This article was originally published in SEJournal.

Requesting public records, or information and documents from the government, can seem like exactly the type of thing a freelancer shouldn’t spend time on. You may not know what to request or how. You may not get the documents.

And that’s just the start. If you do file a request, you may or may not have to bother a public information officer, it may or may not cost you, and in the end, you may or may not even have a story.

“Public records can take your reporting to places no other reporter has gone, shedding light on corners of your beat where the public has the right to know.”

But public records can take your reporting to places no other reporter has gone, shedding light on corners of your beat where the public has the right to know. And when you make claims about what happened in those dark corners, you can show your readers that you have the documents and data to prove it.

MuckRock, the organization I work for, can’t solve all the problems of chasing down public records, but our goal is to make it possible for both journalists and nonjournalists to spend less time on “may nots” and more time muckraking. Our aim is to create tools and guides that are especially useful to journalists who aren’t in big, well-resourced newsrooms.

Let’s dig into how you can make the most of our tools and community.

File a request or find inspiration

Before I worked at MuckRock, I was a Report for America corps member with Searchlight New Mexico. As I stumbled through my first public records requests at that job, I found MuckRock’s website.

My newsroom didn’t have an organizational account to file requests through MuckRock’s filing platform, but I quickly realized how valuable it is that thousands of others have.

Long before I ever filed a request on MuckRock, I spent hours combing through all the requests made public by other users. I found inspiration for requests in the beat I was working on and the language to ask for the right documents.

