Judith Landeros is 35 and has lived in Cicero for almost all of her life. Cicero’s rail yards, factories and warehouses — with names like Kropp Forge, Corey Steel and Koppers — have been around for so long that they seemingly blend in with the scenery. Growing up, she didn’t pay too much attention to the steel mills and heavy machinery that dot Laramie Avenue.

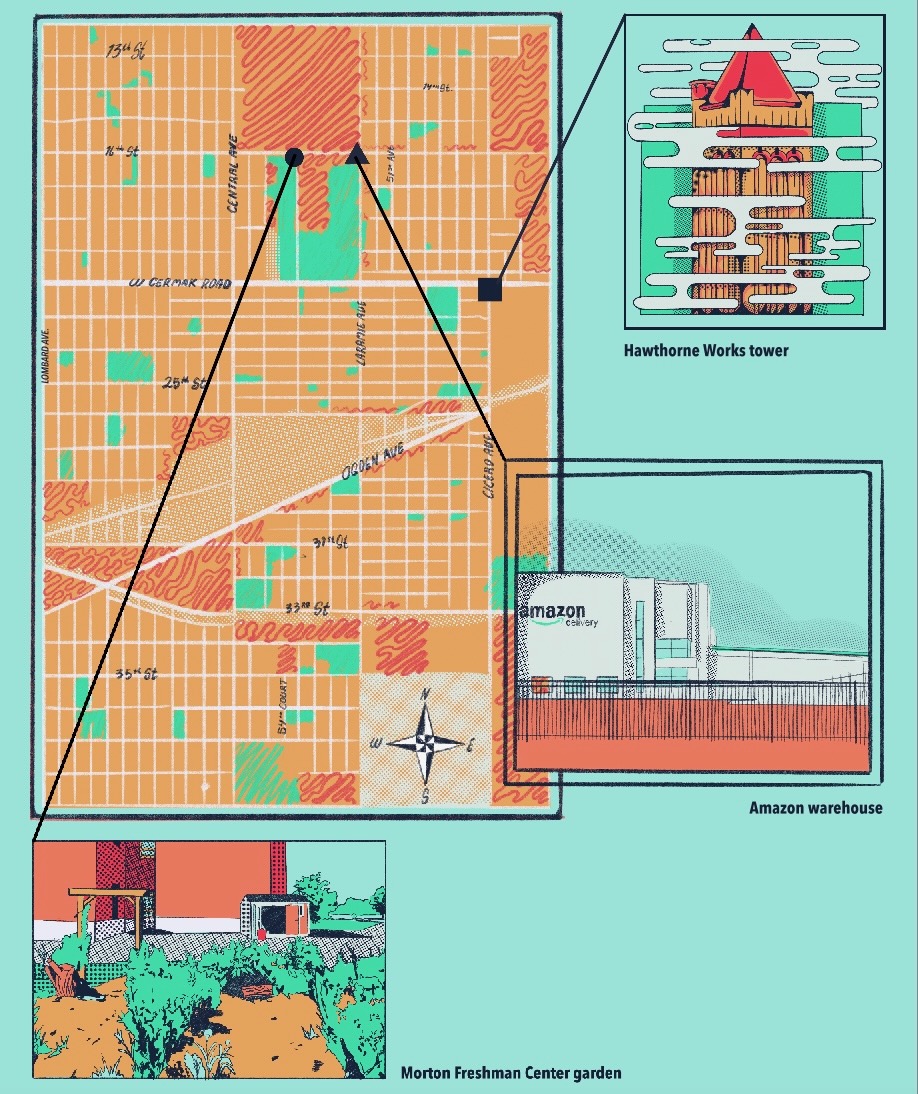

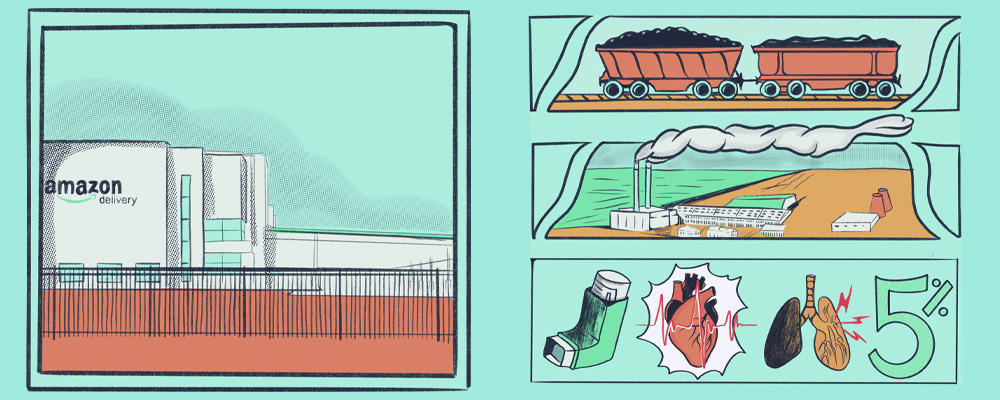

That all changed three years ago when Amazon took over a vacant lot and built two so-called “last-mile” fulfillment centers, totaling 1 million square feet of space, just a block from Landeros’s home — drawing the ire of environmentalists and residents who questioned why Amazon received millions of dollars in tax increment financing from the town in exchange for a promise of a few hundred jobs.

While air pollution isn’t new to Cicero, residents say, it’s beginning to feel worse. Mornings in the town are “dusty,” as Landeros describes it, and summers feel like “you can’t really see.”

“We never really ever get to talk about things like the air quality or the environment here in Cicero,” Landeros said last spring, while she sat on her front porch. “We’re aware of these things, but we don’t have actual data or facts to talk about it.”

