Cleaning up Coldwater Creek and other radioactive waste sites in St. Louis County will cost more than twice what federal officials thought six years ago, a new federal report finds.

A report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office released Tuesday finds the government’s financial liability at the sites ballooned from $177 million in 2016 to $406 million last year, primarily because of additional contamination that forced the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to expand the investigation and cleanup to include the creek’s 10-year floodplain.

The report takes to task the Army Corps, which is overseeing the cleanup of Coldwater Creek, a tributary of the Missouri River that has been contaminated for decades by radioactive waste leftover from the development of the first atomic bomb during World War II.

GAO auditors found the Army Corps didn’t sufficiently meet several best management practices, which could help prevent cost overruns or identify risks with cleanup projects. The Army Corps largely agreed with the findings of the report.

Tuesday’s report follows the GAO’s earlier findings that the U.S. government’s environmental liabilities pose a high risk.

“In our most recent high-risk list update, we found that departments and agencies, including the Department of Defense, need to take additional steps to monitor, report on and better understand their environmental liabilities,” the report says.

The GAO’s report focuses on sites within the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program, which was created in the 1970s to clean up areas contaminated in the course of the Manhattan Project, the name given to the World War II nuclear weapons program.

A monthslong investigation by The Missouri Independent, MuckRock and The Associated Press published earlier this year found radioactive waste was known to pose a threat to people living near Coldwater Creek as early as 1949, but federal officials repeatedly wrote potential risks off as “slight,” “minimal” or “low-level.”

St. Louis was pivotal to the Manhattan Project, resulting in a decades-long radioactive contamination problem. Uranium was refined in downtown St. Louis during the war, contaminating surrounding properties.

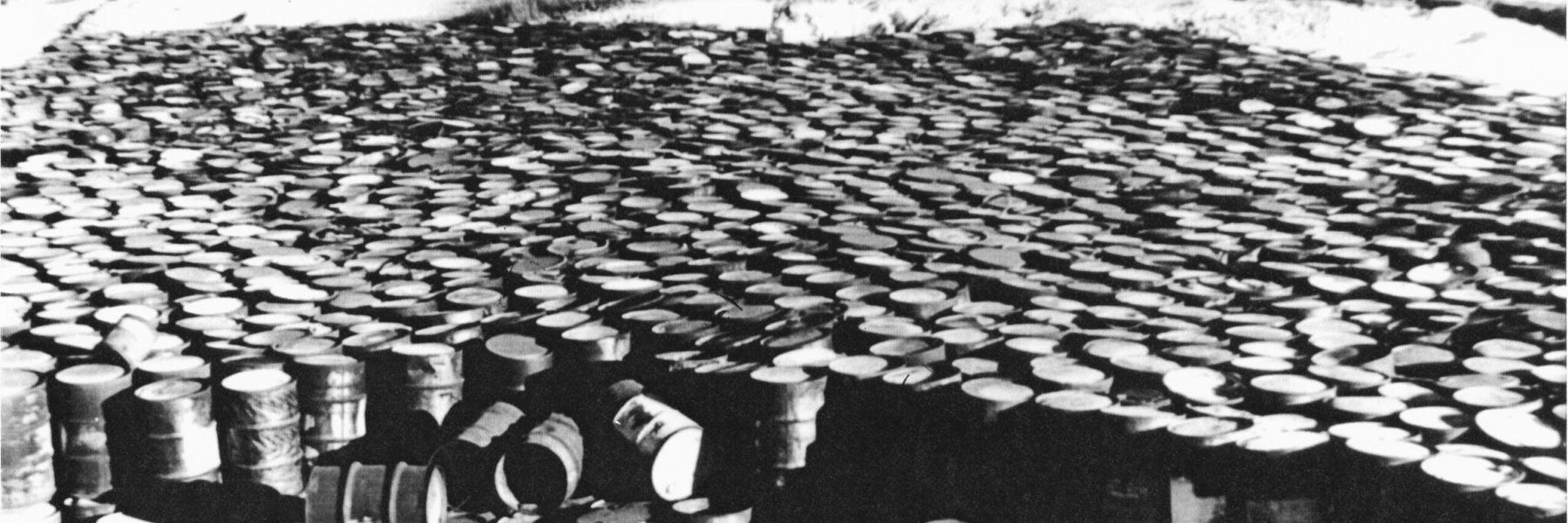

After the war, waste from the downtown site was trucked to St. Louis County, sometimes spilling along the way, and dumped at the airport. Decaying barrels released radioactive waste into Coldwater Creek, and despite acknowledging the risk of contamination, the private company that produced the waste thought it was too dangerous for workers to put the material in new barrels.

