Jessica Beverly made her two boys stay inside when Canadian wildfire smoke blanketed her Woodstock home in June. But she had work to do.

“I was busy in the garden but the smog and the sun blacked out the sky,” said Beverly, who lives on a 9-acre hobby farm 60 miles northwest of Chicago. “I just couldn’t breathe.’’

Her two horses and 30 chickens suffered, too, since she doesn’t have an indoor barn to clean the air for them. “They were very lethargic and required a lot of extra attention,’’ Beverly said.

On the worst days, according to her air quality monitor, the smoke mixed with Lake Michigan ozone to send Woodstock’s pollution levels higher than those in Chicago’s truck-choked Little Village.

At the same time, newspapers worldwide were running pictures showing Chicago’s lakefront almost wholly hidden in smoke.

In 2023, wildfire smoke from Canada helped smash pollution records all across the Midwest. When the numbers are finalized, the smoke could trigger a mandatory U.S. Environmental Protection Agency crackdown on pollution that experts say could slow economic growth.

Dozens of states and the EPA are so concerned they may exclude the smokiest days from the legally binding scorecards that determine whether they’re doing enough to fight pollution, according to a joint collaboration between the Tribune and the nonprofit news site MuckRock.

They could do so by invoking the so-called “exceptional events” exclusion for pollution humans don’t cause and can’t control. If they do, it could trigger the largest such exclusion in the history of the federal Clean Air Act.

The EPA began allowing the exclusions in 1977. But as wildfires fueled by climate change have become more frequent, more states have sought to classify them as exceptional.

Air quality agencies flagged 65 wildfire incidents as potential exceptional events in 2020, up from 19 in 2016, according to a previous analysis of EPA data acquired by MuckRock.

Since 2016, the EPA has approved exceptional events for areas that are home to at least 21 million Americans, according to a recent collaboration between MuckRock, the Guardian and a public radio consortium called The California Newsroom.

In 2023, dozens of states in the Midwest and beyond could band together to document how they were affected by the wildfires, said Zac Adelman, executive director of the Lake Michigan Air Directors Consortium.

They would hold public hearings and then use the joint research to support the separate applications they would file to the EPA for exceptional event exclusions.

The consortium coordinates air quality research and planning for Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Adelman backs regional exceptional event research as a way to prevent cash-strapped states from having to duplicate their efforts.

David Flannery, an attorney for a corporate coalition called the Midwest Ozone Group, said he has no doubt that more states will file more exceptional event claims as wildfires get more common, and that he supports them.

Midwest Ozone’s members include big companies like Cleveland Cliffs and ExxonMobil, which could face higher operating costs if the wildfires trigger an EPA crackdown.

Many environmentalists hate the whole idea.

“The fact is, wildfires are increasing and we’re going to see more pollution,” said Brian Urbaszewski, director of Chicago’s Respiratory Health Association.

“Writing them off as random and uncontrollable is undermining the goals of the Clean Air Act,” he said.

‘We will have to work very hard’

The numbers driving the debate are astonishing.

On July 25, one of the smokiest days, an EPA air monitor in Chicago recorded ozone concentrations 17% higher than the EPA standard, according to MuckRock’s analysis of publicly available EPA data.

In Elgin, an air monitor captured ozone levels 21% higher than the standard.

From Northbrook, up to Zion, Kenosha and Sheboygan, monitors recorded levels at about 30% or higher than the EPA standard on that day.

Ozone, an invisible, lung-scarring gas that contributes to smog, and tiny airborne particles known as PM2.5, already pose significant health threats in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland and other Midwest cities.

The wildfire smoke came with its own mix of particulates and ozone-causing chemicals, plus it magnified the impact they were already having on cities across the Midwest.

By Oct. 11, Muskegon, Michigan, had spent 54 days above the ozone level that triggers a mandatory EPA crackdown, according to Lake Michigan consortium records. This was the most for any city in the consortium’s six-state area.

Muskegon had spent 20 days above this so-called critical value in all of 2022, according to the records.

In several states across the Midwest, smoke pollution was so intense that local air agencies have already “flagged” or earmarked certain dates for possible exceptional event applications to the EPA, according to EPA data obtained by MuckRock.

From Cleveland, Ohio, to Madison, Wisconsin, to Clinton, Iowa, air agencies flagged monitors that registered daily averages of PM2.5 spiking at levels categorized as “very unhealthy,” by the EPA’s Air Quality Index.

Everyone is at risk for health effects under this ranking.

The Illinois EPA did not mark numbers for Chicago in this way but the city’s PM2.5 levels were listed as “very unhealthy” on June 28. That’s when they scored the highest reading all summer.

