For years, the Koppers coal tar plant in Cicero has been the town’s biggest source of industrial air pollution. In the neighborhoods near the 36-acre facility, some residents say they have always noticed white smoke billowing from its smokestacks, rotten smells and poor air quality.

They say it’s worse in the summer, causing headaches and nausea, and is often so bad that they have to stay indoors and close their windows — even if many residents don’t know what Koppers is or what they make.

Now, an investigation by two nonprofit newsrooms, the Cicero Independiente and MuckRock, shows how the 101-year-old Koppers plant is not only one of the single largest polluters of toxic and cancer-linked chemicals in the U.S. It has also routinely been found in violation of both state and federal environmental laws dating back 50 years — from the late 1970s until this past summer.

Among the findings, which rely on Illinois and federal Environmental Protection Agency pollution data, interviews with Cicero residents, environmental and medical experts and a review of local, state and federal regulatory records obtained through open-records requests and the Freedom of Information Act:

- This October, the Illinois EPA sent Koppers a set of 25 alleged violations of state and federal environmental laws and is awaiting a response from the company. The notice, obtained through an open-records request to the Illinois EPA, shows the plant released excess “volatile organic material” — gases that can cause short-term and chronic health problems — unchecked into the atmosphere over an entire year, between the summer of 2022 and the summer of 2023.

-

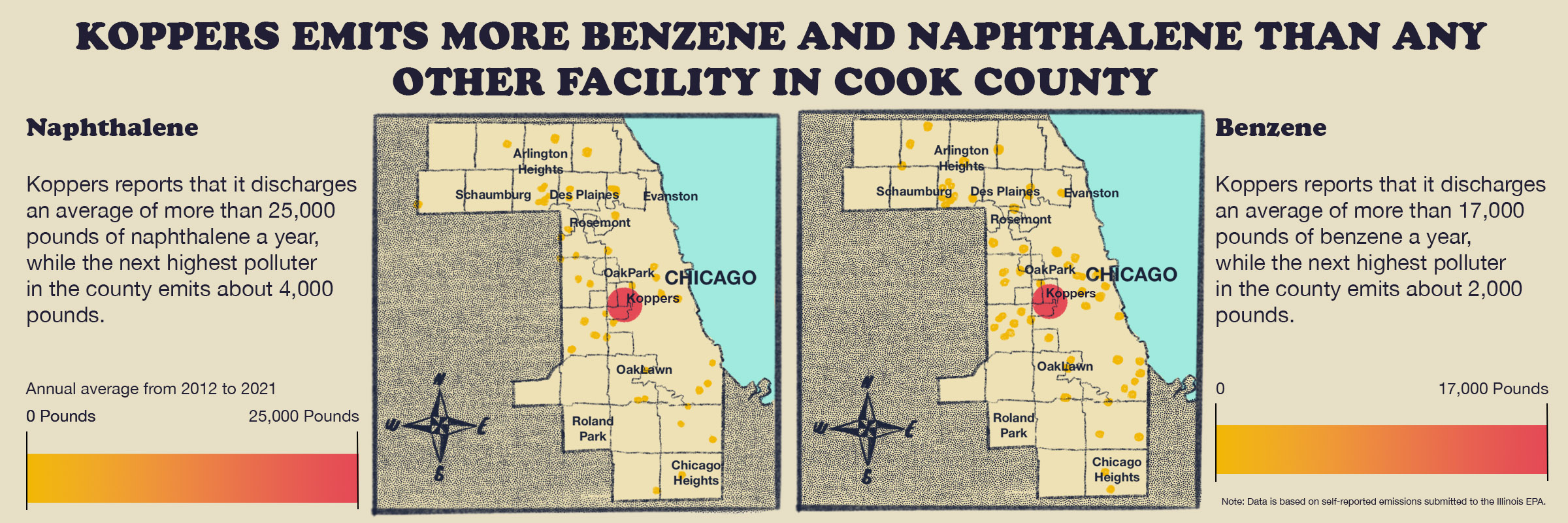

Koppers pollutes more of two types of these volatile organic materials — benzene and naphthalene — than any other polluter in Cook County, according to a MuckRock and Independiente analysis of emissions inventory data obtained through an open-records request to Illinois EPA.

