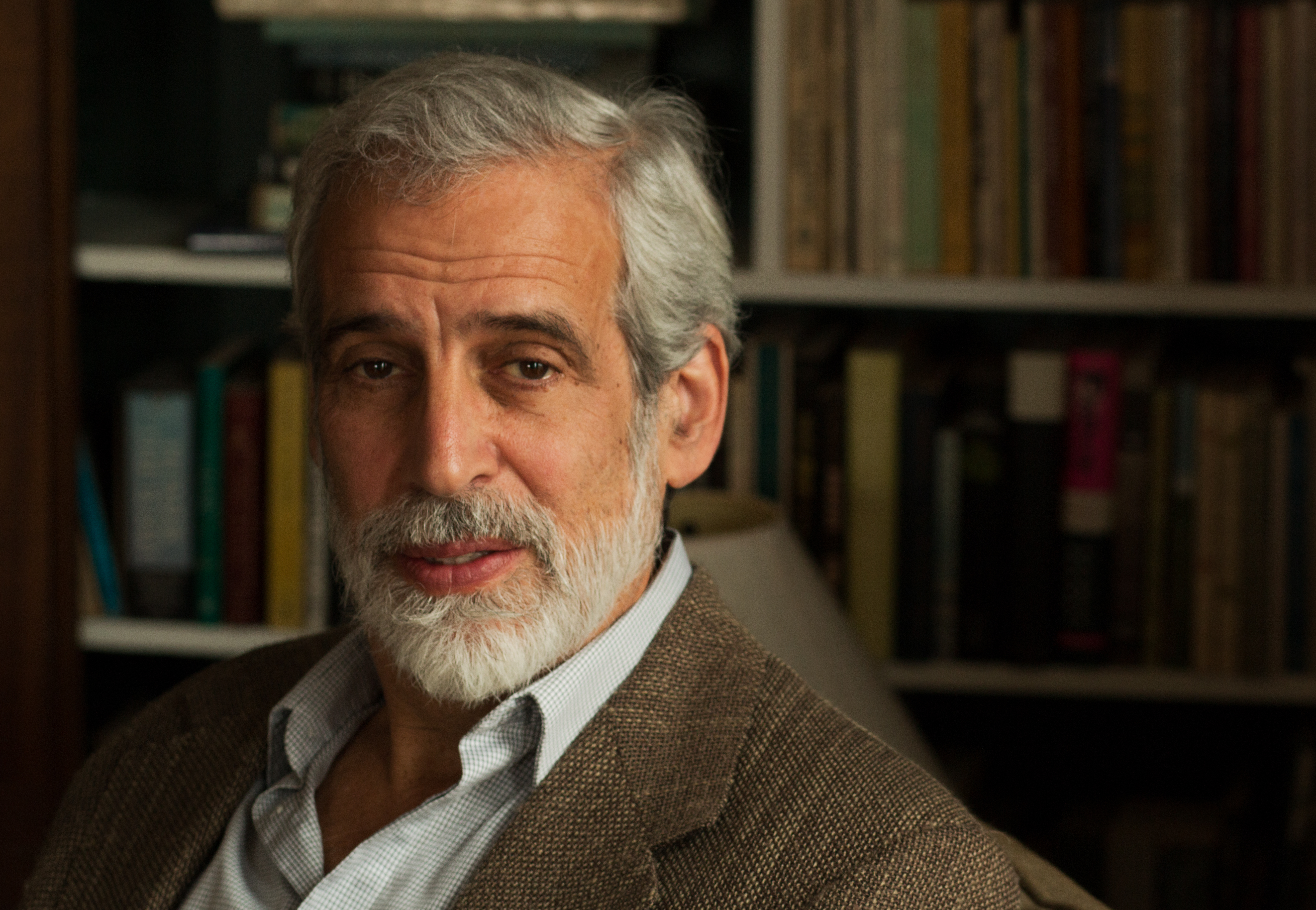

Jamie Kalven is the founder of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Invisible Institute, a nonprofit newsroom operating out of Chicago’s South Side. Kalven is a writer and human rights activist with extensive experience reporting on police misconduct in Chicago. Most recently, Kalven received an Academy Award nomination for his work on the film ‘Incident.’

In this conversation, we discuss Kalven’s landmark public records win in Kalven v. City of Chicago (2014), how AI can be used to analyze data received through FOIA and hopes for the future of the transparency landscape.

Would you tell me about your first FOIA request? Do you remember what you were looking for in your very first one?