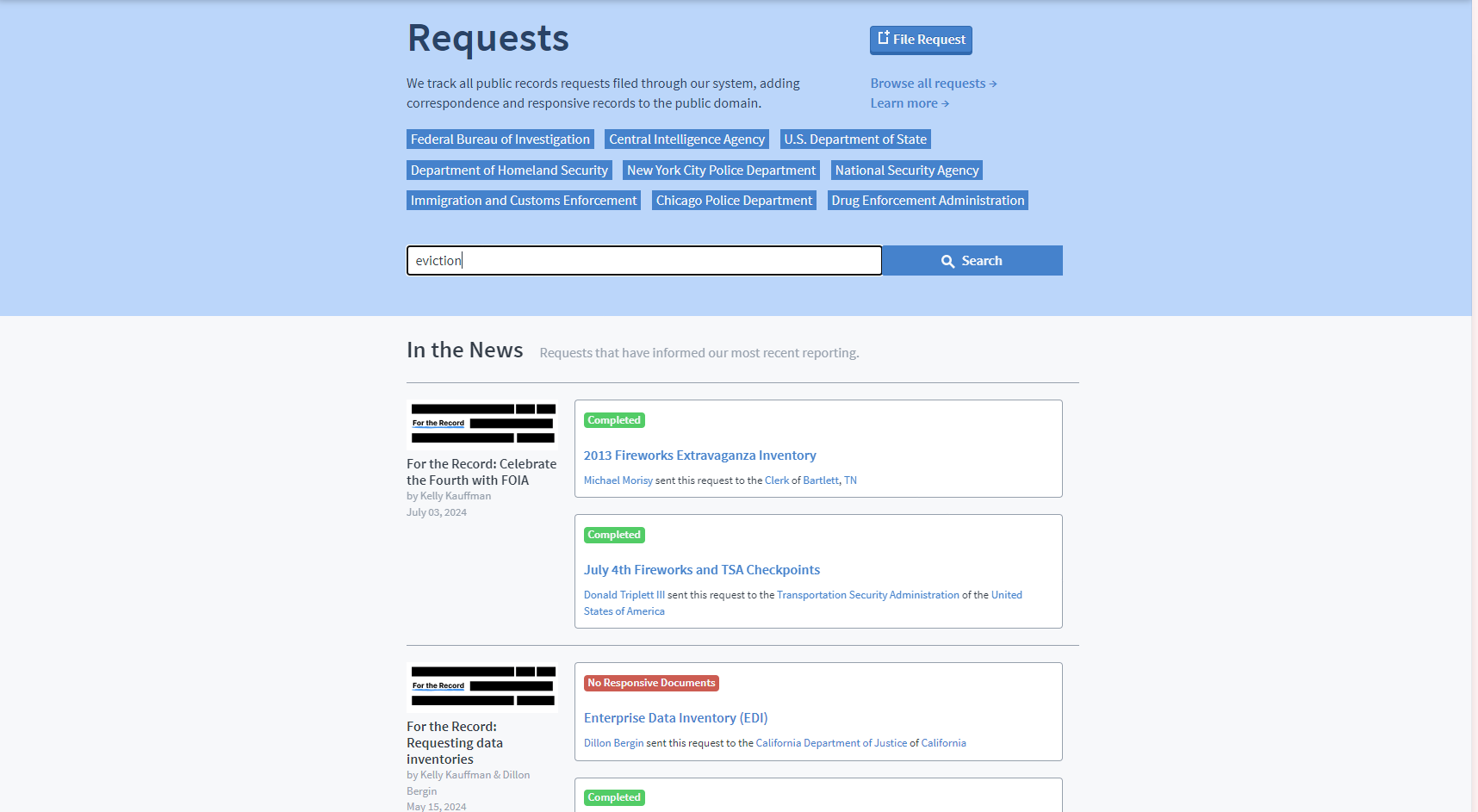

I searched phrases like “eviction” and “code violation,” as I grasped to find the right language to get the information I needed. I was investigating a tip our newsroom had received about apartment complexes violating the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and evicting tenants illegally.

That tip became public records requests, and those public records requests became an investigation and then an investigative series. Later, I wrote a reporting recipe for MuckRock, explaining how other reporters can find similar data and documents to investigate housing and evictions.

At the time I write this, there are almost 100,000 requests on MuckRock’s site that have been made public by users. This is where I tell most people to start using MuckRock. It’s free, and every day there are more requests on the site.

All you have to do is find a request you want to file, copy-and-paste the language for requests that you’re interested in and send them off in your own email to a public records officer. You can crib language for water quality complaints, air pollution inventory data, nuclear waste storage or hunting tickets.

Just head to the search bar of all requests and start brainstorming.

