. Several in the crowd said they had been to meeting after meeting and nothing had changed at the site.

Jim Usry, chief of the Pattonville Fire District, pressed Jump for a timeframe for the cleanup.

“Is it in the next five years? Is it in the next 10 years?” Usry said.

Usry noted that many in the audience had been to numerous meetings about the EPA’s progress at the site.

“This is probably the fourth team that I’ve seen in front of me telling me the same thing I heard back 10 years ago,” Usry said. He asked Jump to tell him a decade when the site would be cleaned up.

From the back of the room, someone shouted: “A decade would be nice before I hit 92.”

Jump said the amount of time the EPA needs to review plans and documents can vary widely as can back-and-forth questions and comments with parties involved in the cleanup.

“Within a decade, yes, I hope we have a design by then,” Jump said. “I assume we will, but I cannot provide a specific timeframe.”

Jump said part of the reason she couldn’t provide a specific time frame was that the EPA had done so in the past and missed its targets.

One resident of Spanish Village, a neighborhood near West Lake, who declined to give her name questioned how it could take so long to clean up the site.

“I’ll be dead and gone, but I’d like the place to be cleaned up even after we’re gone for the young people that might buy a house,” she said.

Karen Nickel, a co-founder of the activist group Just Moms STL, said the EPA’s plan to engage the community felt like a gut punch. She said it was an “insult” that after 10 years of activism by her and others, the EPA wanted to better communicate with residents.

Nickel said the EPA laughed at the activist group and claimed there was not radioactive waste except in the areas it had previously identified.

“The community’s breakdown in communications is on your end, not ours,” Nickel said.

Christen Commuso, community outreach specialist for the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, said activists pushed the EPA to do more testing to see if other parts of the site were radioactive.

“We begged you to do it,” Commuso said, adding that the EPA would respond that there was no historical information to back up the need for additional testing and aerial photos showed that the waste hadn’t shifted.

Commuso added: “Imagine, had you listened to us years prior, the lives that you could have potentially saved.”