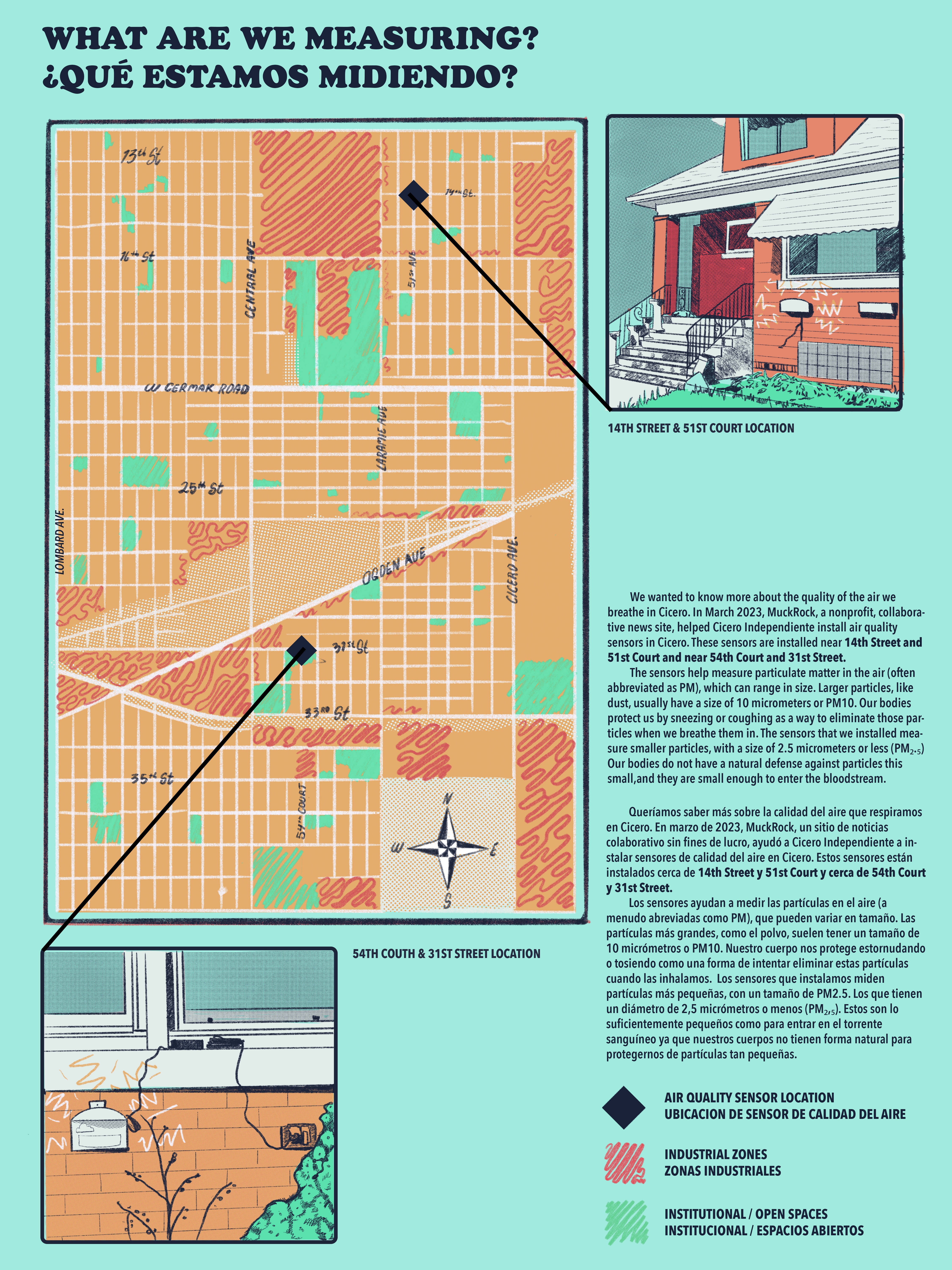

Now, a first-of-its-kind analysis of Cicero’s air quality, as part of a yearlong project involving sensors installed and monitored by the Cicero Independiente and MuckRock, shows the extent of daily air pollution here.