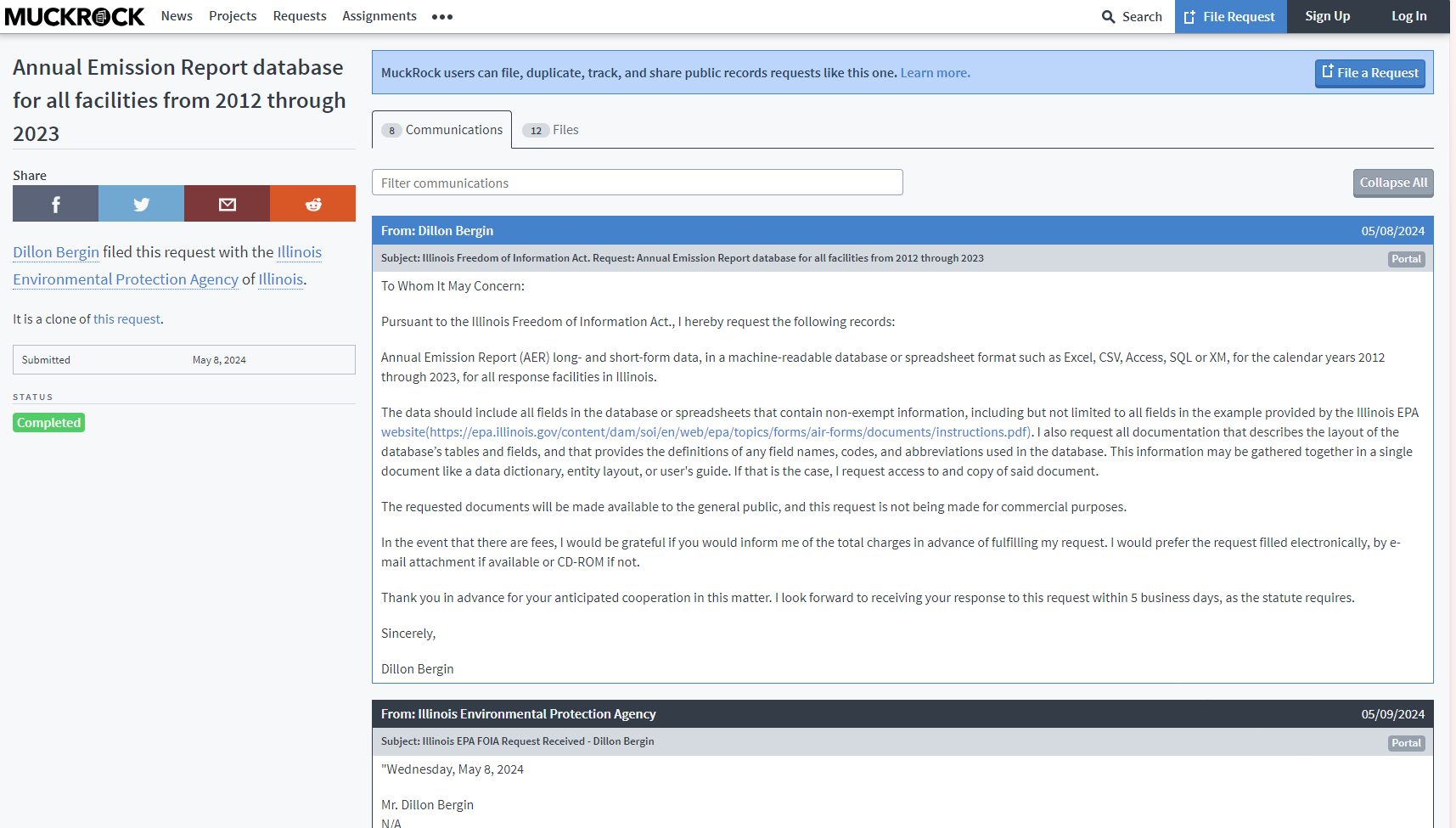

If you do have the money to pay to file requests through MuckRock, which costs about $5 a request, our filing platform makes the logistics of each request easier. The platform is essentially a feed of your requests to different agencies that brings all communications into one place.

Our small team of support staff works behind-the-scenes to smooth out the roadblocks along the way. This makes it easier for you to find the right person at an agency to file to, send letters through snail mail, bulk file requests to many agencies and share your requests with colleagues as you work.

Organize, analyze, even transcribe

Once you do get the documents you were looking for, you can store them, share them and analyze them in our platform DocumentCloud. DocumentCloud is completely free for journalists. All you have to do is make sure we verify that you are a journalist.

When you upload your documents to DocumentCloud, they’re automatically converted into searchable form, which makes it easy to hunt across your documents for keywords or phrases.

You can then tag documents if you want to organize them by topics. You can annotate and take notes as you read. You can reorganize the order of pages and flip those hard-to-read tables of government data to display vertically. And you can gather all your documents in a project that you keep private to share with colleagues, or make public to share with the world.

When you do share the documents with the world — so your readers can see the hard-earned details of your digging — you can redact parts of documents and embed them in your story.