Oh, I’ve been at it for so long. But it would have been probably in the early 2000s, and almost surely would have been in connection with some incident of police abuse in public housing. I was reporting from public housing, so I probably would have been seeking the CR, the investigation in a particular case.

Do you remember how FOIA as a toolset came into your knowledge? How did you become aware of FOIA?

That’s a pretty interesting story. I don’t know how much you know about my history, but I spent something on the order of 14 years immersed in high-rise public housing, Stateway Gardens in particular. I was an established writer at that point, and I was initially trying to facilitate access to that environment for other journalists. Ultimately, I got sick of the poor coverage, so we started a publication called The View from The Ground from a vacant unit at Stateway Gardens. The reporting focused more and more on individual instances of police abuse.

People would walk into my office having just been beaten up and bleeding. We had landlines then, I had a phone in the office and would urge them to call the oversight agency, which was the Office of Professional Standards. I would literally drag people over to file complaints and then follow the complaints. Over a period of several years, I did more and more of this kind of reporting on individual acts of abuse — particular blows from particular hands against particular bodies.

I was working with lawyers and law students from the U of C law school — we’ve worked together for 25 years — and they began to bring civil rights suits based on my reporting. The question formed: we’ve established through careful reporting the reality of these patterns of abuse, so how would the world have to be organized — what institutional conditions — to allow this? And so we began more aggressive FOIA practices, and also litigation.

I think there were in all maybe five or six federal civil rights suits that arose out of the reporting I was doing. The culminating case was Bond v. Utreras. You’re probably aware of it. It was a Monell suit. I don’t know if that term means anything to you?

No, what is a Monell suit?

So if a judge allows you to have a Monell suit, you can name supervisory personnel — the mayor, the police superintendent, the city itself — as co-defendants with the defendants who allegedly did the abuse. What that allows is that in pretrial discovery, you can ask for all sorts of things. So we named those supervisory figures with the argument that the accountability system was broken, they knew it was broken, they didn’t fix it, so they were liable for the abuse. That opened the door to make discovery requests, for example, ‘give us a list of officers with the most complaints against them’ in the last 10 years, the last five years, I can’t remember what the duration was.

So the Bond case came to the point of settlement, and a young lawyer at Loevy & Loevy had an idea: ‘what do you think would happen if you intervened on behalf of the public and ask the judge to lift the protective order on the grounds that this is public information that is being withheld from the public?’ And I’m always game. My staff once joked that we should have T-shirts that say ‘Go for it,’ which is what I always say.

It’s a good slogan!

So, we did it. We had a sympathetic judge who ruled in our favor, and then all hell broke loose. The city went crazy, they stayed her opinion and appealed to the Seventh Circuit. It then became a big front page story — a ‘what are they hiding?’ kind of story. Ultimately, after a couple of years, we lost in the Seventh Circuit in an intensely anti-press decision. They reversed the judge on the grounds that she should never have allowed me to intervene in the first place. But there was a footnote in that opinion that said, I can’t remember it exactly — I should probably memorize it — something to the effect that ‘nothing in our opinion should be construed to suggest that Kalven can’t pursue the same documents under Illinois FOIA.’

Had you thought of that as an option before?

No, we were invested first in the legal strategy of accessing the documents through discovery, and then anonymizing them and making them public, and then the intervention strategy. After losing the appeal, though, I’ve always joked, we drove a truck through that footnote. I had an all-star team of lawyers — Flint Taylor from People’s Law Office, Jon Loevy from Loevy & Loevy, Craig Futterman from the law school — and we took them up on the footnote and we ultimately won in the Illinois appellate court.

So that’s the creation myth of our FOIA practice, and everybody’s FOIA practice, because we won. And what the Kalven decision says is that, apart from reasonable redactions, which doesn’t include police officers’ names, all these documents are public information.

So we established a frontier of transparency. It’s a big deal, and I don’t think there’s another jurisdiction in the country that has the same level. And it really matters. People use it all the time.

But the thing that’s frustrating is FOIA. You know, we’ve established a principle: this is public information. But then you have the FOIA machinery standing between the public and the information. I’ve used the image that it’s as if we were all given library cards that allowed us to check out a certain number of these documents. When what we should do, and it’s completely within our power to do, especially now technologically, is we should just throw the doors of the library open, right? It should all be available online.

And the thing that’s so powerful about that is… we’ve had some experience with this, because we’ve gotten, through another process of litigation, we actually got four years’ worth of all CRs, which enables certain kinds of analysis, and now analysis which can be enhanced by AI, where you could find things in this huge mass of documents. You can find patterns that are not reflected in the top level information.