The agency plans to lower the limit for PM2.5 even further in the coming weeks because research has shown that diesel soot and other lung-penetrating particulates are much more lethal than previously thought.

PM2.5 can be emitted by factories, power plants, diesel and gasoline vehicles, residential fireplaces and wildfires.

Lower limits and more smoke will mean nothing but headaches for Illinois.

The state took 14 years to comply with the EPA’s 2008 limit for ozone.

The agency now lists Chicago and East St. Louis and parts of their neighboring states as moderate nonattainment for its 2015 limit.

Nearly three-quarters of all Illinois residents live in these noncompliant areas, according to the Sierra Club.

“The Illinois EPA is risk-averse,’’ Urbaszewski said. “They will only ask people to do what they have to ask, and that is no more than the federal government forces on them.’’

The wildfires, though, could force the EPA’s hand. They could compel the agency to bump Chicago and East St. Louis to a higher nonattainment level and, as a result, trigger tougher remedial actions.

Illinois compounded its problems in August by missing an initial EPA deadline for filing an improvement plan.

Until Illinois files a plan, it risks having the EPA impose one. The agency could freeze most of the state’s highway funds.

Kim Biggs, a spokeswoman for the Illinois EPA, said the state has another 18 months to file its improvement plan and expects to do so by then.

She said the state can decide whether to apply for exceptional events for 2023 only after the year’s numbers are complete.

In the meantime, she said, Illinois expanded its air quality alerts to include cities like Springfield, Peoria and East St. Louis, not just metropolitan Chicago.

Even if the state files an improvement plan, more wildfire smoke means the EPA could require Illinois to take additional steps to fight pollution.

The state might have to order small- and mid-sized factories in nonattainment areas to install the latest pollution controls.

The smoke could force Illinois to delay the permitting of new factories until the state identifies even bigger pollution savings from facilities that are closing or modernizing somewhere else.

John Kim, director of the Illinois EPA, declined through Biggs to comment.

Prior to being appointed to his post by Gov. J.B. Pritzker in 2019, Kim spent nearly three decades on the staff of the Illinois EPA and other state agencies.