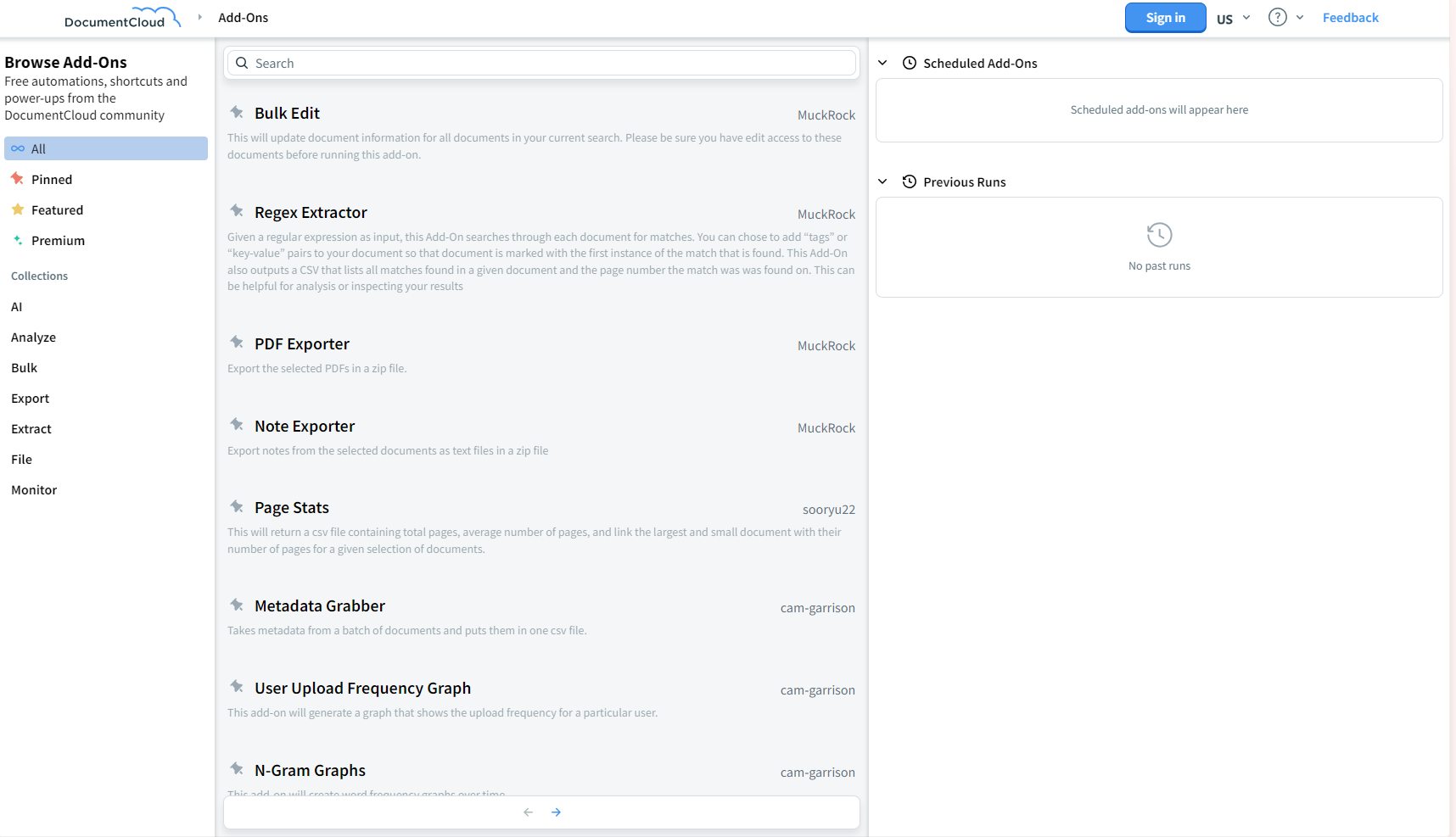

But here’s where things get even more fun: Those are just some of the basic functions of DocumentCloud. Over the last several years, DocumentCloud users have been building “Add-Ons” to fit even more specific needs. You can use an Add-On to scrape parts of a website, import annoying email file types or use AI to summarize your documents.

One of my favorite Add-Ons monitors changes to a website, which can be especially useful for government reports that are uploaded or changed often. I even use an Add-On to transcribe all my interviews now instead of relying on expensive and proprietary transcription software.

Join FOIA Friday conversations

There’s nothing like getting a USB drive in the mail, filled with public records, or downloading a zip file that you know has the information that you’ve been fighting for. The only thing that can make that moment even sweeter is running to a FOIA friend and basking in the victory together. Enter FOIA Fridays.

Earlier this year, I started a free monthly Zoom meeting called FOIA Friday as a way to gather people interested in talking through FOIA wins and challenges, tips and tricks. Each month, I lead the conversation with a presentation on a specific topic, like appeals, data inventories or whether nonprofits and businesses are subject to public records laws.

“The goal is to bring people together to learn, cheer each other on and generally nerd out.”

Sometimes I invite others who know more about a topic to come talk about it to the group. The goal is to bring people together to learn, cheer each other on and generally nerd out.

We also have a Slack channel — a free, collaborative discussion forum, which is a great place to workshop FOIA ideas and ask questions as well.

Tipsheets and weekly column

In addition to the tools and technology MuckRock makes, we produce our own original and collaborative journalism projects. MuckRock’s engagement journalist, Kelly Kauffman, also writes a weekly column, For the Record, about the latest battles, threats and victories in the world of FOIA, transparency and accountability.

We publish tipsheets and reporting recipes for our original work as well, like a series that I worked on about air quality and public records.

The reporting recipes in that series are the condensed knowledge and experiences from MuckRock and Cicero Independiente’s investigation into air pollution in Cicero, Illinois. The investigation uncovered how the town’s biggest source of industrial pollution, Koppers coal tar plant, has also routinely been found in violation of both state and federal environmental laws dating back 50 years.

Reporters followed the story as the plant disputed the most recent violations and held a secret meeting with a group of seven elected officials and employees of the nearby village of Stickney. This work recently won the McElheny Award for Local Science Journalism and the Society of Professional Journalists New America award.

You can use our tipsheets and reporting recipes to assist in your own investigations. For example, to kick-start reporting on air pollution in your community, try this simple series out:

-

Read the first tipsheet, which is about how your local government decides what types of pollution are allowed to be emitted by who. You can then copy my request for air pollution permits and tailor it to your county’s or state’s air permit tracking database.

-

Once you have a permitted polluter in your area that you’re interested in learning more about, read the second article of the series on accessing complaints, violations and fines. Using the language I did in a request for all “compliance correspondence” is a good way to start your request. These compliance documents will give you insight into the problems the facility may have and how your local government is dealing with it.

-

Then, take a look at the last guide on planning and environmental impact statements, which outlines the documents governments use to plan for air pollution.

The first two guides of this series should help you find out what’s happening, and the last guide should help you understand what should be happening. Being able to reveal the gap between the two, or what the government sets as its own standards and what is really happening, is the true power of public records-driven reporting.

We’re always striving to make our work more reproducible, so if you have any questions about reporting we’ve done, find us on Slack to ask a question!

To keep an eye out for all the new things in our work, sign up for our newsletter and stay in touch.