WASHINGTON — Victims of nuclear contamination rallied in the nation’s capital on Wednesday in support of bipartisan legislation that would extend compensation for those harmed by radioactive waste.

U.S. Sens. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, and Ben Ray Luján, a New Mexico Democrat, held a rally and press conference outside the U.S. Capitol as part of their efforts to advance legislation to extend coverage from the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA, program.

People from New Mexico, Utah and Missouri, including Just Moms STL advocates and others from St. Louis who had been harmed by nuclear contamination, joined the event.

Hawley sponsored an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act that the Senate adopted in July. The defense bill, which is not yet finalized, authorizes Department of Defense policy for the next fiscal year.

This amendment extends the RECA program to include people in St. Louis who were affected by improperly stored Manhattan Project waste. The Manhattan Project was the U.S. nuclear weapons development program in the 1940s that created the atomic bomb.

An investigation earlier this year by The Missouri Independent and MuckRock found that, for decades, private companies and federal agencies knew the haphazardly handled waste posed a risk to human health and the environment but downplayed it.

Following World War II, uranium refined in downtown St. Louis was dumped, uncovered, at the city’s airport. Chunks of radioactive waste fell from trucks on the road from the processing facility to St. Louis County.

Once at the airport, the wind and rainwater carried the waste into Coldwater Creek, which won’t be fully remediated for another 15 years.

“If a government is going to create a disaster, the government should clean it up,” Hawley said.

Hawley said it is the responsibility of the federal government to “pay the bills of the men and women who have gotten sick,” and to “pay the survivor benefits of those who have been lost.”

“The government used the city of St. Louis as a uranium processing facility as a major site, and then when that was over, what did it do? Did it take care of the waste? No,” Hawley said. “It allowed it to seep into the groundwater. It allowed it to get into Coldwater Creek. It allowed it to get into the soil.”

Hawley referenced high breast cancer and childhood brain tumor rates in St. Louis, and said it’s not a coincidence.

“Generations of Missourians, children, were poisoned because of the government’s negligence,” Hawley said.

Expansion of RECA

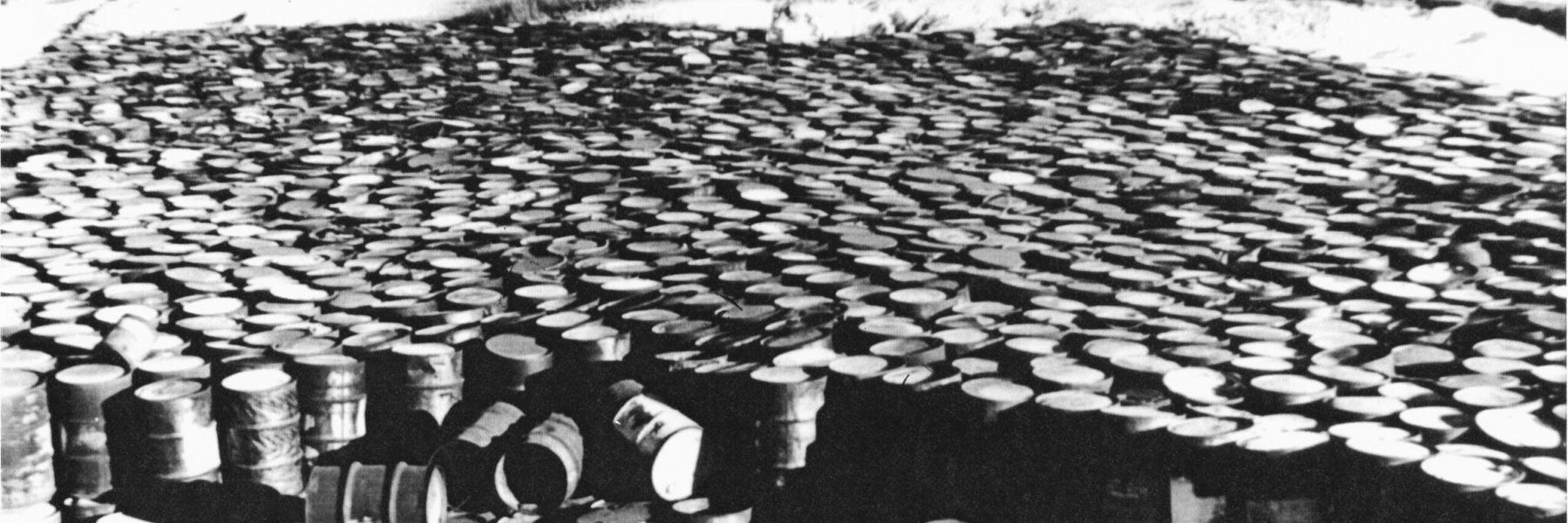

A photo taken in 1960 of deteriorating steel drums containing radioactive residues near Coldwater Creek, by the Mallinckrodt-St. Louis Sites Task Force Working Group (State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection, 1943-2006).

A photo taken in 1960 of deteriorating steel drums containing radioactive residues near Coldwater Creek, by the Mallinckrodt-St. Louis Sites Task Force Working Group (State Historical Society of Missouri, Kay Drey Mallinckrodt Collection, 1943-2006).

Expanding the compensation program would allow individuals in ZIP codes affected by the waste to receive compensation if they suffer from certain cancers or diseases.

RECA coverage would also be extended to New Mexico “downwinders,” who lived downwind of the bomb’s testing site in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and post-1971 uranium miners.

Colorado, Idaho, Montana and Guam would also be given coverage under the amendment, with coverage expanded to areas in Nevada, Utah and Arizona not already included.

“Justice is not complete until it is justice for all, and that is what we are asking for — justice for everybody who was hurt in the mining,” said U.S. Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez, a New Mexico Democrat who spoke at the event.

Hawley, Luján and U.S. Sen. Mike Crapo, an Idaho Republican, worked in a bipartisan effort to get the amendment included in the defense authorization bill, which still must be negotiated by the House and Senate.

The RECA program is currently due to sunset in 2024, but Hawley’s amendment would extend the program for an additional 19 years once enacted, according to a press release.

Hawley and Luján said they are optimistic and hopeful that the amendment will be included in the final version of the defense policy bill.

“Senators, you did an amazing thing,” Fernandez told Hawley and Luján. “I saw you working. I saw all of you working on the floor. We were watching, and we were crying. We were crying out of pride, and the idea that this is the moment, this is the historical moment when this will finally get done.”

Lasting impact on Navajo Nation

Crystalyne Curley, speaker of the Navajo Nation Council, said there is a debt owed to Navajo uranium workers. She said from 1944 to 1986, nearly 300 million tons of uranium was extracted from Navajo Nation.

Curley said the government failed to adequately communicate with Navajo uranium workers and neglected to translate the risks associated with the exposure to radiation. This has led to generations of illnesses and deaths across Navajo communities, Curley said.

Curley told the audience about Leslie Begay, one of the victims, who was sitting in a wheelchair near her. Begay served in the Marine Corps and mined uranium, she said, “and he was rewarded with disease and near-death experiences.”

Curley said Begay struggled to access the medical treatment he needed, as he was turned away from the Indian Health Service and Department of Veterans Affairs. Begay was eventually able to receive a double lung transplant, Curley said.

Luján spoke about his father, who worked in Los Alamos and died from lung cancer linked to nuclear contamination.

“While it (the cancer) had spread, he believed that he needed stronger lungs, and he would tell us, ‘Lend me your breath,’” Luján said, choking up.

“You’re lending your breath to many people,” Luján told Begay.

Phil Harrison, a former uranium miner, also spoke at the event. He is a founder of the Navajo Uranium Radiation Victims’ Committee, which helped to first get RECA passed in 1990.

Harrison said his father died from lung cancer when he was 43 years old. Harrison’s own kidneys failed, he said.

“I thought I just had a mosquito bite, rash all over my body,” Harrison said.