-

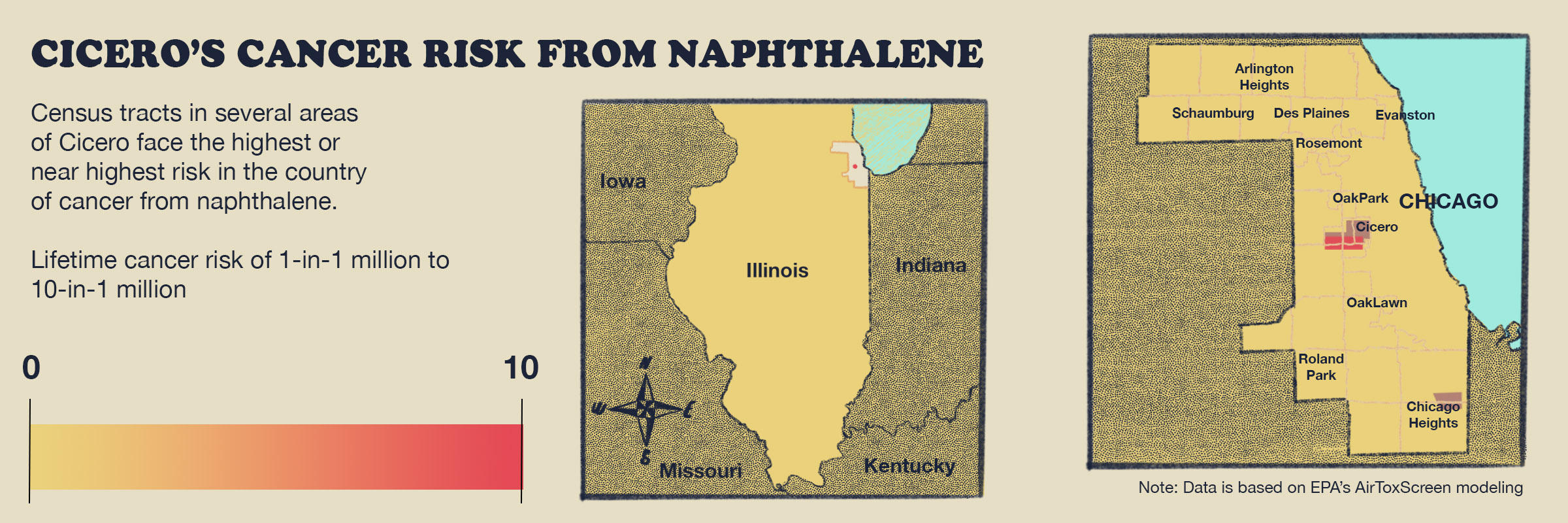

Nationally, Koppers ranks in the top 15% of facilities that emit benzene and top 3% of those that release naphthalene, out of more than 1,000 facilities that report these emissions in the federal EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory. EPA risk modeling based on emissions data places several census tracts in Cicero at a higher risk of cancer from naphthalene than in almost anywhere else in the country.