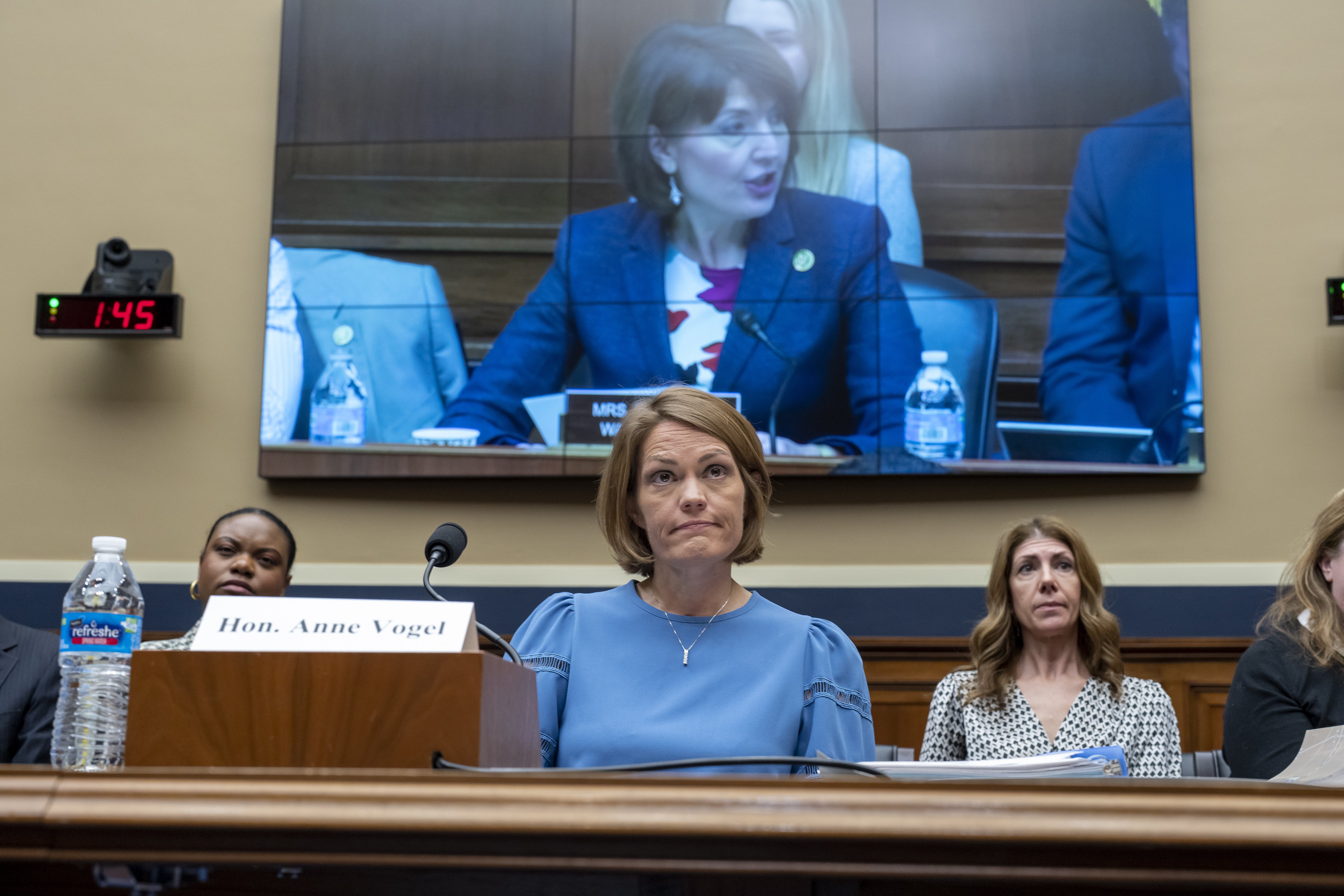

Ohio Governor Mike DeWine took a different approach and named one of his top personal aides as his environmental quarterback.

Prior to becoming director of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency in January, Anne Vogel was in charge of policy for DeWine and worked directly in his office.

In an interview about the wildfires, Vogel said, ``We certainly are getting out front of the messaging with our regulated entities.’’

She’s warning them already, she said, that the fires could bring stricter pollution controls.

For example, the smoke could force the EPA to bump the Cleveland area from a “moderate” to a “serious” nonattainment status for its eight-hour ozone limit.

This could require Cleveland to reduce the amount of driving by, for example, offering incentives for ride-sharing, telecommuting and mass transit.

“It will be a heavier lift for development,” Vogel said of the fires’ potential impact.

“It’s not a ‘no.’ We can still grow, and we can still have industrial development. But we will have to work very hard. It will be harder.”

Even though exceptional event declarations are becoming more common, they’re still hard to get. The applications can run hundreds of pages and cost $150,000 for staff time and consultants, according to the multi-newsroom “Smoke, Screened,” project published by The California Newsroom, MuckRock and the Guardian.

The EPA rejected Illinois’ effort to exclude certain days from its Cook County pollution records because of an Arizona wildfire in 2020.

In fact, the agency ruled smoke from that particular fire didn’t even reach Chicago.

In January, in contrast, the EPA approved an exceptional event application for two separate days at a single monitor on the east side of Detroit.

In 2022, smoke from a Canadian wildfire had pushed ozone readings from the monitor above the EPA’s safe, legal limit by a small amount, the agency found.

But even this small exceedance would have been enough to keep southeast Michigan in nonattainment status for the EPA’s safe, legal limit on ozone.

In turn, it could have triggered a mandatory vehicle inspection program for the region’s 4.8 million people.

Rather than focusing on such extensive reviews for one or two monitors, the EPA may accept research conducted jointly by several states on the 2023 Canadian wildfires, said John Mooney, air and radiation director of the EPA regional office in Chicago.

“It’s absolutely an option,” Mooney said. “It’s a good idea.”

Adelman, the consortium director, said he’s still determining how many states would join and for how many days.

This depends in part on how many are running close enough to EPA limits to allow the exclusion of certain smoke-filled days to bring them back into regulatory compliance.

But Adelman said it could be dozens of states, with most focusing on particulates and some on ozone.

The burden of proof shouldn’t be too high, he said, since nobody disputes that, on certain days last summer, Canadian wildfire smoke blanketed the eastern half of the United States.

“We’re quite certain that the wildfires in Canada had a significant severe impact on surface air quality,” Adelman said.

“We could smell it. It was reported on the news. It was very obvious.”

Congress established the EPA in 1970, with unanimous support in the Senate, to control traditional pollution sources like cars, steel mills and power plants.

The EPA’s response to multistate exceptional event research in 2023 could set a far-reaching precedent.

“We don’t think it’s our last summer like this,” Mooney said.

“Climate change, temperature, and weather patterns are all pointing to this maybe being more common in the future,” he said.