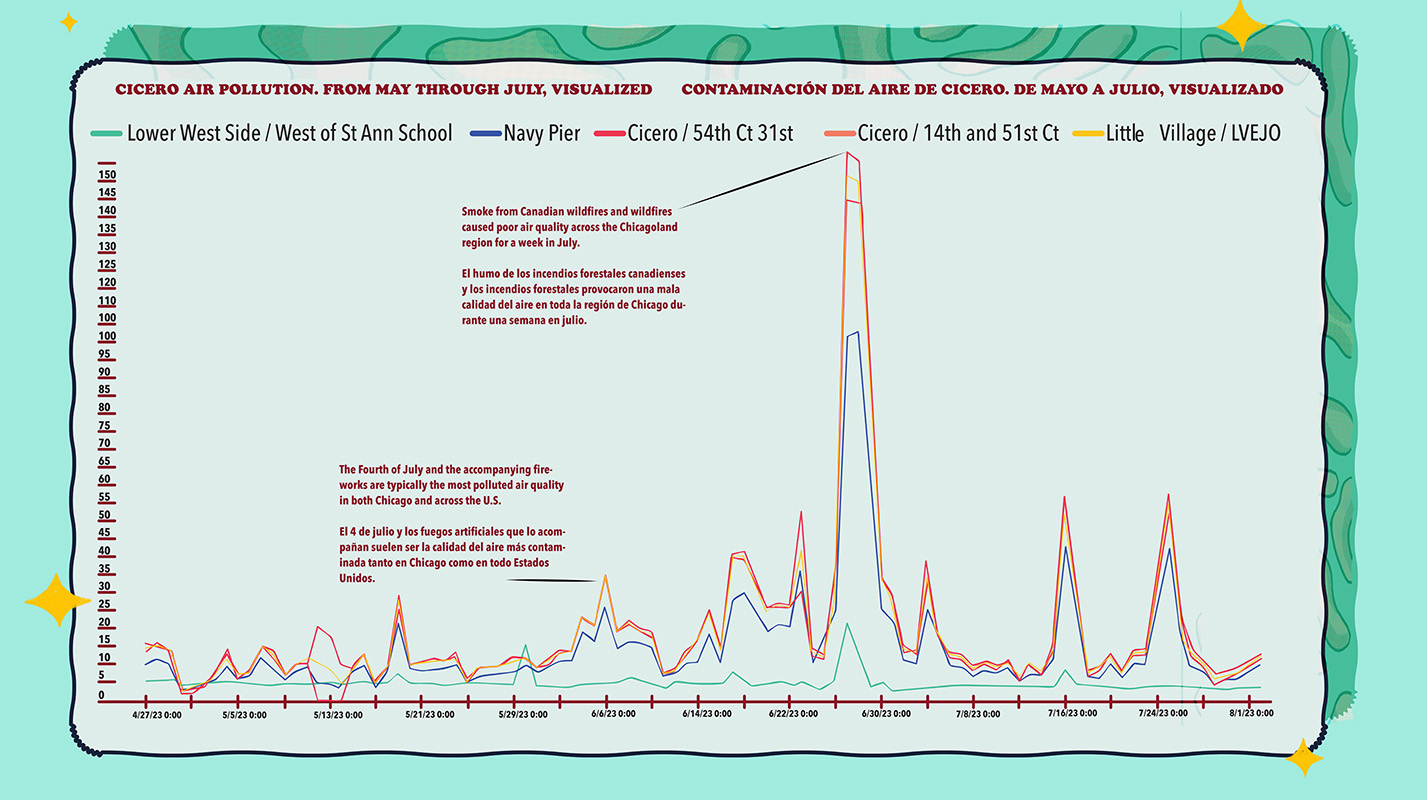

Poor air quality and pollution has been a persistent problem in Cicero and nearby Little Village for decades, with experts attributing it to Cicero’s century-long history of heavy industry, its residential density and a lack of parks and trees. But our sensor readings, first installed and recorded in April 2023 and tracked every day since, shows that Cicero’s air quality is markedly worse than places with other bustling industrial corridors in Chicagoland, such as the Lower West Side and Navy Pier.

The health effects of living in a place with decidedly poor air quality can be devastating and stretch across generations. Emissions from gas- and diesel-powered trains, trucks and machines include harmful pollutants: volatile organic materials, or VOM, which include cancer-causing compounds, like slightly sweet-smelling benzene, which has been linked to blood cancers and leukemia, and naphthalene, an insecticide used in mothballs; and black carbon, a particularly hazardous subset of fine particulate matter that is contributing to global warming. The two-story homes to the north of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe, or BNSF, rail yard have been found to have black carbon levels 30 to 104% higher than everyday levels, a landmark EPA study published in 2014 found.

In study after study, these pollutants have been found to increase the risk, and exacerbate cases, of cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, asthma and heart disease, said Marynia Kolak, a health geographer at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who led an air quality mapping project in the city of Chicago.

On particularly smoky days, Cicero is more prone to spikes in particulate matter, or PM₂.₅, otherwise known as soot, and black carbon, than other neighborhoods, the data shows. Even though Cicero rarely exceeds federal Clean Air Act standards for air quality, the data shows how bad the air can get. Black carbon is a common pollutant from diesel emissions and both the BNSF railyard and the Amazon facility loom large “in terms of the number of trucks passing through their gates” and the amount of emissions they produce, said Jesse McGrath, an environmental scientist who, as part of the EPA study published in 2014, analyzed pollution from the railyard. In terms of total diesel soot produced, the Cicero railyard ranks No. 4 out of 26 railyards in Cook County, according to the EPA’s AirToxScreen data released in 2019.

In 2021, the most recent year the Illinois EPA has released statewide air pollution data, Cicero violated the 8-hour threshold on ozone pollution just twice: on June 3 and Aug. 25, 2021, and the town didn’t record any violations of the 24-hour limit on particulate matter pollution.

But, according to data from our sensors, Cicero had at least nine days this summer — six days in June and three in July — where 24-hour averages were higher than the EPA’s daily threshold on soot. Those readings coincided with smoke blowing into the Midwest from Canada. And there were four other days in June and July with average, 24-hour readings near the federal limit of 35 micrograms.

Among our findings:

-

Cicero’s air quality is, at times, several times worse than less-industry-heavy neighborhoods in Chicagoland. On average, two of the Cicero sensors we installed showed readings of a little more than 18 PM₂.₅ each day, compared to just 4.8 PM₂.₅ for a comparable sensor on the Lower West Side and 14 PM₂.₅ at the Navy Pier. The Cicero readings were almost identical to those in Little Village, which successfully pushed to close its coal power plant in 2012.

-

On days of particularly bad air quality, such as during hot summer days or days filled with smoke from burning Canadian wildfires, Cicero’s air pollution gets even worse than other Cook County communities, the data shows. Spikes in air pollution can be seen around the Fourth of July, which is common because of fireworks and outdoor cookouts; in late June and early July, around the time of worsening smoke from the Canadian wildfires; and on July 16 and July 25, with the after-effects of the wildfires and particularly hot days, with temperatures in the 90s.

-

Our sensor network analysis shows that the EPA and a project tracking air quality by Microsoft don’t capture the amount of bad air pollution days in Cicero. From August 2022 to March 2023, Microsoft actively monitored air quality readings in nearby locations before abruptly shutting the Chicago-wide project down. It had one sensor in Cicero for a brief period as well; from those readings, 55% of days had daily average readings above 10 micrograms per cubic meter, which the EPA has proposed as its new maximum limit for annual emissions. The nearby EPA sensor, which captures particulate matter readings every six days, showed just 43% of the days exceeding the standard.

-

Cicero’s air quality is among the worst in Cook County, and the morning and evening rush hours, and Fridays, are particularly bad. Although sharing a similar trend with neighboring area Little Village and Near North side, Cicero’s corresponding PM₂.₅ increases were the greatest across all sensors. Comparatively high readings were seen in the early morning and late evening rush hour periods of 6 to 7 a.m. and 8 to 9 p.m., and there was a strong increase of PM₂.₅ levels on Fridays for two of our sensors. Most of the unusually high readings, or outliers, also appeared on Fridays.

In response to these findings, both the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency and the Cook County Department of Environment and Sustainability noted the especially poor air quality this summer was primarily a result of Canadian wildfires. Both agencies increased their public health messaging, to county and state residents. (Some residents who received the county alerts told the Independiente they were only in English, not Spanish, and couldn’t read them; the county did not respond to our request for comment about that complaint.) They also pointed to several newly-funded air pollution programs, from the federal American Rescue Plan Act.

But both agencies acknowledged gaps in how air pollution is monitored locally. The Illinois Ambient Air Monitoring Network, a collection of air quality monitoring sites across the state mandated by the federal Clean Air Act, has two locations in Cicero: one that tracks ozone and nitrogen oxides, the other for fine particulate matter. The Illinois EPA and Cook County are working to convert these filter-based monitors to stronger “federal equivalent method,” or FEM, monitors, which can allow for real-time reporting and more timely public health advisories.

There is no set timeline for converting to the better monitors, the Illinois EPA said, but the “goal is to convert them as soon as possible.”

Ray Hanania, the town of Cicero’s spokesperson, didn’t respond to requests for comment and, when approached at a biweekly town board meeting, promised to respond to our detailed questions, in writing, but never did. (Shortly after we requested comment from town officials, the board announced a free tree giveaway to residents.)

After reviewing the data, the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, or LVEJO, a nonprofit environmental justice group that successfully lobbied to close the coal-power Crawford Power Plant in 2012, said the readings “really emphasize that we do have the worst air quality” in the region.

“It means our community is mostly disregarded,” said Jocelyn Vazquez, a community science organizer for LVEJO, which uses similar monitors to track air quality.

Amazon representatives didn’t specifically respond to our questions about Cicero’s air pollution but a spokesperson, Kate Scarpa, provided a statement, saying, in part, that Amazon is “committed to becoming an even more sustainable company, and that includes how we show up in neighborhoods where our customers live, and employees work.” Amazon also pointed to its rollout of electric delivery vehicles, including hundreds of electric vans in Illinois, and a new renewable natural gas station it opened in Chicago last year.

BNSF Railway, which is the largest freight railroad company in the U.S., responded to our findings, saying it has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2030, and is on track through this year.

It also defended freight rail as the “cleanest, most environmentally friendly way to move goods over land,” and said it had no control over the trucks used to pick up containers at their yards. Those trucks, they argue, are procured by “third parties and under their control.”

“Despite these impressive figures, BNSF continues to strive for more,” BNSF said in its statement. “We invested in the exploratory development of a battery electric locomotive. We purchased electric cranes and hostlers to use in our rail yards and we are utilizing renewable diesel where available.”

Cicero’s long history with industrial polluters

Cicero has been a factory town since its founding, and it has no plans to change.

Since the turn of the 20th century, Cicero’s factories and plants have produced everything from General Electric stovetops and rubber stamps to steel pipe fittings and wood preservatives, said Jojo Galvan Mora, a curator at the Chicago History Museum who lived in Cicero for most of his life and is now pursuing a doctorate in history at Northwestern University. Like many factory towns, Cicero grew quickly in the industrial era of the 1920s and attracted a sizable migrant labor force.

But Cicero is also a small town, not a sprawling metropolis. It measures just two miles by three miles, from 46th Court to Lombard Avenue and Roosevelt to Pershing roads.

“We weren’t that big. Cicero was not Calumet, Cicero was not the Southeast Side,” Mora said. “And we just did not have the natural geography that’s important for the steel industry, in the way the Southeast Side did with the Calumet River and the Lake Michigan Harbor, feeding the electric power and the infrastructure for freight liners, bringing them the raw material needed to convert things into steel.”

Cicero also sits along one of the nation’s highest-volume freight corridors — the BNSF and Union Pacific rail yard — a busy confluence of rail lines, the Stevenson Expressway and the Chicago Sanitary & Ship Canal, which connects the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River.

There’s other types of industry, too. Chicago closed the last of its coal-fired power plants in 2012, but since then, delivery trucks and logistics facilities have sprouted up along the Interstate 55 corridor, taking over once-vacant plots of land.

Also tucked inside Cicero’s small land area are its residents living in single-family homes. Many are low-slung, brick bungalows and ranch-style houses built on narrow lots, constructed between the 1890s and 1950s. Many of these homes are in need of updating and aren’t equipped to handle heavy rains, like the flooding in Cicero in late June and early July that left some homes with up to 3 feet of water in their basements and resulted in a federal disaster declaration.

Cicero is a predominantly immigrant community of close to 85,000 residents; its demographic makeup underwent a dramatic change starting in the late 1980s, from a mostly Czech-speaking community to an enclave of first-generation Mexican and Central American immigrants. It’s now almost 88% Hispanic. Despite its reputation as a “sundown town” and a haven for mobsters and organized crime, Cicero now also has a growing Black population.

But due to its proximity to industry, limited green spaces, large immigrant population and higher levels of low-income earners, Cicero is categorized as “disadvantaged,” by the Council on Environmental Quality. That means poor air quality has an outsized effect in Cicero compared to other communities. On top of that, Cicero’s more vulnerable population is also more likely to be more susceptible to health problems, said Kolak of the University of Illinois.

In Cicero’s case, its residents are “both vulnerable and exposed,” Kolak said.

As the town notes in its comprehensive plan, roughly 25% of Cicero’s land is zoned for industrial-use. It’s largely centered along northern and southern portions of Cicero Avenue, the 54th Avenue industrial corridor at Roosevelt Road and along Ogden Avenue.

In that federal and state-funded plan from 2017, Cicero laid out an ambitious vision for growing its industrial sector, which at the time had a 5% vacancy rate of available land. To attract logistics facilities like Amazon, Cicero would rely on the concept of “Cargo Oriented Development” — by clustering businesses near railyards and skilled workers.

In that same 134-page document, feedback from town listening sessions were included, with several residents noting the town’s poor air quality. One unnamed participant was quoted as saying: “There are certain areas in Cicero where there is significant noise and air pollution — areas that need to be high priorities.”