-

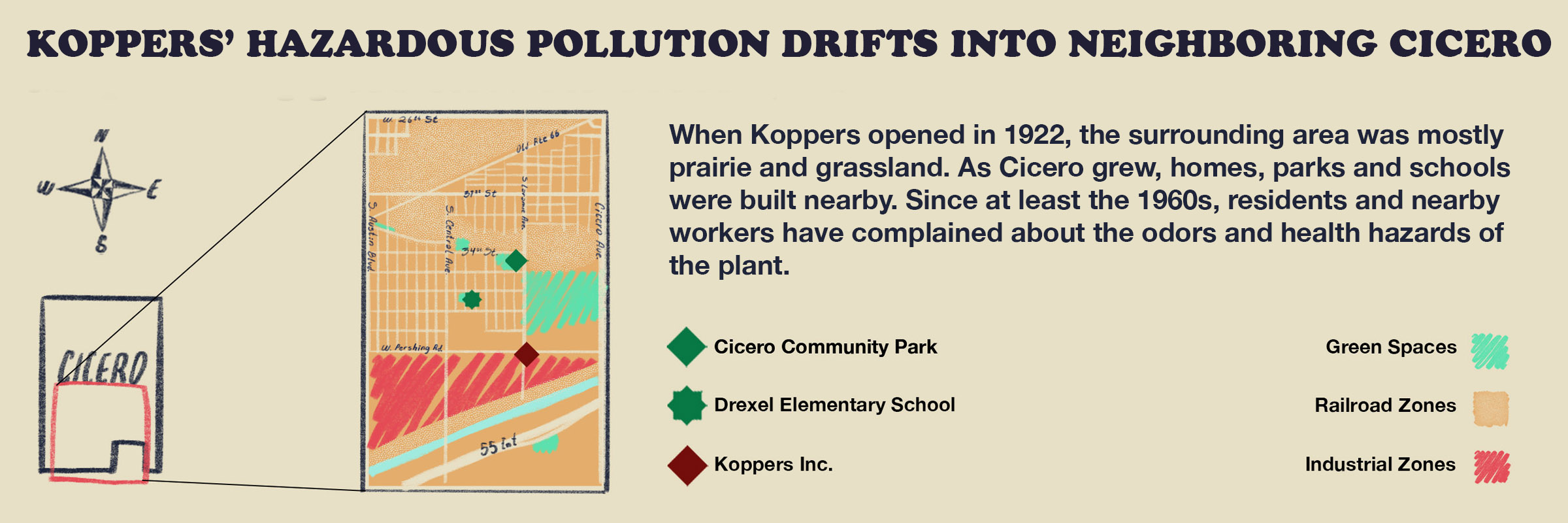

Any exposure to cancer-causing chemicals raises the risk of contracting cancer and the amount of pollution spewing from Koppers could have already been enough to put some members of the community at risk, especially children and other vulnerable groups, experts say. An elementary school, an early childhood center, a community park and hundreds of homes are situated within a half of a mile of the plant.

-

The new violations suggest that the plant was polluting over what it was allowed to and are just the latest of three other violation notices from the Illinois EPA in recent years. The plant also received one in 2020 and two in 2021.

Both the number and scope of the most recent alleged Koppers violations are rare, said Dr. Peter Orris, chief of occupational and environmental medicine at the University of Illinois Hospital. “This is a plant that would cause me considerable concern and you want to see what they do to clean it up,” Orris said in an interview.

The Illinois EPA said in a statement that it will review a formal response from Koppers before taking any possible action, which could include fines and a civil suit. The agency said it doesn’t comment on pending compliance or enforcement actions. The Illinois Attorney General’s Office, which handles both civil and criminal litigation of environmental crimes, said that before the October violations, it had already received two referrals regarding Koppers from the state EPA but declined to comment further.

Koppers sits on the south side of Pershing Road, on the border between the 85,000-resident town of Cicero and the 7,500-person village of Stickney. Stickney’s mayor, Jeff Walik, said in a statement that it would defer to county, state and federal agencies for enforcement of environmental regulations. But he said the village would encourage those agencies to “be vigilant in their protection of the environment, the residents of Stickney and the region.”

The superintendent of Cicero School District 99, Aldo Calderin, said in a statement that district leaders are aware of the alleged pollution violations by Koppers, calling the plant part of a “necessary” industry. “We are confident that the Illinois EPA will continue to effectively perform its job responsibilities to ensure that our community remains safe,” he said.

Elected officials in the town of Cicero, some of whom took an active role in regulatory hearings about the Koppers plant in the 1980s, declined to comment. In an internal email obtained by the Independiente and MuckRock, Cicero town spokesperson Ray Hanania wrote, “i’m not going to respond to them .., if s [sic] major media does pick up the story i will point out we have no legal authority over koppers which is in stickney.”

In response to the Illinois EPA violations and this investigation, Koppers released a statement, saying it is “committed to making — and keeping — our surrounding communities safe places to live and work.”

The company, a subsidiary of a larger publicly-traded parent company, Koppers Holdings Inc., based in Pittsburgh and originally headquartered in Chicago, called its environmental safety efforts “robust;” pointed to performance investments of more than $200 million to its Stickney plant; and several projects “to further prevent incidents and enhance our environmental performance.”

Koppers reported more than $1 billion in revenue in 2022, according to its most recent earnings reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Koppers’ Stickney plant is the company’s single largest greenhouse gas emissions source, it has said in its annual reports, and it ranks as a global leader in producing several toxic chemicals used for producing tars and oils. At various points, the plant has produced as much as 17% of the American market for phthalic anhydride, 28% of its carbon pitch and 30% of its creosote.