‘It looked like hell’

Jim Haywood, a staff meteorologist for the state of Michigan, is one of thousands of scientists laboring to understand what lies ahead.

When the smoke began gathering around his Grand Ledge home in May, he spent more time indoors, especially at sunset.

“It looked like hell outside because it was all red,” he said.

Then came June 28. It was his worst day in a quarter-century working for the state because of his 12-mile commute.

“It was like driving through a bog, a stinky, smelly bog,” Haywood said. “And my lungs hurt, even in a car with the air conditioner on trying to filter out that stuff.”

Once he got to the office, Haywood’s phones were ringing off the hook.

“We’d get calls asking to let Little Johnny go to his baseball game that night, and we were like, `absolutely not.’“

To understand why the 2023 fires were so lethal, it’s essential to start with the warming climate.

After the most significant temperature jump in at least eight decades, September 2023 was the warmest September in recorded history, according to NASA.

June, July and August combined were warmer than any other summer in NASA records.

And the heat fueled raging wildfires in such far flung places as Kazakhstan, Greece, Algeria, Chile, and the Canary Islands.

As things turned out, some of the heaviest burdens fell on Canada.

A helpful way to see this is to look at an animation produced by cartographer Peter Atwood and published in the Washington Post.

The animation depicts individual fires breaking out from coast to coast, not all at once but sporadically, like an old newsreel showing a B-52 bombing run over Vietnam.

Smoke plumes rise from many of the fires. Some are much thicker and presumably more lethal than others. Some reach far south into the United States and spin around like pinwheels.

What the animation lacks is a ground-level view.

This would have shown the fires towering over endangered towns as hundreds of thousands flee.

It would have shown them devouring 30 miles of forest a day with the aid of the hurricane-force winds they help generate.

It would have shown the fires leaping effortlessly over rivers and lakes long thought to present impregnable barriers.

All told, wildfires burned 45.5 million acres of Canada this year.

That’s bigger than the size of North Dakota and more than double the prior record, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre.

One consequence of having so many fires is that some occurred within a few hundred miles of Midwest population centers like Chicago.

This, in turn, meant that never before had so much smoke hugged the ground as it approached the city.

And as luck would have it, for much of the summer, one of the most persistent high-pressure areas in decades parked itself over the Great Lakes and refused to move.

“High pressure is like a blanket. It kind of puts a cap on everything and keeps it squished down near the ground,” Haywood said.

For much of the summer, an extended drought sucked the moisture out of trees. It suppressed the rainfall that flushes human pollutants from the sky.

Scientists say climate change is increasing the intensity, frequency and reach of Canadian wildfires.

Warming temperatures in the Arctic are slowing the jet stream, which are large winds that move along weather systems. This means endless droughts and, as a result, ideal conditions for wildfires in Canada’s northern forests to burn longer.

Many scientists also tie the hotter and drier weather in the United States and Canada last summer to a Pacific Ocean warming cycle called El Niño.

But the story is even more complicated.

One thing scientists are learning is that wildfire smoke gets more toxic the longer it stays aloft and the further it travels.

That’s because, as benign chemical components of the smoke fall away, toxic elements like benzene and formaldehyde become predominant, Haywood said.

That’s why many people complained, he said, that the smoke smelled like burning plastic.

Benzene and formaldehyde are classified as VOCs or volatile organic compounds.

Most VOCs are emitted from human activity, including making gasoline, petrochemicals, pesticides and cleaning supplies.

They’re the primary building block for ozone, along with nitrogen oxide or NOx, mainly from cars, steel mills and power plants.

Ozone forms when VOCs and NOx combine and get cooked by the sun.

And despite its pristine appearance, Lake Michigan is an ozone factory during the summer.

That’s because NOx and VOCs from Chicago mix together and then get “double-baked” as sunlight first pushes down through the atmosphere and then bounces back up from the lake’s mirror-like surface, Haywood said.

As the sun sets, late afternoon breezes drive the ozone onto the heavily populated shorelines around the lake.

All told, Wisconsin flagged data in 27 of its counties to potentially reference later in exceptional event requests and almost all the days between the first week of May and the end of June, according to state records obtained as part of the “Smoke, Screened,” project.

Michigan flagged 22 counties for elevated particulates and 13 for ozone on July 25 alone, according to the state’s response to a Tribune FOIA request.

Three other states — Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska — flagged 2023 data even though they haven’t filed an exceptional event application since the rule was modified in 2016, according to local and EPA records.

When answering a FOIA request identical to the one the Tribune filed with Michigan, the Illinois EPA said it had no response because it hasn’t flagged any 2023 wildfire data.