What bad air quality does to human health, and what you can do about it

High levels of PM₂.₅ can lead to health issues like asthma, heart attack or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, otherwise known as COPD. An estimated 5% of all premature deaths in Chicago can be attributed to PM₂.₅.

Not everyone is impacted in the same way. Pregnant people, young children, the elderly and people who exercise outdoors are more likely to be affected when particulate matter levels are high.

Javier and Nathalie Garcia-Solis, and their 2-year-old son, “Jay-Jay,” live in Javier’s childhood home on South 54th Avenue. The lack of parks in Cicero and their close proximity to the busy freight railroad have long made them worry.

But now the steady stream of freight semi-trucks at all hours is a greater concern. “It’s busy at all times,” Nathalie said. Neither Javier or Nathalie have family histories of asthma but their son was diagnosed with asthma as an infant, and it oftentimes gets worse when the seasons change or when the local air quality index, or AQI, approaches “moderate” or “unhealthy” levels.

Earlier this month, Jay-Jay went to his pediatrician after a runny nose quickly turned into wheezing and heavy mucus. His parents put him into a hot bathroom, with the water running, to clear his nasal passages, and gave him two baths a day. He also has a nebulizer, a small machine that turns liquid medicine into a mist that can be inhaled.

But the nebulizer makes Jay-Jay uncomfortable so they turn it on while he sleeps, with his parents watching him in the dark, for a half-hour or longer. It’s an exhausting process — one repeated every time his asthma worsens.

The Garcia-Solis family run their own business, selling a non-alcoholic Michelada mix called “Big Mich” across the Chicagoland region, but, even with the product’s success, they can’t afford to move someplace with cleaner air.

“I would move if I could but we don’t make enough money to do that right now,” Nathalie said.

What you can do about Cicero’s air quality

There’s a few ways local residents can protect themselves during periods of especially bad air pollution, experts say. Identifying if you’re in a “high-risk group,” such as those with chronic heart or lung disease or diabetes, is an important first step. Those groups should take extra precautions to protect themselves on days with unhealthy air quality, according to the American Lung Association, such as reducing time spent outdoors to under 30 minutes; wearing a well-fitted N95 or KN95 mask; and, when indoors, keeping doors and windows shut and air conditioning recirculating.

Local governments can also take steps to improve air quality, like requiring an environmental impact study for new industrial businesses or creating a local air pollution control plan, which can include emission limits. States like California and Minnesota require environmental review studies to be submitted to local governments for certain projects and businesses. In Minnesota, some projects also have to submit an “air emissions risk analysis,” disclosing the risks a facility could have on the air in surrounding communities.

For its part, the town of Cicero has started a tree-planting program and a federally-funded project in the early 2000s restoring “brownfields,” or old industrial sites that require cleanup. But when we asked for any environmental impact reviews conducted for the Amazon facilities, the town said it didn’t have any. Many communities, like Cicero, don’t have special permitting or licensing requirements for facilities like Amazon’s, and there’s a push elsewhere to require companies and local governments to create new regulations, install air monitors and publish their findings.

“Cicero’s government has always been friendly to industry. And that’s a really big part of the draw to the town,” said Mora of Northwestern University. “But in some ways, it can also be seen as part of the issue. We get people jobs, but at what cost?”

Support for this project came from the Data-Driven Reporting Project, which is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University’s Medill School; the Rita Allen Foundation; the Reva and David Logan Foundation; the Healthy Communities Foundation; and the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri.

Reporting and writing for “The Air We Breathe” by Richie Requena for the Cicero Independiente, Luis Velazquez of the Cicero Independiente and Derek Kravitz and Dillon Bergin of MuckRock. Data analysis by Karen Wang and Dillon Bergin of MuckRock and Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation. Sensor installation by Sanjin Ibrahimovic of MuckRock. Graphics and illustrations by Brian Herrera for the Cicero Independiente and MuckRock and Kelly Kauffman of MuckRock. Editing by Derek Kravitz of MuckRock and April Alonso, Irene Romulo and Luis Velazquez of the Cicero Independiente.