“Our goal remains to prevent incidents, and when they happen, we self-report to the IEPA when we are required to do so under their regulations,” the statement reads. “We want our neighbors in and around Stickney to know that we have strong systems and safeguards in place that have been proven to be effective in reducing the impact on the resources we share.”

But community leaders say Koppers hasn’t done enough to address local concerns.

Delia Barajas, a member of the Cicero Community Farm, an environmental justice group, and a resident of Cicero for 32 years, said she first learned about Koppers in 2017 when she started doing research on her own. Barajas and other residents say they’re concerned that, unless they hound local and state regulators, they won’t know what’s being polluted in their community.

“They won’t inform you unless you start asking questions,” Barajas said. “It’s not like they knock on your door to tell you.”

‘I woke up one night trying to gasp for the air that was missing from my lungs’

Maria Esparza has lived in Cicero since 1987 and said she noticed the foul smells as soon as she moved into her home right off of 38th Street. Esparza and her neighbors live in a block of homes situated just a few hundred feet from Koppers and the other permitted industrial facilities lining Pershing Road. After a decade living there, she developed respiratory problems. The first time Esparza went to see a lung specialist, the doctor seemed surprised she didn’t smoke cigarettes or work in a factory.

“When the doctor looked at my lungs, he asked me if I worked in a pesticide factory,” Esparza said.

Naphthalene, one of the chemicals that Koppers emits the most of, is often used in pesticides. Of several hazardous pollutants that Koppers emits a steady stream of, naphthalene and another cancer-linked chemical, benzene, stand out from the others. Koppers emits more of these two pollutants than any other facility in Cook County.

Nationally, Koppers’ annual naphthalene emissions rank 19th out of more than 1,500 facilities, according to our analysis of the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory data. The polluters ahead of Koppers on this list include sugar manufacturing companies in Florida, aluminum processing plants outside of small towns in Kentucky and petrochemical plants in Texas and Louisiana. Koppers’ Stickney plant is now its sole North American refinery for naphthalene, following the closure and sale of its West Virginia plant, but it has been emitting the chemical since at least 1987, according to EPA records.

After seeking treatment for six months, Esparza said she seemed to be in the clear. She tried to take precautions, like keeping her windows and doors sealed shut to avoid chemicals from entering her home. But when her symptoms returned in 2018, Esparza said she experienced coughing fits that left her feeling like she was suffocating. Her daughter and primary caregiver, Connie Guzman, said it felt like a medical mystery.

“I woke up one night trying to gasp for the air that was missing from my lungs,” Esparza said.

Esparza’s respiratory problems can’t be traced back to any one form of pollution or polluter. For any resident of Cicero, sources of industrial pollution like Koppers mingle with the risks of breathing in soot and exhaust from cars and trucks, or even smoke from wildfires like the ones that blanketed the Midwest last summer.

Yanina Espinoza moved to Cicero in 1995 with her family, in a home just a few hundred yards from the Pershing Road factories. Her mother, Guillermina Ortega Sandoval de Espinoza, always stayed at home, never smoked and had never worked outside. But when she was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, pneumonia and cardiac insufficiency, which led to heart failure, her family said, a doctor described her lungs as resembling a ‘smoker’s lungs.’”

The Espinoza family said they considered moving from Cicero but decided against it. They were wary of Koppers and other plants nearby, but assumed it was safe enough to live there. But her mother’s symptoms worsened, her family said, and Guillermina Espinoza died in August at the age of 78.

“I know it’s highly unlikely that these companies will move somewhere else, so I hope that they at least take responsibility for their” [pollution], her daughter said.

Environmental health experts say that the mix of Koppers’ chemicals with other types of pollution, a process often called “cumulative impact,” is concerning. And when polluters go beyond what they’re allowed to release, as in the case of Koppers’ alleged violations, it’s hard to know just how much more dangerous the air is.

Several census tracts near Koppers have modeled cancer risks from the pollutant naphthalene that are about five times higher than the national average, according to an EPA assessment.

One census tract, reaching behind the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal into central Stickney, is the highest in the country. Even here, the associated cancer risk would not be considered “high risk” on its own, said Jun Wu, professor of environmental and occupational health at the University of California, Irvine.