The former inspector general Joe Ferguson and I almost got to the finish line during the Lightfoot years with legislation we drafted that would have created a public repository. So that going forward, everything — you know, all the underlying CRs, the full investigations — would go into the repository, and then you would just, over time, on a prioritized basis, work backwards.

The cost in doing it looking backwards is redaction. That’s the cost, and they greatly inflate what such redaction would cost. You could do it very efficiently. So that’s the next frontier, but what’s so interesting about it is that it would involve no change in the law.

It would just involve them taking the step to do it?

Yeah, you just base it on the Kalven decision. But it would actually create new information, because of the things you can do with patterns. So imagine you’re looking at racist or misogynistic behavior by police officers, you could have tens of thousands of files, that you could readily search for keywords. So you could create new knowledge.

So has there been any more movement?

You know, we’ve talked some with people in the city council. I haven’t had the energy to push it. I hope to in the next year. The real problem is you’re always fighting rear guard actions against efforts to roll back transparency.

Just to give you an example, the film “Incident” is based on all of this body camera footage that we were able to access ultimately. The Fraternal Order of Police contract that was recently ratified includes a provision that would prohibit any camera footage post-incident; any interactions, between officers and supervisors, post-incident.

Well, that would prohibit 90% of what we were able to show in the film — all the concurrent interactions that were going on while the body’s lying on the ground. And it’s incredibly revealing because you’re seeing how the official narrative forms virtually the moment the body hits the ground.

So if that regulation survives legal challenge — it may not — it’s a huge rollback of transparency, and not just for people like us, but for the oversight agencies. It means COPA [the Civilian Office of Police Accountability] doesn’t have access to that footage.

Wow, really? And that’s been ratified?

It’s been ratified by the City Council. The attorney general of Illinois went to the judge overseeing the consent decree, and she has asked the city to clarify its policy. But it’s not altogether clear that there’ll be the leverage there to get rid of it, because, if you’ve read the consent decree, virtually every clause has the caveat ‘subject to the collective bargaining agreement.’ So, in theory, the union agreement trumps the consent decree. We’re looking for other ways to challenge it legally.

So you spoke a bit about this in terms of FOIA being like a library card, but not giving you full access. Are there other frustrations you have with FOIA?

Yeah, I mean, I think it’s a frustrating system for everybody. It’s like this contraption that doesn’t really work very well that just stands between the public and information that belongs to the public.

And I don’t want to malign individual FOIA officers, because often we’ve been able to build a relationship with individual officers. They’re so used to people yelling at them that if you’re nice to them, they’ll sometimes be genuinely cooperative, trying to be helpful.

“We’ve established a principle: this is public information. But then you have the FOIA machinery standing between the public and the information.”

But the overall ethos of FOIA is to begrudgingly give the public information, as opposed to a commitment to doing it. The proposal that Joe Ferguson and I worked up for a repository, part of our argument for it, was that transparency shouldn’t be just a reluctant concession to the public. It should be a principle of governance. It should be a principle of governance. This is what good government looks like. ‘We’re invested in this,’ as opposed to being forced to do it.

In terms of Brandon Smith’s win [in forcing the city to release the dashcam footage of Laquan McDonald], I know you’ve said in other articles you didn’t think that video was something that could be FOIA’d. Why not?

That was an interesting moment. We had won the Kalven decision. I had published on Laquan McDonald in early February 2015. Once I made known the existence of the video, every media entity in the world FOIA’d for it. And they were all rejected.

Did you also FOIA for it?

I didn’t. I had done my reporting on it, making its existence known, and I just assumed they wouldn’t give it to us. And that was the practice. When the city responded to FOIA requests by saying, ‘there’s an ongoing investigation and we’ll only give it to you once the investigation is concluded,’ that had been the universal practice. So every beat reporter on the police department and every investigative reporter just sort of took that as a given.

Were you surprised that [Rahm] Emanuel didn’t choose to release it sooner with all the pressure?

I mean, they had so many opportunities to. It’s a fascinating story, and there’s a movie, we won an Emmy for it, called Sixteen Shots, that was on Showtime and that tells this story. What happened is that the city, the mayor and the city as a whole, doubled down on a transparently false narrative.

One of the things I’ve said often about investigative reporting is that it’s really rare as an investigative reporter, in my experience, that you can definitively say what happened. So I can’t to this day definitively say what happened the night that Laquan McDonald was shot. What I can definitively, absolutely, unequivocally say, and demonstrate, is that what the city said happened couldn’t possibly be true.