If these states want to band together for collective exceptional event research, they’ll have to decide soon, Adelman said.

They’ll need to hold public hearings next spring and submit their applications to the EPA in about a year.

The agency would reach a decision by 2025, around the time it also designates which areas have failed to comply with its upcoming reduction in particulate limits.

In the meantime, the agency could also impose “contingency measures” to boost air quality, said Hugh McDiarmid, Jr., spokesman for the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy.

These could include tighter pollution controls on factories and diesel trucks.

Adelman said he favors collective exceptional event research so that, instead of arguing with the EPA about the impact of smoke one fire at a time, they can spend their money in areas where they all need to improve.

These include putting tighter controls on VOCs and improving safeguards for Black and brown communities that suffer disproportionately from pollution, he said.

Another benefit of region wide exceptional event research could be to give scientists more time to study the fires.

Haywood said it’s too soon to say whether next summer will be as smoky as 2023.

“I relate last summer to a 100-year or 500-year flood where everything just came together ideally to make this happen,” Haywood said.

“It doesn’t mean it’s going to keep happening or that it will never happen,” he said. “It’s just a roll of the dice.”

‘Enough to protect us?’

Mary Nichols, the retired chair of the California Air Resources Board, said the EPA loosened its grip on exceptional event declarations two decades ago because of pressure from Western states then in the midst of an economic boom.

They saw pollution restrictions stemming from wildfires or dust storms as a direct threat to growth, Nichols said. They pushed back so hard, their Congressional delegations began making noise about reopening the entire Clean Air Act.

Despite the pressure, Nichols said she doesn’t believe the EPA has crossed any obvious legal or ethical lines with its approvals of exceptional events so far.

The agency wouldn’t automatically do so by accepting multistate research in 2023, said Nichols, who served as the agency’s assistant director for air and radiation from 1993 to 1997.

Nichols said she hopes, though, that this large-scale research would contribute to updated policies and even Clean Air Act amendments to respond to 21st-century challenges like wildfires.

These could include more cooperation with Canada and other countries on improved forest management policies, like the abolition of clear-cutting; better building regulations, such as requiring air filters in schools; and tough choices, like temporarily shutting down power lines during peak fire seasons even if they carry electricity from the wind or the sun.

“The question is whether the Clean Air Act is enough to protect us,” Nichols said. “The answer is ‘no, not without a lot more action.’“

Vogel, the director of the Ohio EPA, said she doesn’t know if she’d join multistate exceptional event research.

Either way, she said, Ohio will continue to clean its air.

For now, the state is in full or partial compliance with EPA limits on both particulates and (except for metropolitan Cleveland) ozone.

Two decades ago, all of Ohio’s big population centers were in nonattainment with the less-restrictive limit the EPA had on particulates at the time.

Ohio is using its payout from Volkswagen, which admitted in 2015 that it had cheated on emissions tests, to start getting diesel trucks off the road, Vogel said.

The state is chasing every federal dollar it can, she said, to promote solar power and cut greenhouse gasses.

In Ohio, these efforts are supported by Republicans and Democrats, in red and blue areas of the state, and by “sophisticated industry partners that know how the law works,” Vogel said.

This consensus will be sorely tested if Canada keeps burning and forces the EPA into mandatory crackdowns.

Even if the consensus bends, Vogel says, it won’t break.

“You know, for as much heat as we take sometimes as regulators, people also appreciate clean air.”

Beverly, the hobby farmer, is less optimistic.

What surprises her most about last summer’s wildfires, she said, is that America’s response was so blase.

“The health department issued alerts and the cities canceled some of their outdoor activities,” Beverly said. “But they just chalked it up to wildfires.

“There was no push for any policy changes to mitigate this in the future.”

Beverly, who volunteers with the Environmental Defenders of McHenry County, said the wildfires should raise new concerns about the county’s push for warehouse development.

If nothing else, she said, the county should require new warehouses to accept deliveries only from electric trucks and not ozone-causing diesels.

And the United States, she said, needs to spend more money on clean air.

“The EPA doesn’t have the staff for what they’re tasked with now,” Beverly said.

“If the wildfires mean more enforcement is needed, I’m concerned that they won’t be able to handle it.”

Photo credit: Jessica Beverly and her 8-year-old son, Teddy, feed chickens at their 9-acre hobby farm on Nov. 6, 2023, in Woodstock. “The health department issued alerts and the cities canceled some of their outdoor activities,” Beverly said. “But they just chalked it up to wildfires. There was no push for any policy changes to mitigate this in the future.” Photo by Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune