Local governments in the St. Louis area could request radioactive waste testing from the state under a Missouri House bill that would appropriate money to a long-unfunded program.

The Missouri House Conservation and Natural Resources Committee on Monday heard testimony on a bill that would transfer $300,000 to a radioactive waste investigations fund created six years ago.

Despite the fund passing the legislature in 2018 and being signed into law by Gov. Mike Parson, it has never had any money allocated to it.

The funding — double what Parson recommended in his proposed budget — would allow the state to test sites that are feared to be contaminated with decades-old radioactive waste.

“Legacy waste from the Manhattan Project has been bought, resold, moved around the area, leaving in its path radioactive contamination to the extent that we don’t necessarily know every single last place that it still exists,” said state Rep. Mark Matthiesen, an O’Fallon Republican.

The committee took no action on the bill Monday evening.

Federal agencies are working to clean up several sites, but Matthiesen said the fund would allow state environmental regulators to identify nearby residential areas that could be contaminated.

“There’s many areas where we have known contamination but there could potentially be some areas surrounding those known areas where there could still be contamination that is yet to be identified,” he said.

The St. Louis area has struggled for decades with remnant radioactive waste from World War II. The city was integral to the Manhattan Project, the name given to the war-ear effort to build the world’s first atomic bomb. Waste from uranium refining efforts in downtown St. Louis was transported to several sites in St. Louis and St. Charles counties, contaminating parks, lakes and Coldwater Creek.

Parts of the region aren’t expected to be remediated until 2038 — 93 years after the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and almost 90 years after the waste was identified as a risk to Coldwater Creek.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is remediating Coldwater Creek, which runs through what are now busy suburbs. It was contaminated in the years after World War II when radioactive waste was dumped at the nearby St. Louis airport and at a property in Hazelwood.

For decades, the contaminated creek water exposed residents to radioactive waste. A federal study found the creek contamination raised the risk of certain cancers for people who lived nearby and children played in the creek.

From the airport, the radioactive waste was sold and moved to Hazelwood where it again sat next to and leaked into Coldwater Creek. The Cotter Corporation, which bought the waste to extract valuable metals, then requested to dump the remaining waste that had no economic value at a quarry in Weldon Spring or bury it onsite. When the federal government denied the company permission, it illegally dumped the waste at the West Lake Landfill where it remains today.

The Environmental Protection Agency is leading the effort to design a remediation for the landfill.

The decades-long problem has come under new scrutiny as the EPA works to start remediation at West Lake and an outside expert identified contamination at an elementary school next to Coldwater Creek.

The Missouri Independent, in partnership with MuckRock and the Associated Press, revealed last summer that federal officials and companies that handled the waste knew the radioactive waste posed a risk to St. Louis-area residents for years before making it known to the public.

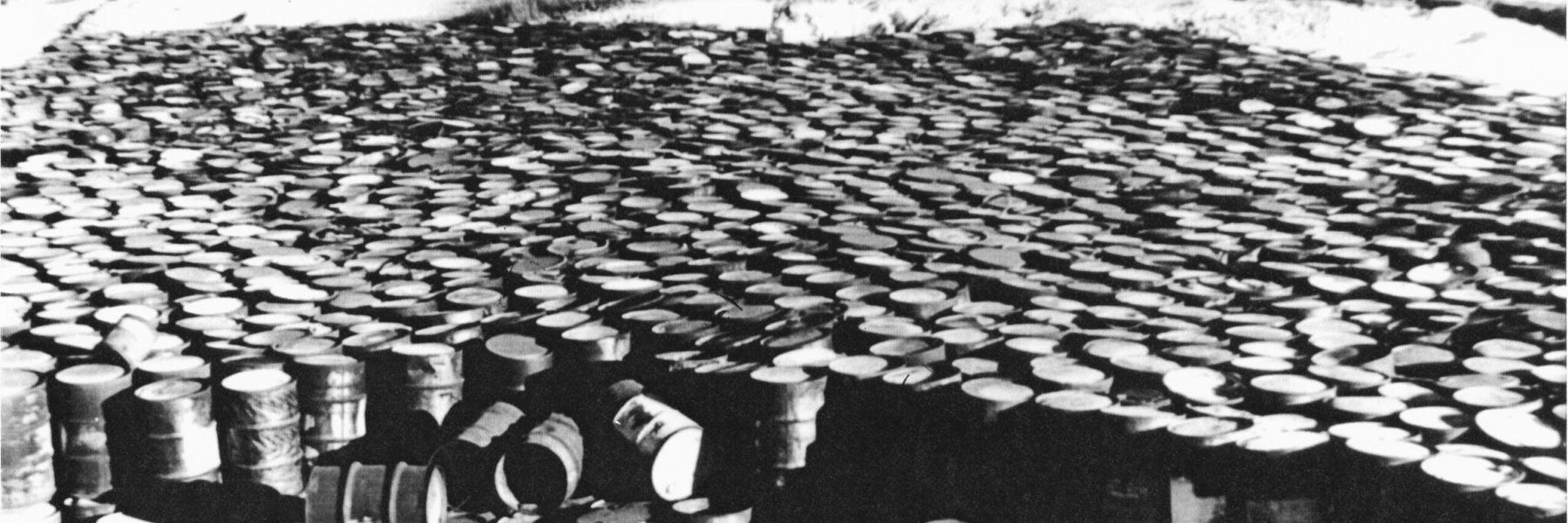

In 1949, Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, which refined uranium in downtown St. Louis for the Manhattan Project, realized waste stored in decaying steel drums at the airport threatened to leak into Coldwater Creek. It determined that workers couldn’t move the material to new containers because “the hazards to the workers involved in such an occupation would be considerable.”

But despite knowing the waste was spreading, federal officials downplayed the risks for years.

State Rep. Paula Brown, a Democrat from Hazelwood, noted despite the EPA reaching a decision on how to handle the West Lake Landfill, “there is still no shovel in the ground.” She noted activists for years told the EPA the agency didn’t have a handle on where all of the radioactive waste was and urged further testing of the landfill.

“They kept saying, ‘No, it’s not. No it’s not,’” Brown said. “Well, they have found it. It is awful…so this is an important bill.”