Still, the level Koppers is allowed to pollute presents some risk. And if Koppers is polluting more than they self-report, as the state violations allege, the risk may be even higher still, according to Susan Buchanan, an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s School of Public Health.

“Having a violation is really bad. You can assume the levels that the Illinois EPA sets are not protective of everybody in the community — especially children and pregnant people and people with asthma and COPD,” Buchanan said.

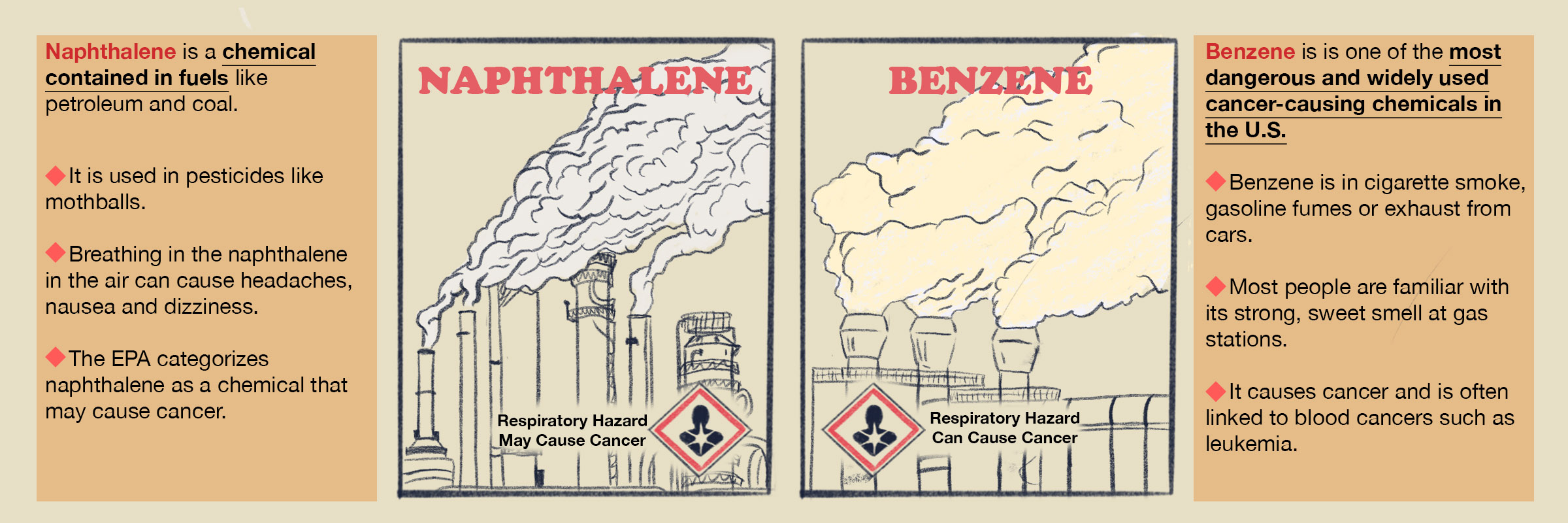

Naphthalene is a chemical contained in fuels like petroleum and coal. It is released when things like wood, tobacco or fossil fuels burn and can be found in cigarette smoke, car exhaust and smoke from forest fires. When inhaled as a gas, naphthalene enters the body where it is broken down to other chemicals that react with cells and damage tissues. This toxicity kills insects, which is why it’s used in pesticides like mothballs.

The EPA categorizes naphthalene as a chemical that possibly causes cancer. However, the state of California has classified naphthalene as a substance known to cause cancer since 2002.

Benzene, on the other hand, is one of the most widely used and dangerous carcinogens in the U.S. Many people are exposed to benzene through gasoline fumes and car exhaust. Recognizable by its sweet scent at gas stations, benzene is extensively researched, with links to leukemia and other blood cancers.

Some of the other pollutants that Koppers releases, like phthalic and maleic anhydride or sulfur and nitrogen oxides, are not carcinogens.These chemicals irritate humans’ airways and can trigger or worsen respiratory diseases like asthma. Koppers is one of a handful of Cook County’s leading polluters for each of these chemicals.