So I did that reporting and demolished the city’s narrative. I had the autopsy, I had a civilian witness. I knew of the existence of the video. And after that reporting appeared, and at various intervals, as pressure built, the administration could have released the video, had a really lousy 48 hours or week, and come out the other side. But because they doubled down on what was a demonstrably false narrative, the pressure just kept building and building and building.

And when the video finally was released, it didn’t just impeach the official narrative with respect to Laquan McDonald. It’s like the whole machinery blew up. The entire machinery of maintaining an official narrative through the mayor’s office and the police just blew up.

So there were many missed opportunities, and then I think it became an object lesson for others, here and elsewhere, that in the age of transparency, you just can’t can’t get away with it.

You have a lot of very public, well known cases. Are there any FOIA victories that you are really proud of that people don’t know about?

You know, actually the film I mentioned, Incident, that was a really interesting one. Because my initial reporting was based on body camera and surveillance video that COPA released in accordance with the post-Laquan McDonald rules about releasing footage within 60 days. And in the course of that, looking at police reports, we found that there was video, that they had referenced in the police reports, that they hadn’t released.

There was a reference to a dash cam video that wasn’t released — and this became front page news — we pressed them for it. And when we got it, it was apparent that while the body camera footage just shows the perspective of the officers; the dash cam showed the shooter, Officer Halley, really aggressively stepping in. It’s a different perspective. If it had been available, it would have changed public perception of what happened.

So we did a big project: “Six Durations of a Split Second.” It was six short videos looking at this incident in six different timescales. From milliseconds (what goes on in somebody’s brain when they form an intention to shoot) to years (what’s the impact on the community). It’s really fascinating.

About three years after that project had been completed and had been presented, Matt Topic of Loevy & Loevy called and said that the FOIA litigation initiated the day after the incident had continued and the city had provided 20 hours of body camera footage of and surveillance footage of all the officers who were involved in the incident and in the aftermath. He said, ‘If you want it, I’ve got everything.’

This case is an example of a couple of things. One is how protracted the FOIA process can be, because initially COPA complied. But there were things that weren’t included, not because of cover-up, but because of poor stewardship of evidence. And then the litigation pried loose even more.

I think the other point we haven’t touched on is that both “Six Durations of a Split Second” and the film “Incident” illustrate the level of skill, rigor, and care that are required to make optimal use of transparency. To take all of these different visual sources and accurately synchronize them to create a larger picture, it’s really intense work.

And I think these two projects establish a gold standard of what can be done, but it took great practitioners, I’m not talking about myself, but about my filmmaking collaborators.

So the upshot is that there’s this vast archive of information that’s being continuously uploaded from body cameras. If we could look at it, if we had the means to analyze this vast amount of data, which we could potentially do through AI, it could transform policing. There is this vast archive of body camera footage that nobody actually looks at unless there’s a “heater” case. It could be revelatory.

And not just about problematic patterns of policing. It could also teach us what good policing looks like. I mean, at any given time, there are a vast number of interactions between police and citizens going on in a city like this, some of which are exemplary. We never get to see those, either.

Everybody — including police departments — has been sort of daunted by the storage issues and the scale. And very few jurisdictions are really using body cameras in good faith in the sense of really trying to learn everything that can be learned. But imagine if they were?

So, I think if there has been a theme for our conversation, it’s the ‘frontiers of transparency.’ There are things that are within our power to do, and would not require any dramatic changes in existing law, but they would take political will.

I’ll just ask you one more thing. I’d like to know, in terms of your work with the CPDP project and the National Police Index, do you feel like those are well positioned to transform the FOIA or public records landscape?

You know, I had two goals in advancing the CPDP agenda. One was to create a useful tool for journalists, for civil rights lawyers, for public defenders, for the general public, and so on. That was central. But it was also to build out a demonstration project of what could be done with this information, if there was a will to do it.

So my attitude, and it continues to be the case at the Invisible Institute, has been instead of clamoring for government to do something — for example,‘you should create a public facing database’ — our theory of change has been to use civil society energies and resources to demonstrate what government should be doing and to encourage government adoption.

I think there’s no question that we, through CPDP, affected the practices of the OIG, the police department, the COPA, by means of this demonstration project. And when post-Laquan McDonald, the Department of Justice came in, they relied on our data.

But I think the element that is sometimes lost on people is that we’re a relatively small nonprofit — and can’t be the stewards of this information in perpetuity. Government should be doing that, but we’re making an argument for that through the rhetoric of action.

That’s great. I think that’s a great place to end. Thank you.