He said he drank water in the mine while working his eight-hour shifts. He said no one had told him about the potential safety risks of his actions.

Harrison said the Navajo miners “couldn’t read and write and understand.” They “were given a shovel simply to feed their families, put food and clothes on the table,” Harrison said.

“We protected national security, so you all can have freedom,” Harrison said.

New Mexico and Utah downwinders

Tina Cordova, co-founder of Tularosa Basin Downwinders Conservation, said she represents the people who lived “as close as 12 miles to where they detonated the first bomb in the desert of New Mexico.”

New Mexico residents who suffered after the first atomic bomb was detonated at a test site 200 miles from the laboratory in Los Alamos still haven’t been compensated.

The first atomic bomb was detonated in the Tularosa Basin in July 1945 with no warning to residents.

The “downwinders” in New Mexico still aren’t eligible for compensation offered to residents downwind of another test site in Nevada. Residents downwind of that site in parts of Nevada, Utah and New Mexico can receive a payment of up to $50,000.

“They didn’t have the decency to let us know that as that ash fell from the sky for days afterwards, that it would completely contaminate our water supply,” Cordova said.

She said she is the fourth generation in her family to have cancer since 1945.

“And this is what a fifth generation looks like,” Cordova said, and held up a photograph of her 23-year-old niece who has been diagnosed with thyroid cancer.

Cordova was diagnosed with thyroid cancer when she was 39, she said.

“This is the legacy of the nuclear development and testing that took place in our country during the Cold War and before, and it is time for justice,” Cordova said.

Mary Dickson, a “downwinder” from Salt Lake City, Utah, said she and other nuclear contamination victims are the legacy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, who is often called the “father of the atomic bomb.”

Dickson, who had thyroid cancer and had a hysterectomy due to tumors, said two of her sisters were also diagnosed with cancers. Dickson’s older sister died from cancer, and her niece has thyroid cancer.

She said 54 people from her neighborhood in Salt Lake City have had different cancers, tumors or illnesses related to radiation.

“When we hear that we must be fiscally responsible, I ask you, what is the life of my sister worth?” Dickson said. “What are the lives of your families worth? There can be no amount that can make up for their lives.”

Dickson said this struggle is “not just physical, it’s emotional, it’s financial.”

“Every time I feel a lump, every time I get sick, I worry that it’s happening again,” Dickson said.

Protecting St. Louis

Karen Nickel, left, and Dawn Chapman flip through binders full of government documents about St. Louis County sites contaminated by nuclear waste left over from World War II. Nickel and Chapman founded Just Moms STL to advocate for the community to federal environmental and energy officials (Theo Welling/Riverfront Times).

Karen Nickel, left, and Dawn Chapman flip through binders full of government documents about St. Louis County sites contaminated by nuclear waste left over from World War II. Nickel and Chapman founded Just Moms STL to advocate for the community to federal environmental and energy officials (Theo Welling/Riverfront Times).

Dawn Chapman, co-founder of Just Moms STL, an organization aiming to protect people from further exposure to radioactive waste from the atomic bomb, said they were not “asking for a handout.”

“We’re asking for the extension of a program that’s already in existence,” Chapman said. “And we’re asking for people to be included, who frankly this program was created for — and why in the world they were left out of it, I have no idea.”

Hawley said that everyone is affected by this issue and “this ought to be something that everybody can get behind.”

“We need to get out there and make sure that we start testing the people in St. Louis and throughout Missouri who were exposed so we can save their lives,” Fernandez said.

Hawley said 301 dump truckloads of radioactive waste have been carted out near Jana Elementary School in Florissant, Missouri. The school was shut down in October 2022 following signs of radioactivity on the property.

“Just two months ago, they were telling us there is no radioactive waste nearby, no reason to be concerned,” Hawley said. “Now they are carting it out, and they’re also telling the community, though, ‘You’re just going to have to live with it, we’re not going to reopen the school.’”

The school needs to be cleaned up and reopened, Hawley said.

Allison Kite of The Missouri Independent contributed to this report.