For phthalic and maleic anhydride, Koppers ranks second out of more than 100 facilities in the country that report these emissions to the EPA. The only facility that releases more is a chemical plant in Joliet, Illinois. That company, Stepan Co., settled with the state for $360,725 last year after the attorney general’s office filed a complaint related to the release of the dangerous chemical ethylene oxide. The case was based on a referral from the Illinois EPA.

When Esparza returned to the doctor in 2018, it took multiple X-rays and several pulmonologists to try and figure out what made her respiratory issues return 20 years later.

They eventually concluded that Esparza’s symptoms aligned with interstitial lung disease, an autoimmune disease in which lung tissue becomes scarred, typically as a result of long-term exposure to toxins.

Esparza’s scarring has since spread over most of her lungs. There is no treatment for the condition, only preventative medicine to deter the spreading. Because she cannot move out of Cicero, she said she is continuing to take her medication and praying the situation gets better.

‘Your Health is Safeguarded!’

Koppers and neighboring residents have battled over the air here for close to 50 years.

The Stickney plant, which is located next to one of the largest sewage treatment facilities in the nation, converts crude tar waste from steel production and petroleum refining into refined tars, chemical oils and creosote — a sticky, yellow liquid which is oftentimes used as a preservative to treat wood against termites, fungi and other pests.

When the coal plant opened a century ago, in 1922, the surrounding area had a few homes but was mostly prairie and grassland. Koppers marketed its coal products under the “Koppers Chicago Coke” brand and, in full-page newspaper advertisements, claimed that its heating coal was “clean,” even though its dangers had been known for centuries.

“Your Health is Safeguarded!” one ad from 1925 reads.

Starting in the 1960s, residents and nearby workers began complaining about the odors and health hazards of Koppers. In 1964, after the superintendent of the neighboring sanitation sewage facility said his employees were beginning to feel the effects of Koppers’ tar emissions, Stickney village leaders instructed their police chief to routinely check on the plant.

In 1969, Koppers expanded its plant to include facilities to process phthalic anhydride — used in glass fiber, plastics and paints — and became the sole or principal supplier for nearly a dozen companies in Illinois. But Cicero town officials were caught off-guard by the expansion, according to press accounts at the time, and Koppers assured local leaders that it would include air pollution measures.

“Though this plant will be in Stickney, we definitely want to see that all air pollution control systems will be of the best grade, so that this plant will not create a nuisance,” Michael Longo, the chief investigator of Cicero’s air pollution committee at the time, told the Berwyn Life newspaper.

But problems continued. In the fall of 1977, after solid flakes of phthalic anhydride were found on vehicles parked at nearby truck terminals, damaging their paint finishes, the state EPA accused Koppers of violating environmental pollution laws. (Koppers did not admit wrongdoing but did not refute the allegations; it later spent at least $1.3 million installing new safeguards.)

In 1985, a Ukrainian-born chemist named Peter Arendovich, who had struggled with bad and irritating odors from Koppers for years, began a quixotic, five-year campaign to stem the plant’s pollution. He and another resident, Patricia Listermann, lodged complaints with county and state regulators, convened a series of public meetings at nearby Morton College and the Koppers facility, sent out 18,000 health surveys to neighborhood residents and led two public hearings at Cicero Town Hall in 1989.

In 1990, the Illinois Pollution Control Board, an independent agency created two decades earlier to adjudicate non-criminal violations of the state’s main environmental law, initially ruled in the Cicero residents’ favor, by a narrow 4-to-3 vote. It found that Koppers had violated a core section of the law, which defines air pollution as anything that would “unreasonably interfere with the enjoyment of life or property,” and ordered them to prepare detailed plans to control the odors. Despite Koppers’ “significant social and economic value” to the community — at the time, millions of dollars a year in wages for some 200 employees, materials and local taxes and $6 million in annual profit — the plant had caused “continuing distress … to its citizen neighbors.”

Koppers appealed, saying its location was critical to the region’s economy, with access to the Sanitary and Ship Canal, the railway system and the interstate highway system — all vital in the transportation of raw materials and finished products. Months later, the state pollution board reversed its decision, finding that Koppers had spent $600,000 to implement air pollution and odor control measures. Still, it noted that the board’s order “does not preclude other enforcement actions being brought against Koppers if the violations continue.”