Eventually, the waste was sold to another private company and moved to a property on Latty Avenue, also adjacent to Coldwater Creek. The material was stored in the open where it could continue to contaminate the creek.

The Cotter Corp., which purchased the waste to extract valuable metals, dried and shipped most of it to its facility in Colorado before dumping the rest in the West Lake Landfill, where it remains today.

The Army Corps has authority through FUSRAP over the downtown, Coldwater Creek, airport and Latty Avenue sites, but cleanup of the landfill is being overseen by the Environmental Protection Agency.

U.S. Rep. Cori Bush, D-St. Louis, requested the GAO investigate the Army Corps stewardship of the sites in 2021. She noted in a statement that the report found the St. Louis sites are near some of the most underserved communities compared to other FUSRAP sites.

“The federal government bears full responsibility for ensuring that this waste is expeditiously cleaned up and that all those harmed are made whole,” Bush said in a statement.

The Army Corps’ liability at the downtown site where Mallinckrodt Chemical Works refined uranium during World War II also rose precipitously.

The GAO report evaluated the cleanup efforts and costs at 19 FUSRAP sites spread across eight states, totaling $2.6 billion in environmental liabilities. Four of those sites make up about 75% of that total amount: the North St. Louis County sites; the Niagara Falls Storage Site in New York; the Shallow Land Disposal Area, in Parks Township, Pa., outside Pittsburgh; and Guterl Specialty Steel, also in Niagara County, N.Y.

These four sites generally require complex cleanup work or cover large areas; for example, the Niagara Falls Storage Site has several types of buried radioactive waste that will be exhumed, packaged and shipped to an offsite location, officials say. In addition, eight of the 19 sites are within or adjacent to underserved racial or ethnic populations or have high rates of poverty compared with the rest of the county where they are located.

All told, the liability estimate for all 19 sites has grown by nearly $1 billion, or roughly 63%, over the past seven years, the GAO found.

Downtown St. Louis and North St. Louis County among the most difficult cleanup sites in the U.S.

For years, contaminated soil at the downtown site wasn’t accessible to the Army Corps, the report says, because it was under a building that was in use by the property owner. The owner of the site decided to grant access, and the Corps found it had additional cleanup work to do, increasing the liability for the site from $17 million to $96 million within a year.

The GAO also found the Army Corps sites in St. Louis city and county are all situated in underserved communities.

While 53% of the residents of St. Louis are from underserved racial or ethnic groups, the report says, 80% of individuals near the downtown Mallinckrodt site are. The area’s poverty rate is 1.5 times higher than the rest of the city.

In St. Louis County, 29% of residents are from underserved groups compared to 63% of residents near the radioactive sites. Like downtown, the area suffers from a poverty rate 1.5 times the rest of the county.

The Government Accountability Office found the Army Corps could benefit from better management practices, including a risk management program.

While Army Corps conducts risk management operations on individual projects, the GAO found it doesn’t have a risk management plan for the Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program as a whole. Doing so could help it more efficiently allocate resources, the report says.

“Furthermore, better risk management could help the Corps plan for uncertainties, such as the discovery of more contamination requiring cleanup, that may affect future environmental liability,” the GAO says.

The report says a risk management program could also identify potential opportunities affecting the entire program. The report gives, as an example, the $182 million the Army Corps received in appropriations but hasn’t spent because of its limited staffing.

In a response included in the report, the U.S. Department of Defense largely concurred with the GAO’s recommendations and said it would work with the Army to implement several management practices.

Bush said the report shows the Army Corps is “leaving money on the table as a result of mismanagement” and needs to build trust and improve communication with the community.

“This report validates concerns people have been raising for years,” Bush said. “The Corps must heed their recommendations without delay.”

Congressman Jamie Raskin, D-Maryland, ranking member on the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, said in a statement that the long delay in remediating Manhattan Project sites is “unconscionable.”

“Decades after the federal government generated large amounts of toxic nuclear waste as a result of nuclear weapons production,” Raskin said, “America’s most underserved communities still bear the brunt of deadly contamination from one of the most significant environmental disasters in our nation’s history.”

Photo credits: State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection, 1943-2006 and Theo Welling/Riverfront Times.