In response to questions for this story, the Illinois Pollution Control Board said it has no pending complaints about the Koppers plant and declined to comment on the facility’s environmental history.

Arendovich, the chemist, moved to Cicero in 1983. Shortly after his fight with Koppers ended, he moved away, to the village of Lemont. Now 86, he still owns two rental properties in Cicero near the plant.

In a phone interview, Arendovich described his yearslong regulatory battle with Koppers as a cat-and-mouse game: Neighbors would see smoke rise from its tanks and experience nausea and headaches. They would complain and Koppers would “always, kind of, blame someone else — ‘Oh, the smell is coming from the sewage facility.’ But once the sewage facility cleaned itself up, the odor was still there.”

After the Illinois pollution board’s ruling in 1990, Arendovich said residents largely forgot about Koppers’ legacy of industrial pollution. Because of a lack of air quality monitoring or information about the links of certain chemicals to respiratory issues and cancers, “no one thought about the health issues.”

“It was sort of taboo to talk about. This is a mostly blue-collar area, they are more tolerant to things,” he said. “They would say, ‘It’s just a smell.’ We thought the problem had been solved.”

After he moved away from Cicero, Arendovich said his constant asthma, which he attributed to ragweed or pets, dramatically improved. “I barely have that anymore,” he said.

The public fight did achieve some impact for residents and environmentalists. In 1990, the village of Stickney denied a permit for Koppers to build a one-story concrete-and-steel boiler to burn wastes, after significant community opposition. But there were more issues.

In 1993, a 22-year-old worker from Mokena, Robert Aftanas, died, and five others were hospitalized, when hydrogen sulfide gas was released during a routine maintenance operation. In 1995, 17,000 gallons of tar spilled from the facility into the shipping canal, resulting in a complicated cleanup. Koppers and the Illinois Attorney General’s Office settled both cases as part of a lawsuit filed by the agency, with the company paying a $40,000 fine. In 1998, the EPA fined the plant more than $335,000 for violations of the federal Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act.

In more recent years, Koppers has run afoul of several state and federal environmental laws. In 2006, the federal EPA mandated a $138,000 cleanup program for the hazardous chemical, ortho-xylene, and levied an $80,000 fine. A fire in 2020 partially shut down the plant and resulted in another, three-year environmental monitoring plan.

All the while, the Stickney plant results in huge profits for Koppers. Thirty-five years ago, in 1988, Koppers disclosed to the Illinois Pollution Control Board that the plant’s operations resulted in a net profit of $6 million that year, roughly $15.6 million in today’s dollars. In 2022, Koppers’ coal tar and chemical manufacturing segment, of which the Stickney plant is the only U.S. facility and one of just four worldwide, accounted for $612 million in revenue, up nearly 60% from two years earlier, according to SEC filings. The increase has mainly been driven by demand for plastics and vinyl in the housing construction and automotive industries.

Since 2014, Koppers has touted its commitment to the environment, as part of its “Zero Harm” initiative. In 2020, the company partnered with Argonne National Laboratory for a remediation project, using willows and grasses to improve the soil at a barge and rail shipping terminal at the Stickney Plant it leases. Koppers has also promoted its close community ties, including partnerships with Cicero’s elementary school system and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. (Cicero’s District 99 said it doesn’t have a record of any community partnership with Koppers and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

The company’s SEC filings paint a much bleaker environmental picture; At the end of 2022, the company reported substantial expenses related to cleaning up already-contaminated sites, including nearly $11 million in reserves for what it calls “environmental remediation” and $16 million in annual operating costs to control existing pollution. “Contamination has been identified and is being investigated and remediated at many of our sites by us or other parties,” Koppers’ latest annual report reads.

Koppers, along with a number of other companies, is also embroiled in two class-action lawsuits, in Pennsylvania and Tennessee, by dozens of people who said they suffered illnesses, including cancer, as a result of Koppers-made coal tar pitch. One plaintiff is seeking $15 million in damages. The company has also been named in an ongoing case involving the release of hazardous waste at the Portland Harbor Superfund site, at the Willamette River in Oregon.

Meanwhile, the coal tar that Koppers produces to coat driveways and parking lots has been found to contribute to a number of severe and life-altering illnesses, researchers have repeatedly found.

After a peer-reviewed study published in 2013 in the Environmental Science and Technology journal found that exposure to coal tar-contaminated dust during the first six years of life significantly increased the risk of developing cancer, Koppers went on the defensive. During an industry conference that year, a company health and safety official urged contractors in attendance to steer clear of the health impacts of their products and talk about their contributions to local economies, according to a Chicago Tribune investigation.

“To eliminate a useful product and put the businesses and jobs of real people at risk … hurts more people than it helps,” said the Koppers official, Mike Juba.

Cicero’s priorities: ‘Its businesses or its residents?’

For those that live in Cicero and similar fence-line communities, activists and lawmakers have been pushing a series of environmental justice reforms that would give communities more of a say about which industries can operate in their backyards.

In some important ways, Cicero resembles Southwest Chicago, which has been the focus of pitched battles over air pollution, said Brian Urbaszewski, the director of environmental health programs for the Respiratory Health Association. Chicago neighborhoods directly next to the eastern part of Cicero, where the Koppers plant is located, and to the south of the facility, rank among the worst for the city’s environmental justice index scale.

In Illinois last year, an environmental justice bill was introduced in the state legislature, which, among other things, would have allowed for community involvement in zoning and permitting for industrial facilities. For example, the bill would have given residents greater standing to challenge permitting decisions by the Illinois EPA. Despite having 17 co-sponsors, it failed in the Illinois House on a narrow 57-to-43 vote, with 60 votes needed to pass. Legislators blamed procedural errors for its demise.

“Passing state legislation would go a long way towards giving nearby residents power over the air they breathe going forward,” Urbaszewski said. “Full disclosure and transparency and letting people have a voice on huge sources of toxic emissions put right next to their homes and schools should not be controversial.”

City, state and federal regulators are also being asked to consider a company’s environmental record when considering whether to extend existing operating permits, said Kim Wasserman, executive director of Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, which successfully pushed to have the Crawford Power Plant closed in neighboring Little Village in 2012.

“For many frontline low-income communities of color, this is the reality, every day, in dealing with polluters,” said Wasserman, who called the Koppers violations a “disaster” for those living here.

In the short-term, Cicero’s residents are forced to navigate living in a densely-packed industrial corridor, with a busy railway, two Amazon warehouses and a dozen industrial polluters. The pollutants emitted from Koppers combine with other everyday pollutants, such as exhaust from cars and delivery trucks and tobacco smoke.

In most cases, it’s impossible to trace a single cancer diagnosis, or any chronic health condition, back to any one source.

“No level is protective against getting cancer,” said Buchanan of the University of Illinois at Chicago’s School of Public Health. “But you can say with confidence that people shouldn’t be exposed to more air carcinogens than people in another area, simply because of where they live.”

Koppers’ location on the border of two relatively small municipalities complicates the regulatory picture. But boundary lines aside, the plant is closer to, and one of the most prominent features of, Cicero, said Jojo Galva Mora, a curator at the Chicago History Museum who lived in Cicero and is now pursuing a doctorate in history at Northwestern University. And those who live and work here will likely have to reckon with a host of questions, he said.

“An ever-growing amount of warehouses outlines the northern end of town. The town’s western edge is bound mainly by the industrial corridor on Cicero Avenue,” Mora said. “What kind of message does that send to prospective residents, visitors, and those who pass through? Where are the town’s priorities? Its businesses or its residents?”

Support for this project came from the Data-Driven Reporting Project, which is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism; the Rita Allen Foundation; the Reva and David Logan Foundation; the Healthy Communities Foundation; and the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri.

Reporting and writing for “The Air We Breathe” by Dillon Bergin and Derek Kravitz of MuckRock, Stephana Ocneanu and Glendalys Valdes of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and Richie Requena for the Cicero Independiente. Data analysis by Dillon Bergin of MuckRock. Graphics and illustrations by Brian Herrera for the Cicero Independiente and MuckRock and Kelly Kauffman of MuckRock. Drone footage by Jesus J. Montero for the Cicero Independiente and editing by Kelly Kauffman of MuckRock. Editing by Derek Kravitz of MuckRock and April Alonso, Irene Romulo and Luis Velazquez of the Cicero Independiente. Sensor installation by Sanjin Ibrahimovic of MuckRock.